Yoshitomo Nara, "The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand," 1991. Acrylic on cotton: H. 59 1/16 x W. 55 1/8 in. Image courtesy the Asia Society Museum.

For those who enjoy Yoshitomo Nara’s mischievousness characters and pop-culture inspired iconography, or those who are not yet familiar with them, the current show at the Asia Society in New York City, Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, will no doubt be a revelation. One of the key figures of the Japanese Pop movement of the 1990s, Nara is perhaps best known for his portraits of solitary children who are as menacing as they are cute. Rendered with a child-like simplicity and straightforward use of color that belies their often insolent and defiant posture, Nara’s cast of recalcitrant characters is well represented by a number of important paintings and drawings.

Among them is The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand, a simple, cartoon-like painting of a little girl in a bright red uniform and matching beret looking up unflinchingly at an implied viewer who dwarfs her, her impassive expression and sturdy stance becoming alarmingly aggressive on account of the small knife clenched in her hand. Many other iconic works are on display besides The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand, and seeing them together allows a fuller appreciation of the tension in Nara’s work between his cartoon-like imagery and their careful execution and dark themes.

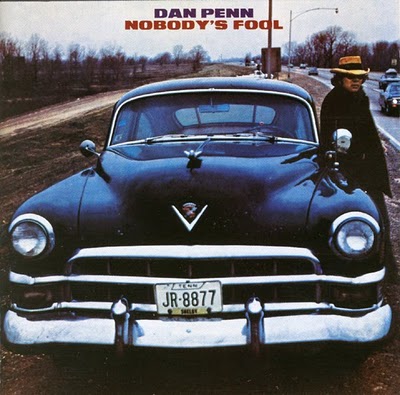

One of my first revelations actually occurred before I even set foot inside the exhibition. To my mild disappointment, given the musical theme of the exhibition, I realized that the title of the show was not a reference to the song “Nobody’s Fool” by the 1980s band Cinderella (yes, that fantastically big-haired, highly stylized glam band), but rather to a 1973 album by American soul musician Dan Penn. Nara referenced Penn’s album in a 1998 watercolor and as this exhibition reveals, it is but one of many musical allusions in Nara’s art—from Penn and Neil Young to the Ramones and Green Day.

I will admit that I was slightly embarrassed, going into the Nara exhibition, that Cinderella would be my first popular cultural reference point, especially given my assumption that Penn and his 1973 album (neither of which I had ever heard of before) must be some sort of authentic, expressive rock album seeping with an angst and defiance from which Nara drew inspiration. Penn, I speculated, must certainly be heaps more authentic than the commercialized musical chords and mannered stylings of a band like Cinderella, whose aesthetic and music seemed to delight self-consciously in the clichéd visual and sonic codes of rock and roll. But I couldn’t have envisioned then just how prophetic my innocent invocation of that glam band would be by the time I exited the Asia Society show. But more on that in a moment.

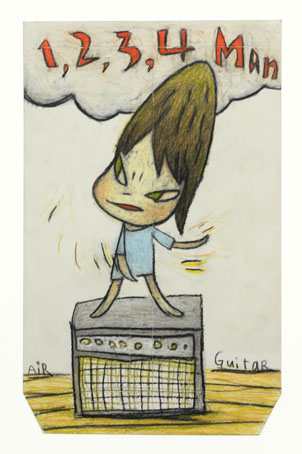

Yoshitomo Nara, "Untitled (1, 2, 3, 4 Man)," 2008. Colored pencil on envelope. H. 14 1/2 x W. 9 in. Image courtesy of the artist.

Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool foregrounds the artist’s numerous references to and shared sensibility with rock and punk music. For me, the exhibition’s association of Nara’s art with the energy and spirit of rock and punk does provide a welcome contextualization of the artist’s iconography and themes, for it is a perspective that allows for a number of interesting insights and revelations both large and small (Nara a ceramicist? Who knew?). It was a surprise to learn, for example, that The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand was inspired by the song “Slash with a knife” by The Star Club, one of Japan’s first punk bands. When considered in this exhibition’s context, the punk ethos of Nara’s art seems clear as his paintings and drawings skillfully turn the abstractions of adolescent angst and rebelliousness so central to punk and rock music into a visible and palpable experience. Such a context allowed me to appreciate the angst that pervades many of his works, and the fact that while Nara’s children often seem defiant, the reasons for their defiance remain elusive. At its purest, the music with which Nara felt a kinship was an expression of defiance, yet it was also music that operated from a position of social alienation and isolation, and was often unable to define its opposition beyond a general ambivalence toward the strictures of the mainstream. Perhaps this helps to account for why Nara’s little girl in the posh beret with a knife clenched in one hand looks up defiantly at an adult world of which she is not a part, seeming as vulnerable and alone as she does insolent or rebellious. As a cultural form, rock and punk music played an important role in the production of individual and collective identities, and this show lays out Nara’s own identifications and affinities with the youth culture and counter-cultural themes of independence and self-reliance associated with such music.

In fact, the Asia Society exhibition suggests that the general tenor of Nara’s characters—defiant yet with an almost apocalyptic sense of isolation and angst—has its roots in the artist’s own solitary childhood, a time when he found solace in similarly minded rock and punk music. But I couldn’t help wondering if there might be an alternative reading of Nara’s interest in rock and punk music besides this exhibition’s psychobiographical perspective (“[Nara’s] sense of isolation was profound, even for someone who had spent much of his childhood alone,” the introductory wall text divulges). That is, despite the seemingly authentic rock and roll attitude evident in Nara’s art, one should not also forget that Nara’s aesthetic and artistic sensibility is rooted in the surface values and stylized, mass produced imagery of Japanese popular and consumer culture.

As I walked through the Asia Society’s galleries, I thought about whether the close connection between Nara, rock, and punk music is not only on account of some shared expression of alienation and defiance, but perhaps also an acknowledgment and exploration of just how quickly that expression can become a mannered, repeatable style in music and art. That is, perhaps Nara’s articulation of childhood angst—be it his own or in general—also foregrounds just how closely connected authenticity and artifice are. Another aspect of Nara’s attraction to punk and rock might lie in what is also one of the paradoxes of rock and punk rock: that authentic self-expression necessarily involves the performance of certain conventions influenced by and circulated in popular cultural articulations of angst, alienation, or rebelliousness. While the Asia Society’s consideration of Nara’s art as punk rock-inspired confessional does not really accommodate this reading (the introductory text proclaims that the exhibition “helps us understand Nara’s internal world”), there are hints sprinkled like breadcrumbs throughout the exhibition that Nara might also be exploring whether such internal expression is, like so many things in this time of mass culture, invariably also an affectation shaped by external forces.

I first began considering this possibility when I realized that the early Japanese punk and rock bands in which Nara was interested were heavily influenced by English and American musical groups. In a kind of hall of mirrors effect, these Japanese bands appropriated from their Western counterparts a look and sound of youthful rebellion that had already become mannered and stylized. Indeed The Star Club, the very band that inspired Nara’s The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand, employed a musical sound and performance style that was conspicuously and self-consciously distilled from exported Western punk rock conventions.

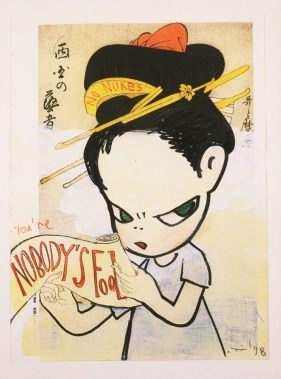

Yoshitomo Nara, "Untitled (Nobody’s Fool)," 1998. Watercolor on paper 13 3/4 x 10 1/8 in. Image courtesy the artist.

But one of the first breadcrumbs came in the form of the work that gives this exhibition its title, Nara’s 1998 watercolor Untitled (Nobody’s Fool), which yields clues that this “hall of mirrors” effect might indeed be an important facet of Nara’s work. Nobody’s Fool, which the wall text claims is Nara’s way of paying homage to the individualism of Penn, whose album title Nara references, consists of a drawing of one of Nara’s insolent adolescents rendered atop a reproduction of a 18th century ukiyo-e print by Kitagawa Utamaro. Given the work’s apparent tribute to individualism, it seems odd that Nara would use a ukiyo-e woodblock print, a stylized form closely associated in its time with mass advertising and the popular consumer culture of Edo’s (Tokyo’s) theaters, cafés, and geishas. In fact, Nara’s use of this particular image seems instead to support an impersonal, extroverted reading of the work. Utamaro’s period prints were mass-produced commercial artifacts that not only proved popular in Japan, but also circulated widely throughout Europe in the latter half of the 19th century during a particularly intense period time of the West’s fascination with and appropriation of Japanese visual culture. Moreover, Untitled (Nobody’s Fool) contains a number of clichés both past and present, including that of a Japanese girl with a chopstick bun hair style and the phrase “No Nukes” written on her headband. These clichés seem to level any distinction between conventions of the distant past and those of the 1960s and 70s, and complicate the ideal of authenticity and individuality alluded to in the accompanying wall text.

To my mind, the possibility that Nara is in fact concerned with this echo chamber of meaning, influence, and authentic expression becomes clear in his installation, Doors (2006). One of a handful of extraordinary installations in the show that Nara made with his long-time collaborator Hideki Toyoshima, Doors consists of five separate rooms—scaled to feel like a child’s clubhouse—that one can enter, each with chalk-like scribblings on the floors and drawings tacked up on the wall. Tacked up on the inside of one of the open doors like a child’s artwork is a single glossy sheet of paper on which is printed a quotation from Billie Joe Armstong—the front-man for the punk rock band Green Day—which reads as follows:

I read this story about how the writer Richard Bloch—who wrote these great crime and horror novels in the forties and fifties—inspired mass murderer Ed Gein and his killing spree. Richard Bloch, who had no idea that his writing inspired Ed Gein, wrote the book Psycho (which later became a successful movie that then inspired other movies like Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Silence of the Lambs) because of Gein’s murder spree. Was it the artist inspiring the killer? Or was it the killer inspiring the artist?

Nara’s inclusion of Armstrong’s “chamber of echoes” quote about how meaning is generated makes me think that considering Nara’s associations with music as a way of gaining access to the artist’s “internal world” might miss a larger point about authenticity and artifice, namely the prospect that such accessible interiority—the authentic, individual expression of adolescent angst, rebellion, or alienation—is necessarily formed and informed by a range of pop-cultural influences, including cartoons, punk and rock music, movies, and TV.

I found one final breadcrumb when I wandered into the exhibition’s final room. There, located among 100 rock album covers selected by Nara and hung on the gallery walls, was Dan Penn’s 1973 record, Nobody’s Fool. Finally standing before the album cover that is the literal and metaphorical referent of Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, I found myself looking at it with great curiosity. The cover consists of a photograph of a young Penn leaning against his 1949 Cadillac on the side of a highway somewhere in the heartland of America. Wearing sunglasses and a hat pulled low, he has his hands stuffed inside a heavy jacket and a cool, slightly recalcitrant expression on his face as he looks toward the camera. Taking in the image of Penn and thinking once more about Nara’s art, I can’t help but appreciate the way in which the album cover mobilizes the requisite signifiers of a ruggedly self-determined, loner-on-the-road rock and roll existence, and employs the conventional signs of a romanticized counterculture struggling against the strictures of mainstream society. With my thoughts turning one last time to Nara’s art, I couldn’t help but think to myself: “how fitting…”

The Asia Society exhibition, Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, is on view now until January 2, 2011.