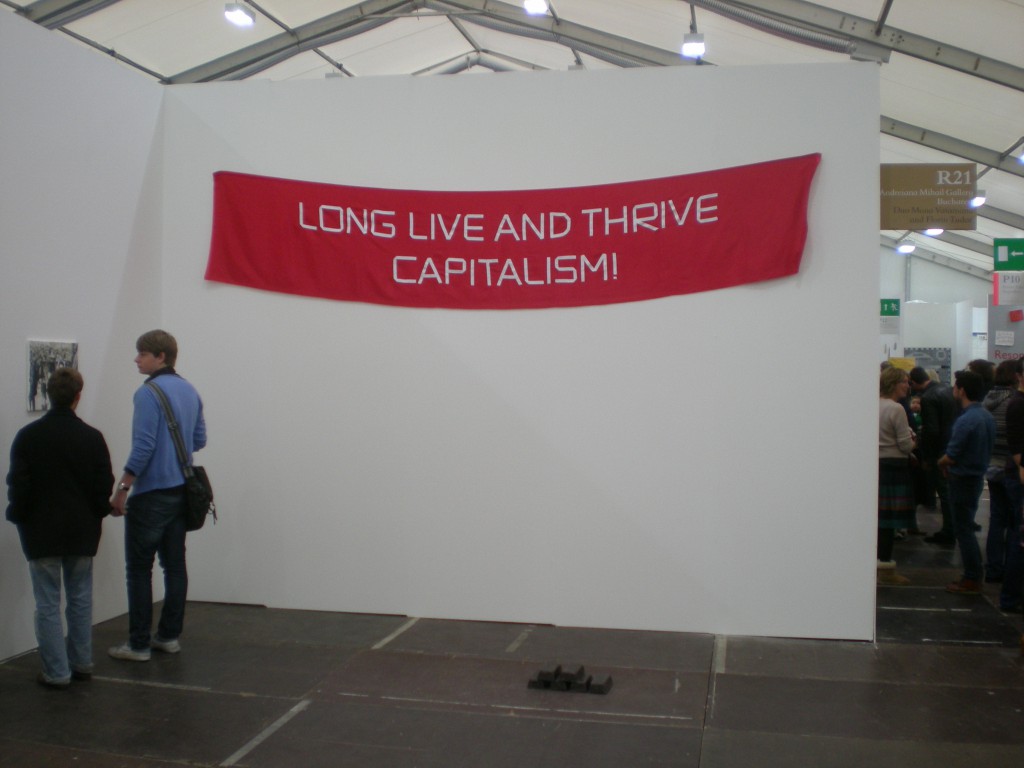

The Frieze Art Fair, like other kinds of trade fair, isn’t really designed for those outside of the trade it exists to buffer; it’s a bonus if you end up seeing things you like. The organizers’ great trick is to make a trade fair the hub of a weekend of frenetic cultural activity, with big-name museum retrospectives at Tate Modern, the Hayward, and the Serpentine strongarmed into a subsidiary role. Picture an agricultural show or office furniture exposition taking such a commanding presence in the wider culture and you get a sense of the strangeness of the way we experience art now (plus the fact that members of the public paid upwards of £20 to get in). To leaven the outright commercialism of the fair itself, there are the much-vaunted “fringe” events: Club Nutz, a recreation of “the world’s smallest comedy club” in Milwaukee, the SUPERFLEX collective’s series of short films about the financial crisis, experimental/spoken word radio station Resonance FM’s temporary lodgings in the midst of the fair, and Jordan Wolfson’s theoretical physicists discussing string theory at various strategic locations. For all their whimsical appeal, visitors can’t help but sense the sugaring of pills, even while nodding insiderishly at Club Nutz’s techno set played backwards, which sounded like Robocop having a migraine.

Strategically released rumors had it that gallerists were quietly confident about sales, perhaps since many plumped for sure-fire market winners. Current Turbine Hall occupant Miroslaw Balka’s rust-encrusted bric-a-brac popped up several times, as did Emin’s neon scrawls and wall-sized Gilbert and Georges. A lobby-sized Tuymans faced off against a lobby-sized Polke, as if daring collectors to make a choice. Thankfully, not all galleries played it entirely safe. Charles Ray’s hypnotic Moving Wire (1988) at Matthew Marks – aluminium wires slowly protruding from a hole in the wall, quivering under their own weight, then retracting turtleishly back – insisted on a quiet absorption impossible not to give. Jack Strange’s display of MacBooks at Limoncello, each belonging to a different friend of the artist, showed random flippings through their subjects’ iPhoto and iTunes collections, in what was ostensibly a kind of contemporary portraiture but ended up good voyeuristic fun. Art21’s very own Ida Applebroog showed a suite of scary and lush new paintings at Hauser and Wirth alongside a lovely, zinging Mary Heilmann called Some Pretty Colours. Sadly the Heilmann was drowned out by a pair of dirty socks; dumped on the floor in front of the painting, they’re a work by Christoph Buchel. Apparently they reached their asking price of $30,000, lending credence to the truism that a good sign in the art world is literally a sign of insanity in the real one.

Even in a comparatively sober year, Frieze has a carnivalesque brashness about it, and it’s interesting that the major museum shows (of which more next time) that have coincided with the fair’s brief dominance take up the circumspection that is touched upon, if briefly, in the fair itself. At Tate Modern, Miroslaw Balka’s installation in the Turbine Hall – a vast metal room on stilts, accessible by a walkway, whose interior is entirely, pitilessly black, entitled, with weird post-Jacksonian resonance, How It Is – must have been an extraordinarily enveloping experience when first encountered (in other words, in its embryonic press-view state). Sadly, its location sets up certain expectations (light-heartedness, accessibility, interactivity) established by earlier occupants of the site, and the clanging of feet on the metal floor, and the hovering blue squares of mobile phone screens, make it feel like The Buchenwald Experience.

If you’re an artist installing works in an existing museum building, you can either accept the limitations of the space and the collection, or – if you’re Damien Hirst – you can rehang entire galleries in stripy linen to show your latest works to maximum effect. His latest show, entitled, with a characteristic blend of pomposity and unwitting irony, No Love Lost, is a display of paintings made (and this has been used as a selling point, astonishingly) entirely by himself. That they’re weak ’50s Bacon rip-offs knocked out with breathtaking ineptitude is not really the point. The point is that Hirst has been able to wangle decent gallery space inside the Wallace Collection, in the historical collection’s first ever show by a living artist. It’s another example of historical collections’ craven and weak-kneed approach to contemporary art. With an eye on one of Hirst’s gloopy, gloomy skull paintings, you can look through to a Poussin. Guess who looks more conservative, small-souled, and joyless? Go on, guess.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog