Danish art group SUPERFLEX has been exacerbating the art world for over a decade with its irreverent style of questioning, which hits hard at the foundations of the West’s economic system. But unlike traditional critiques of economics that are rooted in 19th- or 20th-century ideology, SUPERFLEX is able to generate seemingly new explorations into our economic dysfunction with projects that delve deep into our contemporary consciousness and our evolving relationship with copyright, environmentalism, global consumerism, and the Internet.

Left: photo of SUPERFLEX by Nikolai Howalt (Courtesy the Artists). Right: my Skype conversation with Bjørnstjerne Christiansen

I caught up with Bjøernstjerne Christiansen, one third of the Danish art trio, over Skype (he was in São Paulo, Brazil) to discuss the group’s work and his own thoughts about the latest failures of our global economic system. This transcript has been edited with the permission of the artist.

Hrag Vartanian: Were you surprised by the recent economic crisis?

Bjøernstjerne Christiansen: No, that’s the nature of economic systems. There is always someone thinking that he or she can develop a perfect system but it never works. Systems are doomed to collapse and restart in other ways and forms. It is interesting for us to examine and challenge the systems; that’s part of our work.

Flooded McDonald’s from SUPERFLEX on Vimeo.

HV: Can you tell me about your Flooded McDonald’s film, where you recreated the interior of a McDonald’s fast food restaurant and videotaped it being flooded? I noticed that it went viral on the web. I also felt that it comments on the economic meltdown.

BC: The film is open to interpretation, so we don’t want to point to McDonald’s as evil or anything too obvious, but it very much has to do with mass consumerism and the responsibility to deal with that. We wanted to make a film that would have several outputs and interpretations. We chose McDonald’s because it is one of the major brands of globalism. Even if people never go to McDonald’s, they know how it looks, smells and works. We made a replica of a classical McDonald’s, and the associations people have with that are important.

One can go into many interpretations about this…when things go wrong or too high-speed in our global economy, where is the personal responsibility? Also, it touches on the environmental disaster that mass consumerism creates. The strange thing is that recently in Europe, McDonald’s announced it will hire 15,000 new employees; it doesn’t seem much effected by the downturn.

HV: Is the Flooded McDonald’s the first SUPERFLEX project to go viral?

BC: No, the Free Beer project went viral. It is an open-source beer; it is free in the sense of freedom, not in the sense of “free beer.” We published the recipe and branding elements of Free Beer under a Creative Commons license (attribution: ShareAlike 2.5), which means anyone can use the recipe to brew their own and make money from it, but they have to publish their changes or improvements for others to benefit from their work. It has to do with intellectual property rights and how an idea or system from one context can be applied to another via this change—normal patterns of, in this case, production and innovation. When Free Beer was created, it was on the front pages of the New York Times, BBC, etc.

Free Beer is about the battle over the system of rights. This is particularly important since it impacts the issue of people taking our rights. We look at the copyright system, the patent system, and we try to challenge all those systems because they have become too much part of our society. When someone has an idea, their first reaction is to run to the patent office and trademark the name or idea and 200 variations of it so that others have difficulty working on something similar. People haven’t been challenging this system much and we think it is a dangerous thing. We are locked into this and people aren’t thinking critically about what that means and what the consequences are.

HV: How does that viral aspect impact your work? Do you plan for it now? Does it impact the production of the work?

BC: If you are the kind of artists we are, then you have the ambition that your art is going to be discussed. You don’t have to be a populist, but you are aware of the power of global media and how issues are going to be discussed. You become aware of how to talk about it. So when you send out a press release, you talk in a different way with the media than with an art gallery crowd.

You don’t have to be political but engaged, and as an individual, you should have an interest in how our society is developing. If you have something to say, then you try to get it out there.

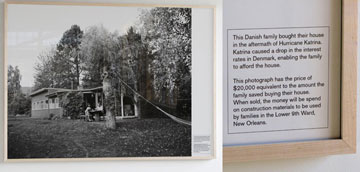

HV: I had some questions about the SUPERFLEX piece created for Prospect.1 in New Orleans, When The Levees Broke We Bought Our House (2008), which includes the description that, “this Danish family bought their house in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Katrina caused a drop in the interest rates in Denmark, enabling the family to afford the house.” That confused me and everyone I talked to was equally confused about the connection between Danish mortgage rates and Hurricane Katrina. It doesn’t sound like there’s a correlation. Can you explain that?

BC: The reason we made that work is so that the person who lives in NOLA and has that experience of his or her own personal economy should learn about the global factors involved. We wanted to highlight how the system is connected. We wanted to show that friends of ours, when they went to the bank, were directly told by the banker that there was a connection. We have been discussing this with banking and financial people and we are told that there are common economic issues involved. It might feel strange for someone outside that sector, but these variables impact other things in amazing ways that aren’t always obvious.

One thing about this project was that it was difficult to explain how to show this impact. We could have shown the financial papers explaining the situation, but we decided on creating a space in front of the photograph on display to give the feeling of volume. A typical house in New Orleans could be built by buying construction material equivalent to the amount the Danish family saved.

SUPERFLEX, "Free Shop," 2003-2008. Courtesy the Artists.

HV: Now your Free Shop project is very challenging, in that it removes the monetary aspect of commercial exchange from the equation by surprising people with a bill for their purchases that always equals zero. Can you tell me about that?

BC: Again, it has to do with that the fact that we are so impacted by systems which are imposed on us. It explores the exchange of value. We want people to explore the value of exchange. It is so part of the structure of our daily lives that we believe in them blindly. Free Shop was a way to challenge that. In stores, the cashier would tally things up and then look at you and say, “the total is zero.” In a way, your world collapses. What is surprising is that very few people went back and took more, even though they could.

The action takes places randomly and in different time intervals, so no one knows when it is in effect. So far it has been happening in six countries, including Japan and Poland. We also did it in a pharmacy which connects the artwork with the issue of pharmaceuticals, regulation, and pricing.

In Auckland, New Zealand, we are staging Today We Don’t Use the Word Dollars (2009) in a bank and it is part of New Zealand’s One Day Sculpture project (www.onedaysculpture.org.nz). Bank employees will not be able to use the word “money” in any written or spoken way with customers or amongst themselves. It is about challenging a system banks are very accustomed to. This has been a project that we’ve wanted to do for two years so it’s not a reaction to the current economic crisis.

HV: How has the current economic crisis given you insight?

BC: On many different levels in Denmark we had a “consumption machine”…meaning private consumerism exploded—a 150,000 Kroner apartment was all of a sudden worth 2 million. People were taking out loans, but we all knew that it was fake money. But no one wanted to stop the train and face the reality, so society played along blindly. So what inspired people was this speculative machine, but it turned out to be very dangerous. I think ideas have a great value because they comment on the economic system. I think many of our ideas in the next few years will challenge this system and the nature of it.

HV: Can you tell me about the aesthetics involved in SUPERFLEX’s work? Jeff Koons, for instance, is known for his shiny surfaces; SUPERFLEX is known for a extremely clean, simple format that uses Helvetica. Why?

BC: We’re slowly changing and challenging that. At first, we wanted to create a simple visual identity and structure to do that. We wanted to create a minimal tool and means of aesthetics. But later on, like in the McDonald’s project, it is starting to be challenged on our side. We now try not to have too fixed of an identity to realize a visualization of our project. Currently, we are trying to allow the nature of the idea to decide that.

HV: So, why Helvetica for instance?

BC: It is a visually strong font. It is easy to read and understand. We have done poster projects in the urban scape, and it works very well. But a graphic designer we work with has changed it, so now we have our own font that is related but different from the original font. Also, there is a beauty in Helvetica.

HV: While we are talking about the recent economic crisis in a larger abstract way, there is a very personal side to economics, isn’t there? So I wanted to ask you if the economic crisis has taught you anything about yourself.

BC: Not so much. Because we have always had a playful relationship with the economic system (which I mean in the best way), we have always considered the system very delicate and fragile. And if you create work in our way and the types of artists we are, anticipating ups and downs, we can deal with the modulations. It may be harder for people who are used to a steady life since they may react to change with greater difficulty.

Pingback: Economic Sur-realities: My Conversation with Bjøernstjerne Christiansen of SUPERFLEX (via Art21) — Hrag Vartanian

Pingback: Reader: June 4, 2009 « updownacross

Pingback: hawktraining » Blog Archive » links for 2009-07-05

Pingback: SFMOMA | OPEN SPACE » Blog Archive » Trip Without A Ticket: Free Store Variations

Pingback: Who’s Keeping SKOR? | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Recap: Creative Time Summit, Saturday October 9th, 2010 | Art21 Blog

Pingback: 5 Questions with Temporary Services | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Superflex, Copenhagen Based Art Group, Playfully Scrutinise Society in New Exhibition - Ours Magazine