This July, I’ll be teaching a course I developed on the intersections of contemporary art and science, for Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). My students are advanced high schoolers, attending two-week courses on physics, robotics, aerospace engineering, and biology, among other lab sciences. Many of them have had no academic art experience. We begin the first day by discussing where the boundaries might be between the two disciplines, listing responses to “what do scientists do?” and “what do artists do?” Experiment, create, observe, invent, analyze – they quickly realize that there are many overlaps, but no clear divisions.

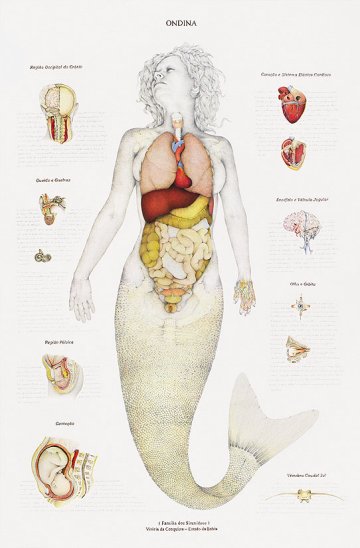

Mark Dion noted in Art:21 Season 4 that humor, irony, and metaphor are tools artists have that scientists don’t. Or, as a recent New York Times review of the exhibition Dead or Alive at the Museum of Arts and Design (New York), put it – “artists are allowed to make stuff up and scientists really shouldn’t.” Is truth, then, the burden of scientists? This has been fertile ground for contemporary artists like Dion, Walton Ford, Alexis Rockman, and Walmor Correa, among many others. Their work challenges both the authoritative scientific voice and the structure of its presentation.

I’m interested in raising this question here, as I do in my classroom, because it continues to be a point of debate in the academic community, as it relates to practicing and teaching the two disciplines. Over and over again in current discussions about education, an interdisciplinary approach is stressed, and the Renaissance is held up as the ideal academic environment, a time when intellectual pursuits were not as narrowly defined. Leonardo had it made, we’re led to believe, because he could work fluidly between what we now know as art and science.

2009 was the 50th anniversary of C.P. Snow’s influential lecture “The Two Cultures,” which brought about a fresh round of debate on his claim that the communication breakdown between the sciences and humanities was to blame for global problems. Ironically, Snow’s lecture is often blamed for widening the disciplinary divide. David Ng, editor of the Science Creative Quarterly, wrote in Seed Magazine last year that “it’s not really about two cultures, those two distant columns of knowledge representing art and science. It’s just about ‘people liking different things.’ Many people are frustrated by this, but many people celebrate it. Perhaps most importantly, everybody knows this to be true already.” Could it really be that simple? Author Martin Kemp would seem to agree, suggesting that, “We can be students of the visual – rather than concern ourselves with distinct categories called art and science.” Perhaps my favorite salvo on this topic comes from a comment on the science/culture blog BioEphemera, where reader arvind noted, “I wish more people would understand that the scientific enterprise is merely the most difficult and constrained artistic enterprise ever embarked upon by humankind. When I hear the words ‘art versus science,’ it feels like a nonsensical statement — like saying ‘art versus the most creatively draining art humanly possible.’”

Thinking pragmatically, perhaps one of the most crucial reasons to keep artists and scientists coming together is the wider audience that naturally follows interdisciplinary projects, paramount for the global scale of today’s concerns (C.P. Snow was at least correct on that count). You can preach about the benefits of environmentalism, for example, but maybe experiencing Chris Jordan’s photography or Brooke Singer’s Superfund365 archive or Amy Franceschini’s Futurefarmers projects (all on the syllabus), will not only inspire action but new methods of acting. I hope to show my students examples of makers and thinkers who approach the lab as a studio and the studio as a lab. These boundary-crossing practices can open up discussions about how we learn, think, approach problems, and process information – in short, how we navigate our surroundings.

The League of Imaginary Scientists, “a non-exclusive society for creative scientists, mechanically-inclined artists, absurdist inventors and self-proclaimed quacks,” is one model for interdisciplinary inquiry that I present to my students. “In pairing science and art, the League seeks to formulate new methods for data expression, embodied through interactions that produce physical artifacts and accompanying scientific residues. League projects provide opportunities for the exchange of knowledge among collaborators, present and implement a methodology of “art as experiment,” and transform the process of intellectual inquiry into an interactive medium.”

Saving the world and having fun doing it? If I can impart this lesson to my high schoolers this summer, that’s no small success. Ultimately, what I hope to convey is an expanded way of seeing and thinking. I hope the art vs. science debate rages on — not to keep the fences up, but on the contrary, to continue the dialogue. As the League has said, “finite results are not the creative objective. These artists and experimenters are not merely propelled by curiosity, they are compelled to connect.”

Pingback: Mapping our way back | Art21 Blog

Pingback: What Makes Us (More) Human: The Vast Middle Ground Between Art and Science | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Alison Ruttan’s “The Four Year War at Gombe” | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Thinking Through The Relationship Of Art, Science And Business - PSFK

Pingback: The Art21 Blog’s Most-Viewed Posts of 2010 | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Resources » Is truth the burden of scientists?