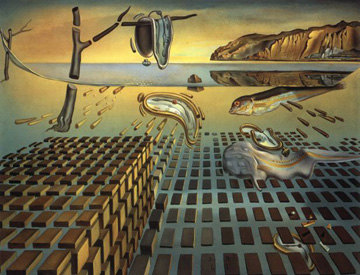

Salvador Dali, "Memory of the Child-Woman," 1932. Oil on canvas, 99.1 x 120.0 cm. Courtesy The Salvador Dalí Museum, St Petersburg, Florida.

A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to visit Melbourne, Australia. It is a wonderful city with a thriving art scene, the centerpiece of which is the magnificent National Gallery of Victoria (the NGV). I had the good fortune of arriving in the midst of Salvador Dali: Liquid Desire, the NGV’s ambitious—and Australia’s first—retrospective exhibition of the great Surrealist’s work, which runs until October 4.

While Dali never set foot on Australian soil and his art was rarely exhibited there, Australians first came to know his work through a painting titled Memory of the Child-Woman, which was part of an exhibition of modern art from New York that toured Australia in 1939. With the outbreak of World War II making it too risky to return the paintings to New York, Memory of the Child-Woman remained in Australia for several years, giving the continent an extended viewing of Dali’s brand of Surrealism, and causing quite a stir wherever it went. Salvador Dali: Liquid Desire marks Memory of the Child-Woman’s return to Australia, and it is most certainly a triumphant one.

This kaleidoscopic show includes over 200 works drawn from The Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida and Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres, Spain—two of the largest collections of Dali in the world. Liquid Desire traces a path through the artist’s long and peripatetic career, beginning with some of the earliest works from his adolescence, and through Dali’s journey across multiple continents and dizzying stylistic shifts, as well as his excursions into stage design, the fashion industry, television and Hollywood. The works included span from the dependable—the Lobster Telephone and screenings of Un Chien Andalou—to the unexpected—the lesser known belated pendant piece to MoMA’s The Persistence of Memory and wonderful examples from Dali’s excursion into jewelry design (including a jewel encrusted heart-shaped brooch that actually beats due to some hidden mechanics).

Salvador Dali, "The Disintegration of The Persistence of Memory," 1952–54. Oil on canvas. Courtesy The Salvador Dalí Museum, St Petersburg, Florida.

To my mind, there is nothing more exciting in blockbuster retrospectives such as this than the opportunity to glimpse a master coming of age by coming to terms with the past. Salvador Dali: Liquid Desire does not disappoint, as agreeable examples of the artist’s teenage excursions into Impressionism give way to more accomplished works, works which bear the residue of Dali having internalized the lessons of the great artists of the early twentieth century—de Chirico, Matisse, and Picasso chief among them. Indeed, for Dali, Matisse’s use of color and de Chirico’s haunting clarity of space and form proved catalytic.

The most revelatory moments of this sweeping show, however, are found in the rooms highlighting Dali’s glancing relationship with American popular culture and Hollywood while living in the United States from 1940-1948—a tantalizing period of possibility for a brilliant and singular mind to articulate his fantastical vision in unprecedented and unforeseen ways. One of Dali’s most spectacular—and now largely forgotten—early accomplishments on American soil took place at the 1939 World’s Fair in Queens, New York in the form of his “Dream of Venus” pavilion. As Liquid Desire reveals though a series of rarely seen photographs and supporting material, Dali’s contribution was classic Surrealist spectacle. Dali’s pavilion consisted of a fantastical grotto replete with a ceiling covered with opened umbrellas and dangling telephone receivers, so-called “liquid ladies” swimming around in large, glass water tanks, and mannequins interspersed with real, half-nude women dressed as mermaids reclining on satin-covered couches—an excessive, erotic tableau-vivant centering around a live Venus figure sleeping atop a sumptuous bed some 10 meters long. This theatrical and outrageous interior was matched by the pavilion’s exterior, which included an entrance that forced fairgoers to pass through an opening flanked by two female legs clad in stockings and heels, and a ticket booth shaped like a gigantic fish head.

To say the least, Dali’s World’s Fair folly was out of step with the otherwise corporatized pavilions and streamlined aesthetic of the “World of Tomorrow” themed fair. And if his 1939 pavilion stands as a testament to what might have been had Dali’s unbridled vision been fully scaled to the American culture industry, Dali and the American culture industry was, I would suggest, a relationship doomed from the start. After all, the environment that could have embraced his audacious vision had already evaporated by the time of his extended eight-year stay in America beginning in 1940, in no small part I suspect to the conservatism and aversion to risk that had by then creeped into various corners of American culture—trends which left little room for creative invention radically outside classical Hollywood forms. Indeed, in the wake of a Great Depression whose cultural consequences were in many ways a downscaling of ambition, Dali’s excesses and vulgarities at the World’s Fair seem fantastically out of scale with the sentiments of the age.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzzZa5o1q5k]

This ill-fated timing becomes an interesting consideration towards the end of the NGV’s exhibition. For it is not through Dali’s smattering of projects with Hollywood that were realized and moderately successful—including his contributions to Alfred Hitchcock’s Freudian inspired thriller Spellbound (most notably in the film’s famous dream sequence and stage set designs)—but rather the projects that remained unrealized—most notably an animated cartoon titled Destino that Dali began in 1945 in collaboration with Walt Disney—that tantalize the visitor with what could have. Storyboarded but eventually shelved in 1946 and later forgotten, it wasn’t until 2003 that The Walt Disney Company finally finished Destino, belatedly and painstakingly carrying out Dali’s animated vision with the aid of the recently rediscovered storyboards and other supporting material. It is a magical and haunting piece of animation. While I first saw Destino in a screening room Down Under, you can get a sense of what one gets when Dali’s erotic, surreal fantasy spaces merge with Disney’s beautifully rendered animation in this video.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog