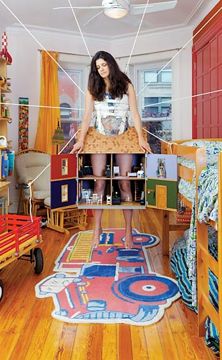

Janine Antoni, "Inhabit," 2009. Courtesy of Luhring Augustine Gallery

The following is part two of my discussion with Janine Antoni from last week. Be sure to catch her new show at Luhring Augustine Gallery, titled Up Against, through October 24th!

Joe Fusaro: Many artist-educators have to strike a balance between their work in the studio, the classroom, and even at home as parents. The current photographs at Luhring Augustine, such as Inhabit, are about being a mother so I was wondering how you strike a balance between being a professional artist and being a mother? How is that going?

Janine Antoni: (laughs) Well… my daughter is five. I’m still figuring it out, and as I figure it out she keeps changing, which means I never quite figure it out.

JF: I have a son that’s four, so I’m right there with you.

JA: I am not good at compartmentalizing—my preferred method is one of integration. One can see from my current exhibition that I have been preoccupied with my daughter for the last five years. The effect of her presence in my life is the overarching theme—she has definitely been leading me in terms of developing the work. As a result of the balance and flexibility that I have had to embody as a mother, I have completely loosened the terms of my production. There is more trust in my instincts in the moment of making. This is definitely the result of having spent the last five years trying so hard to be a good mother. I have also learned so much from watching my daughter play—especially early on, when she didn’t know what an object was used for. I loved the way she treated everything with such curiosity.

JF: And re-seeing it.

JA: And re-seeing it! Using it in a way that you would never imagine. I long for that sense of wonder in the studio.

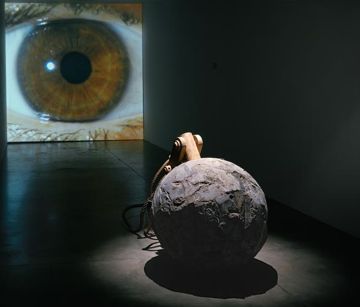

JF: I read about the new installation, Tear, after seeing the video for a few minutes. I went back after reading about it and experienced the work in a totally different way—relating the wrecking ball to the video. Do you feel viewers need the context or the story behind the work in order to appreciate it?

JA: I have very little control of that, so I have to let go after making the work. Ultimately the work has its own life. As far as control goes, the viewer’s physical experience of the work is the most important aspect of an exhibition to me, which is why I concentrate so much on the installation.

JF: I was very conscious about moving through the work.

JA: Right. At first one is attracted to the video, because it’s a moving image, but on seeing it again, one has more time to be with the wrecking ball. What you did was ideal in my mind, because you formed your own opinion and then you read my story. You had space to navigate between those two versions.

Janine Antoni, "Tear," 2009. Courtesy Luhring Augustine Gallery.

JF: It’s something we encourage students to do—to give work that you don’t fully understand a little extra time in order to see it. Not just to look and move on quickly. You mentioned at the beginning of our conversation about spending that extra time with things you don’t like in order to perhaps gain an understanding. If you gain an understanding about a work and still don’t like it, that’s fine. But if you gain an understanding and decide for yourself that you enjoy a piece for a specific reason, that can be such a powerful thing.

JA: That time you talk about is such a huge gift we can give ourselves, especially in regards to visual language. Our world is full of visual things, mainly advertisements, which are designed for you to understand in a second. What I’m trying to do is lengthen the way information is communicated, in order to let the viewer develop personal thoughts and questions. For example, with my current exhibition, one enters the gallery and sees these little copper gargoyles and wonders what they are, only to turn around and see a photograph that shows they are functional. This “slowing down” is one of the greatest benefits of contemporary art. I take great joy in producing something that slowly unravels and reveals itself to the viewer. I take great care in orchestrating the drama of that unfolding.

JF: So, as an artist and as a teacher, what’s next?

JA: As an artist, I am in a coma (laughs). Actually I am dancing and exploring different movement practices. As a teacher, I am excited to share the process of making this show with my students. It was five years in the making, so you can imagine the circuitous path I traveled. There is something exciting that happens when revisiting all the parts that failed on the way to making the final work. This includes all those who contributed to my research and production—from entomologists to stunt harness designers to wrecking ball operators. Collaborating with dozens of experts from outside an art world context definitely fed into the direction of each piece.

JF: What are you looking forward to?

JA: I’m in the midst of it now: simply taking the time to step back from the work, in order to figure out what I made, and just watch how it transforms by being in the world. This will give me a better sense of what I have communicated, and what I have failed to communicate, which will ultimately tell me what should come next.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Talking with Janine Antoni and Getting Set for NAEA: Part One | Art21 Blog