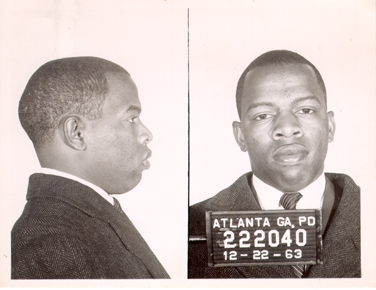

John Lewis. Courtesy High Museum of Art.

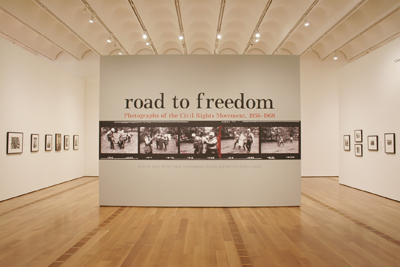

Like many museums, traveling shows tend to dominate the exhibition schedule at the High Museum of Art. In contrast, Road to Freedom: Photographs from the Civil Rights Movement, 1956-1968, organized by Julian Cox, Curator of Photography, was generated by the museum and drew on wide-ranging regional resources and exchange with the local community. The exhibition ran from June 7 to October 5, 2008, marking four decades since the assassination of Atlanta native Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Civil rights veteran and longtime U.S. Congressman for the 5th District in Atlanta, John Lewis contributed an afterward to the exhibition catalogue and was involved in education and outreach events at the museum. While working for the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC, or “snick”) in the 1960s, Lewis shared an Atlanta apartment with photographer Danny Lyon, who at the time was a staff photographer for the SNCC. Along with well-known photographers such as Lyon, Road to Freedom exhibited many photographers and photographs lost to history, including photojournalists working for the black press, and in some cases, evidence photos filed away decades ago.

Prior to his appointment at the High in 2005, Cox was an associate curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and also worked at the National Museum of Photography, Film, & Television in Bradford, England, and the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth. Michael David Murphy, subject of my last interview and co-organizer of Atlanta Celebrates Photography, notes, “Julian Cox’s impact on Atlanta’s cultural scene, and on the photography community specifically, cannot be underestimated. I’ve never seen a curator who’s more engaged with the public. Road to Freedom wasn’t just a remarkable feat of curation and scholarship, it was a generous gift to the city.”

"Road to Freedom" installation detail. Courtesy High Museum of Art.

Victoria Lichtendorf: It seems astonishing that Road to Freedom is the first major exhibition of Civil Rights photography in close to thirty years. How do you account for this lapse?

Julian Cox: I think it comes down to the fact that photojournalism and documentary photography do not have much of a home in fine art museums. If you look around the country, there are only a few institutions committed to showing this kind of work. The High wanted to appropriately mark the fortieth anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination; he’s an international figure, of course, but he’s also a great Atlantan, so again, we were trying to reach different audiences in putting together a show of this kind.

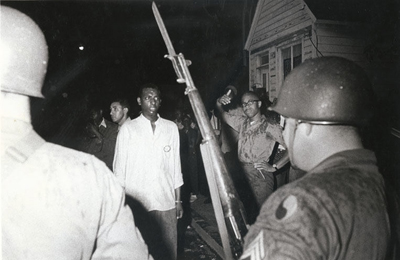

Danny Lyon (American, born 1942), "Stokely Carmichael, Confrontation with National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland," 1964. Gelatin silver print. Purchase with funds from Joan N. Whitcomb. Courtesy High Museum of Art.

VL: In a talk you gave for the 2007 ARLIS conference in Atlanta, you mentioned that as a relative newcomer to the States, you initially knew little about the Civil Rights Movement. In what ways did your “outsider” status act as an asset?

JC: In an odd way, I think it helped. People wanted to know what I was up to! I always made it clear that I was on a steep learning curve in terms of learning about the history and developing a nuanced view of the cultural implications etc…. I also made a point of stressing the focus of my inquiry as being about the photography and media culture of the period. I am a photography curator and historian after all.

VL: The exhibition stemmed not only from a desire to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of MLK’s assassination but also to expand the High’s photography collection. Thus in a very concrete sense, RTF seems to have had a lasting impact on the Museum. After the show has completed its tour, will there be any special efforts made to make the photographs accessible to the community on an ongoing basis?

JC: We are looking into the possibility of sharing parts of the archive/collection with colleague institutions in Georgia (Savannah, Columbus, Albany), and we also hope to have a presence at the Center for Civil and Human Rights Partnership, which will open in downtown Atlanta in 2011. We are also in dialogue with the Woodruff library at Emory University, which has some very significant manuscript collections that dovetail with the one we’ve assembled here.

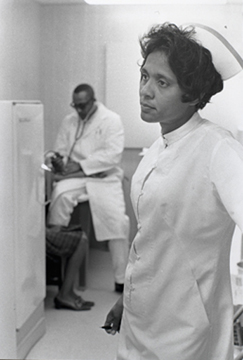

Doris Derby (American, born 1939), "Nurse and Doctor, Health Clinic in the Mississippi Delta," 1968. Gelatin silver print. Purchase with funds from Jeff and Valerie Levy. Courtesy High Museum of Art.

VL: The anniversary of King’s death and the subject of the exhibition were made that much more salient by the coinciding election. After opening in Atlanta on the heels of the contested and historic primary season, the show reopened November 8 at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, with whom you collaborated on the exhibition. Was this uncanny coincidence or well-planned timing? Do you know how the show has been received in D.C.?

JC: A little bit of both! The show was very well-received by the public in DC. More than 50,000 people saw it the week of President Obama’s inauguration.

VL: It seems you devoted a great deal of time and energy engaging with a broad spectrum of people involved with the movement, including photographers, journalists, activists, and scholars. Did your research methodology differ from your past curatorial endeavors, and if so, has it in any way changed your approach to current projects?

JC: I think the most interesting and exciting element in the project was the melding of oral history and history as traditionally written via documents, papers and primary sources. I found that fascinating, and something that I would like to try and implement in future projects, where applicable and relevant.

Lonnie J. Wilson, "Birmingham (Policeman with Dog and Fire Hoses)," 1963. Collection of the family of Lonnie J. Wilson. Courtesy High Museum of Art.

VL: How would you qualify the reception of the exhibition by visitors, based on formal evaluation and/or anecdotal evidence?

JC: The visitors seemed to respond very well to the show. I think a good percentage were moved and inspired by the material. These pictures have the power to unleash personal memory and the comments that we received from our visitors (which are documented) reflect this.

VL: Given that the content of the show centered on activism and outreach, were any extra efforts made by the Museum to engage the community?

JC: We promoted the show in schools, colleges and community centers all over the city and hosted more than 10,000 schoolchildren. We made a big effort in our public programming to provide opportunities for the public to interact with photographers, activists and writers from that era.

VL: Lewis states, “These powerful images are not make-believe. They are real portraits of American history just the way it happened not too long ago in the Deep South.” What are the dangers in either allowing for or barring fictions in such potent photographs, which as you write, “bear witness?”

JC: I’d say that the fascination of these kinds of photographs (images that record or refract a specific event or action) are often more complicated than they at first appear to be. Vigilance and responsibility is required on the part of the viewer. Photography is in essence a way of viewing, of framing, the world and it is always just that–a point of view. With this kind of content, there is almost always another side to the story or an inference of another reality beyond the frame.

VL: Since you began work at the High after several years at the Getty, you have made an effort to highlight local collectors, photographers, and events such as ACP. I’m curious, how have your views of Atlanta and the arts community changed since your arrival in 2005?

JC: My views about the community really have not changed dramatically since my arrival. I was excited to move to Atlanta because I sensed that there was great energy among collectors and an eagerness for engagement with the High, and that has proven to be the case. We still have some way to go before we can consider the High a national leader in the photography field, but I firmly believe we are heading in that direction and agencies like ACP will help get us there.

VL: The High, along with artists in the Atlanta area, have at times been labeled “regional.” In your experience and exchanges with members of the local arts community, is it a term to be jettisoned or embraced?

JC: The use of the term “regional” is, I think, conflicted and misunderstood. The High is the most significant fine art museum in the region and as such, it is important that our mission and programs reflect an engagement with the concerns and preoccupations of our extended community. But of course, we also strive to be internationally and nationally relevant, while simultaneously producing projects that speak directly to our region. When I staged the exhibition New Photography here in the Summer of 2006, I made a point of including two artists from our community alongside or in counterpoint to two artists who happen to be based in New York. The four featured artists were Ruth Dusseault, Angela West, Sze Tsung Leong, and Taryn Simon. And by way of another example, our Folk Art collection is unique of its kind and has national relevance–while being largely regional in terms of its content.

Pingback: ART 21 Interviews Julian Cox, Curator of Photography at the High Museum | ACP Now!

Pingback: Black History in Atlanta: More than a Month | Parlour Magazine

Pingback: Black History in Atlanta: More than a Month | Parlour Magazine

Pingback: A trip to Cincinnati – Tales as a First Year Graduate Student