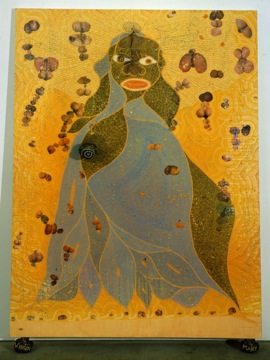

Chris Ofili, Holy Virgin Mary (1996)

I started thinking about the word “difficulty” in relation to controversial art because the things in art which grab me, even shock me, rarely line up with the scandal that art produces. The first time I saw Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, I was shocked by its color-saturated beauty and then totally freaked out by the beaver shot-butterflies, which I only understood as porn clippings when I was within a couple feet of the canvas. It’s a chilling and eloquent visual comment on colonial desire—on the art world’s hope of “discovering some new form of Hottentot” (in the words of Rebecca Harding Davis).

Controversial art often challenges the production and regulation of pleasure in museums and galleries. We are taught to expect very specific forms of pleasure from visual art. And the range of feeling allowed the spectator in the museum seems much narrower than that which we enjoy in other spaces. Artworks can be difficult in their affective intensity—in other words, when they describe and provoke “bad feelings” like sadness, anger, or anxiety.

Why are we prepared to accept the value of “feeling bad” when we read a novel, but not when we go to our museums? Why is it “easier” for us to watch an upsetting movie than it is to keep company with contemporary art that makes similar emotional demands on us?

Images from movies The Road (1996) and Dancer in the Dark (2000)

When I read Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006)—an almost unbearably difficult story about a post apocalyptic nightmare in which refugees wander a barren planet, surrounded by starvation, rape, and cannibalism—I felt like someone had ripped out a piece of my soul. Typical for the author, its flatly narrated portrait of a world of extreme violence is also a deeply sexist novel in which women figure as dead weight and/or emptied-out symbols of salvation. McCarthy won The Pulitzer Prize, Oprah selected the book for her book club, and it has been turned into a film (due for release next year). As readers and as filmgoers we are, apparently, eager to suffer.

Contemporary art presenting its audiences with challenging, urgent but far less cruel images, on the other hand, tends to provoke moral outrage—even when it asks far less of us as people (try contrasting the reaction to Ofili’s painting or Ron Athey’s or Karen Finley’s performances with the celebration of McCarthy’s novel). Think about it: it takes days to read a novel, and a feature length film like Lars Von Trier’s depressing Dancer in the Dark (2000) demands far more from its audience than does looking at a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe, or watching a performance by Franko B. And yet people have reacted to work by these artists as if it represented the absolute limit of the tolerable. Making matters worse, institutions struggle to find solid ground on which they might argue for the necessity of difficult images, difficult performance—of the value of unpleasurable experience in visual art.

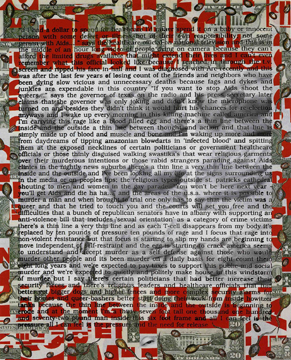

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Hujar Dead) (1988-89)

David Wojnarowicz’s work is difficult in this way—in its emotional intensity and in the demands it makes of us (like Athey, he was at the subject of a major censorship fight in the 1990s). I’d put his work, in fact, right up there with McCarthy’s novel in terms of its urgency and its power. His images can be formally complicated and demanding in terms of the time and attention they require from the viewer. Untitled (Hujar Dead) (1988-89), his posthumous portrait of Peter Hujar, is built around images snapped by his camera moments after Hujar died from AIDS. Layered over these images is a rant lifted from Wojnarowicz’s writing, describing his fury at public indifference to the AIDS crisis (you can read it and listen to him read other words here).

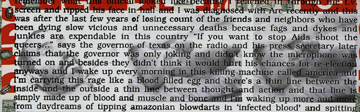

Detail of Untitled (Hujar Dead) (1988-89)

I’ll never forget seeing it for the first time. I was nailed to the floor and nearly in tears by the time I finished reading the writing that covers the work’s entire surface. It’s a difficult work in nearly every sense: it is emotional, the photographic images are of Hujar’s still warm corpse and if you read the text, you are in essence also looking over his body. It is hard to read, hard to describe, and it leaves you feeling drained, exhausted. And yet the work is incredibly alive, animated. It has the power to transform its viewer. Or at least to leave the viewer feeling challenged.

But many people don’t want to look at work like this, because they want art to make them “feel good.” They want to feel peaceful, satisfied, and smart. The commercial imperative of gallery spaces has trained us to prefer works that put us in the mood to consume—to buy a poster or a card. This work is clearly not going to do that.

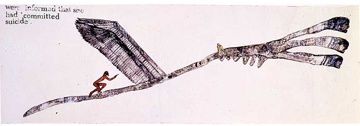

Nancy Spero, Torture of Women (1976)

Untitled (Hujar Dead) reminds me of Nancy Spero‘s Torture of Women (1976) or Carrie Mae Weems’s series, From Here I Saw What Happened…I Cried. They are visual manifestos, made in protest, outrage, and despair. You only “get it” if you meet the demands it makes of you as a spectator, and are willing keeping company with pain. This is not art about the institutions of art. This is art about something else. This art imagines itself as an agent in the world, capable of acting in the world.

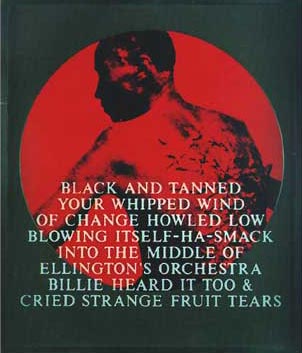

Carrie Mae Weems, from the series From Here I Saw What Happened…and I Cried (1995-1996)

We marvel at the beautiful. But we can also marvel at the fact that throughout history, in the face of the truly awful weight of violence and oppression—in the midst of war and the most intimate and frightening forms of persecution—poets and painters have turned to their craft to show the world as it is, in the attempt to make the world into something else.

Jennifer Doyle is the author of Sex Objects: Art and the Dialectics of Desire (Minnesota, 2006), and is an Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Riverside. She is currently finishing Critical Limits, a book about difficulty and emotion in contemporary art. She blogs about the cultural politics of soccer at From A Left Wing.

Pingback: Reflection in the Porcelain Pond | Art21 Blog