Welcome back to BOMB in the Building, where each week we’re featuring a BOMB contributor relating to an Art:21 Season 5 artist. This is our final week before the official premiere of Season 5. We’ve had a great time digging around in the BOMB Archive these past few months, and hope you’ve enjoyed it as much as we have.

Artist Lawrence Chua interviewed Julie Mehretu for BOMB Issue 91, Spring 1995. “At the heart of Julie Mehretu’s paintings is a question about the ways in which we construct and live in the world,” he wrote five years ago. “I think of Mehretu’s paintings as going a long way toward articulating the disjunction of life as it’s lived today: as we circulate across reality and its mediations, constantly trying to reconcile daily experience with the peculiar light emanating from the end of the world as we know it.”

We can’t think of a better statement with which to end this portion of our “BOMB in the Building” series. Enjoy!

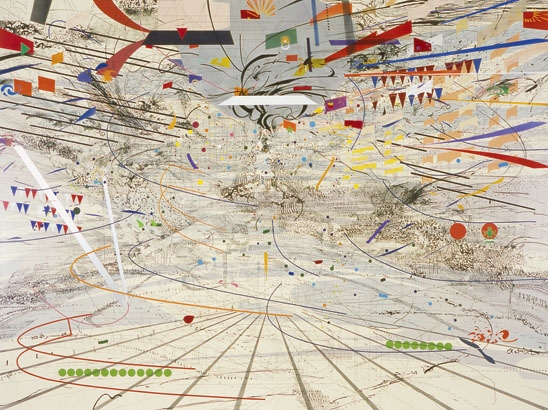

Julie Mehretu, "Congress," 2003. Ink and acrylic on canvas, 71 × 102”.

Lawrence Chua: To what extent are the paintings a critique? We’ve been talking a lot about current political events. . . .

Julie Mehretu: I don’t look at the paintings necessarily as critique. In fact, I’m not so interested in being critical. What I’m interested in, in painting at least, is our current situation, whether it be political, historical or social, and how it informs me and my context and my past. I am trying to locate myself and my perspective within and between all of it. I know I keep on going back to that, but it’s like, here’s a war and here’s the way that we’re treating the war, and how we’re experiencing the war. I was looking at some great Martha Rosler pieces recently, the Bringing the War Home photocollages which she began in the ‘70s. They are her images of advertisements invading the interiors of new homes, new homes designed for living in new worlds, but through the windows you can see soldiers fighting the Vietnam War. There are these interesting juxtapositions of what’s happening and what we experience. Of course there’s much more inherent critique in those pieces.

LC: That sounds metaphoric in a way that your paintings are not, which is what gives your work its power. We live in a moment that is obsessed with the Real. There’s this disjunction between physical daily life and the kind of extremely mediated reality we glimpse on reality TV or Fox News. Maybe it’s that disjunction that is being lived out in your paintings.

JM: When you’re writing, is it important to you to make that bridge between a situation that is happening right now and the eternal process of working and creativity?

LC: I begin with a structure and I try to have as clear an idea as possible about the structure and the way characters are going to move through that structure and the events that are going to propel them. The structure becomes set in a context, whether it’s the nineteenth century of Vanity Fair or the twentieth-century Gulf War. That context will influence language, rituals, actions, but I try to maintain the structure I set out to build. Colm Tóibín taught these writing workshops where he had the students begin by reading three Greek tragedies. His basic premise was that you could trace all Western narratives to these three tragedies, Electra, Antigone, and Medea. The truth of those relationships, those responses, are a part of our consciousness. So maybe a good writer is writing the same stories over and again. The context may make it a bit more relevant to the moment, but it’s not as if a mother killing her child isn’t incredibly relevant to current political events.

JM: The structure, the architecture, the information and the visual signage that goes into my work changes in the context of what’s going on in the world and impacting me. Then there’s this other subconscious kind of drawing, this other activity that takes place, that is interacting with everything that is changing, and it’s the relationship between the two that really pushes me. And why abstraction? There are so many other ways to make paintings about these conditions that I’m drawn to. But there’s something that’s hard to speak about that abstraction gives me access to.

LC: More and more I shy away from actually describing the physical characteristics of the characters. They almost become abstract figures that operate in a narrative. With the last extended piece of writing that I did, for instance, I was interested in how to completely absent race. I was interested in what kind of person the police were actually looking for on the occasions that they’ve stopped me. You know, what did that guy who robbed the grocery store that you mistook me for look like, exactly? Did we share some common historical reality? How do you begin to talk about the characters without using police language, or this mediated language that is ultimately unreliable, to identify them? For me abstraction is liberating. I read Chester Himes’s prison novel, Yesterday Will Make You Cry, and it is never really clear whether the characters are white or black even though he claimed they were white. He plays this funny game with them, their racial markers, their identities. That was one of the challenges for me in writing the last manuscript. How do you create these characters whose gestures are real and similar to the gestures that you live with in daily life without the burden of this mediated racial identity, while at the same time acknowledging the importance of race in shaping your reality? And now, I don’t want to do traditional area studies for my Ph.D. because what I’m interested in doesn’t just happen in Southeast Asia, it happens in Europe and it happens in the United States.

JM: Yeah. Even though I collect and work with images in the studio they don’t enter the work directly. Instead I’m trying to create my own language. It’s the reason I use the language of European abstraction in my work. I am interested in those ideas because I grew up looking at that type of work, but also not taking any of it at face value. It is as big a part of me as Chinese calligraphy or Ethiopian illuminated manuscripts. The more I understand any kind of work the more I see myself conceptually borrowing from it. Going to the Met and seeing particular paintings over and over inevitably becomes a part of my language. Abstraction in that way allows for all those various places to find expression.

LC: I wonder if that’s because language doesn’t come to us naturally because of each of our specific historical contexts. English or European abstraction is just not second nature to either of us. We meditate intuitively or self-consciously on whether this is the right word or the right gesture to use in this situation.

JM: I want to shy away from talking about your situation, my situation, as being more privy to a certain kind of understanding—

LC: I totally agree with you, but why are we more conscious of these uses of language? You were talking before about collecting images . . .

JM: Newspaper images.

LC: Right, and saying that to use them wouldn’t be as liberating as abstraction. Yet someone like Matthew Barney refers to some of the things we have been talking about. He also has a historical trajectory that he draws on where he’s not comfortable accepting a word or gesture at face value, and the discourse produced around his work isn’t reducing it to being about a potato famine.

JM: It’s the same reason that being from Addis Ababa and having lived in say Harare, Dakar, Providence, Kalamazoo, Houston, is not the point of departure for my work. There’s that desire to exoticize, but I don’t know if exoticize is the right word.

LC: That response is a kind of exoticization, but it’s a very sophisticated one. It’s certainly not as crass as it was in the 1980s, but it’s still a mediated version of our experiences: a kind of police report, or APB on our lives.

JM: I think the work is about trying to make sense of what is happening outside of that mediated reality. There are more and more of these complicated situations and I think we all exist in them, or at least I know I do, where I come from two different realities and I’m trying to locate myself. That was the point of departure in all the work, trying to make sense of the version of history and reality that my whole family in Ethiopia is living in, and another one that exists here with my parents and my grandmother and yet another one that I experience.

LC: Yes, but it’s that third part of the equation that is so crucial because it throws everything off kilter.

JM: Totally . . . (laughter)

LC: Like, there’s Ethiopia and there’s Michigan, but what about the Australian outback in your trajectory? Or, we understand why you were in southern Thailand when the tsunami hit or in New York City on 9/11, but tell us again why you were in Beirut?

JM: Right. (laughter) I think it’s that I’m seeking how to nurture that process of working in the studio while allowing other things to happen. Because the most interesting realizations happen there and that’s why I just want to work on only drawings right now: to allow for that kind of freedom and let those new kinds of languages and new marks arise to articulate a different picture of what’s happening in the world that, even though we’ve talked about it so much, I still feel really confused by.

Read the complete interview here.

Pingback: design wonderland » Blog Archive » The Curated Room: Julie Mehretu