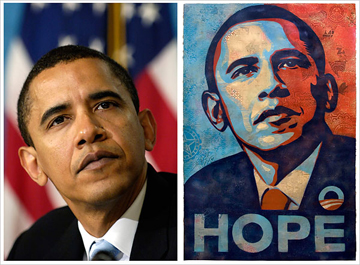

Not at all surprisingly for a corporate entity, the Associated Press recently established ownership of a photograph of Barack Obama taken at a 2006 National Press Club event by photographer Mannie Garcia. After some extensive sleuthing, the Garcia photograph was identified as the source for Shepard Fairey’s Hope image that we all have grown to know and love. That image has, in turn, gone into the world to flank numerous buttons, hats, t-shirts, stickers and countless other presidential tchotchkes.

L: Mannie Garcia/AP, 2006. R: Shepard Fairey, c. 2008. Via www.nytimes.com

In a wise and pretty gutsy move, Fairey preemptively sued the AP, claiming that he cannot be accused of copyright infringement and that his image is protected under fair-use copyright statutes. Money is at issue here too, though I can’t imagine Fairey made significant, if any, profit from the image. The same cannot be said for his Saks Fifth Avenue spring season marketing commission that borrows from early- to mid-20th-century propaganda-style imagery. No shade…

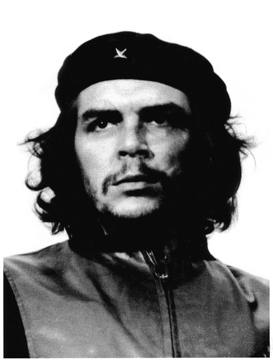

This whole scenario recalls the Alberto Korda photograph of Che Guevara that too went on to have a more successful life as a high-contrast graphic (yes, I had it on a t-shirt also; black image on a red background, of course).

Alberto Korda, Ernersto “Che” Guevara at the La Coubre memorial service, March 5, 1960.

Like Garcia’s photo, Korda’s image was taken while he was in the employ of a news service, which pretty much denies the photographer of any significant credit or direct financial benefits aside from the occasional lawsuit. What irony, considering Korda’s image ended up on the Cuban 3-peso note, but it also points toward the fact that legal courts are about the most effective option artists may have for financial remuneration for the lifetime of their artworks. Garcia, in a further twist, is claiming that the photo copyright is his and not the AP’s and that any credit or money should come to him. In the meantime, the AP wants credit and a cut of the profit from any subsequent use of Fairey’s image.

Um, I’m going to wager that no one from the AP has been on Harlem’s 125th street lately. Obama, unlike the litigants, has prudently distanced himself from the micro-economy that has sprung up around images of himself, his family, and that Fairey image. For instance, I ran into this guy in DC working the inaugural crowds and I normally see him in Harlem doing much of the same.

Harlem vendor in D.C.

Now that the president has become an icon, his image is, and has been, a boon for petit entrepreneurs in Harlem, and I’m sure any other site for a thriving street market where standards of “original” and “bootleg” are rarely considered. I wish the lawyers luck in tracking down all the subsequent profitable uses of the Fairey image.

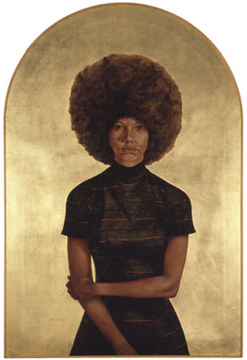

Lately I’ve been thinking through this question of icons and iconography through the work of Barkley Hendricks, who has been committing stylish black subjects to canvas since the 1960s. Full disclosure: Hendricks is currently on view at The Studio Museum in Harlem so this could be a backhanded, though legitimate, plug for our exhibition. But if you look at something for several months, you can’t help but think about it.

Barkley L. Hendricks, "Lawdy Mama," 1969, oil and gold leaf on linen canvas, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; gift of Stuart Liebman, in memory of Joseph B. Liebman 83.25

Hendricks understood the power of an attractive subject in a decontextualized and monochromatic setting, not just as an aesthetic tool but also perhaps as a way to preemptively disrupt any number of assumptions viewers may want to apply to his urban subjects. Many of Hendrick’s subjects were captured first in a photograph before being painted (Hendricks never travels without his camera) and in his cropping choices, one can see nods toward photography in the paintings.

I think a lot about Richard Avedon’s work when looking at Hendrick’s canvases. But mostly I think about Warhol and his understanding of what the photograph does as a documentary device and what the idiom of painting further does for the photographed subject even, or maybe especially, in an age of mechanical reproduction. All the accoutrements that traditionally accompanied a subject in traditional portraiture are evacuated in a Pop portrait and the sitter is simply adorned with celebrity, the icon equivalent for the Pop age. And apparently still, as Che Guevara and Obama exist more as celebrities in their most popular image incarnations than anything else.

I am of the mind that maybe a Modernist project may tell us more about image proliferation than anything that’s been produced since.

Marcel Duchamp, "L.H.O.O.Q.," 1919. Ink on found postcard

No one is a real icon until someone draws a moustache on your readymade likeness.