Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe, "Bright White Underground," Installation view, 2010. Courtesy Country Club Projects.

A few weeks ago, when a friend was planning a visit to New York City, he asked me which art to see. I found myself prefacing less-emphatic recommendations with, “it might not change your life.” That’s just something people say, of course, but I was serious. I really wanted my suggestions to have life-changing potential and if it that potential was low, I felt I owed him fair warning.

When I first considered the question that started this series–“How do we experience art?“–I found its openness overwhelming. But what I actually want from the experience of art is just as open. It’s also tenuous and, paradoxically, demanding: I want my life to change.

A recent installation by Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe seemed like an enmeshment of everything I want art to grapple with: drama, quietness, self-awareness, believability, irreverence, smartness, artifice, density. The two artists subverted an icon of mid-century modernist architecture, turning Rudolph Schindler’s Buck House into a cave-like relic of a counter-culture moment. They invented an obsessively detailed narrative that they almost seem to believe, reenacting and documenting specific events that could have happened but never did. And yet the narrative is secondary to the confusing reinterpretation of the Buck House that acknowledges and totally obscures the austere clarity of Schindler’s original design. This conversation with Freeman and Lowe, which explores the experience of viewing, making, inventing, and living with the world you’ve created, seemed a suitable close to the Art and Experience Flash Points series.

Catherine Wagley: So my first experience of the space came from reading the press release—which was beautifully written, by the way. You two did that?

Jonah Freeman: Yes.

CW: I enjoyed the dot connecting approach to history it took. It presented a fictional history, but invited potential visitors to suspend disbelief and peel the space’s history away. But then I read the T-Magazine piece, which was so bombastic—and “drug addled.” You two become characters, described in specific physical detail, even. The press release and T-Mag article seemed to collide the night of the opening. People tended to react to the space as an extreme, irreverent project but it also felt quiet and careful at times. How do you reconcile those aspects?

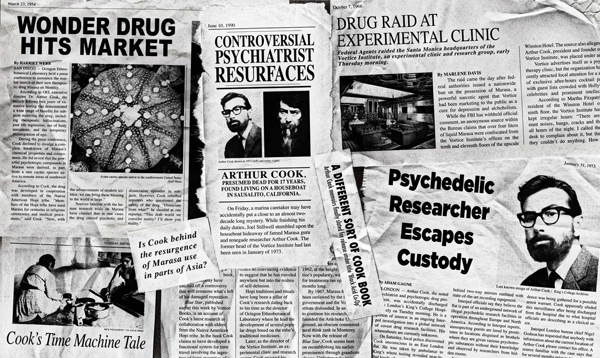

Justin Lowe: I guess it does appear as though there’s some carefully constructed casualness. I mean, the mess is rather specifically accumulated and controlled, wouldn’t you say? This stuff back here is all from labs and there are gently generated newspapers that have helped us tell some of the story. There’s lots of coded language utilized within the piece. You’re supposed to experience something that’s polysemic, open, and expansive.

Freeman and Lowe, "Bright White Underground," installation view, 2010. Courtesy Country Club Projects.

JF: It is theatrical but lots of effort went into playing that aspect down, so it doesn’t feel like spectacle. You’re not bombarded by the artifice. We always wanted it to feel like actual rooms, not like a set.

JL: There are real signs of the house’s previous function. There’s a reason why it looks like this.

CW: With the past shows I’ve seen in this space, there’s a sort of deference that artists tend to show the architecture–they do this at [Schindler’s] Kings Road House, too. Your installation defers as well, but differently.

JL: There’s definitely somewhat of a perversion of what Schindler directed. He wanted this open floor plan, sight lines into all the rooms. We tend to have a definitive path through our pieces [and] to give you glimpses of what’s right in front of you. We did these architectural interventions . . . through white-mirrored ducts that allow you to look into a room you won’t get to for a while. And when you do get there, it will already be filtered through some other kind of edifice.

Freeman and Lowe, "Bright White Underground," view through one of the ducts, 2010. Courtesy Country Club Projects.

JF: The ducts were a real response to the open plan of the building. Since we were going to chop the house up, we wanted to maintain some of that. This project was harder than the others because the context was so specific and the content so intense. In Schindler’s work, there’s so much focus on bringing the outside in and there’s all this natural light, and that’s what we’ve been against with our installations. We’ve been making composed worlds where you have no sense of the outside.

JL: That’s how some decisions, like making the earthquake room [a room with mirror-covered walls in which the floor cracks open and rises up], got made. How could we bring the outside in? And this project has always been somewhat of a coin, reflecting the area we’re in. Some of Los Angeles’ earthquake paranoia is found here, in this mirrored room.

CW: It seems like the narrative enabled . . .

JL: I think the narrative enables quite a bit. It sets this up as a house abandoned in the mid-60s. We wanted it to seem like the home of people who had been doing lots of psychotropic drugs while renovating their home and so not following the normal logic of space. They were trying to turn the building into a different kind of experience.

JF: There was quite a bit going on with LSD before the counterculture really caught up. It was this drug developed by a scientist and then used by the government, either as a truth serum or weapon–a Manchurian candidate type of thing–or even a healing tool. That was more interesting to us than the psychedelic culture that we all know. In this case, this building seems really appropriate–for one thing, it’s in California, which is where a lot of this experimentation was happening in the 50s and early 60s.

CW: That’s why your narrative is believable. It doesn’t ask people to suspend that much disbelief.

JF: We’ve tried to keep it close to what happened. It’s easier that way because then you just have to change the details.

CW: Right, and then there’s Rudolph Schindler. You’ve talked about needing to pervert the space, but what Schindler was doing was bizarre in itself. He wanted to create a communal experience. At the Kings Road house, they didn’t have bedrooms. They slept in the open air and then there was a roof space specifically for dancing when they had parties—spaces designed for a life that would somehow transcend what was normal.

JH: We were told by an architect that Schindler would actually appreciate what we’ve done. These houses weren’t as precious as they seem to us. You know, this almost feels like a cathedral. And it’s often treated like one. For us to get an opportunity to do this was rare; it probably will never happen again.

CW: Which brings me to your title: Bright White Underground. When I hear “bright white,” I think of the house’s brightness, of course.

JL: It’s definitely bright here. There are so many ways in which these titles come about. They’re usually riffs on things.

CW: They often feel familiar, like lyrics. But I Googled Bright White Underground and it’s not anything that exists.

JL: It’s associated with the type of social experiment we were purporting to have happened here.

JF: What happened in this house was definitely underground.

JL: This “underground” is kind of elite. It’s secretive, something that’s conspiring toward social change and a shift in consciousness. It’s basically trying to expose some of the darkness of the subconscious. Only, it uses an explosive technique as opposed to meditation or something of that nature.

Freeman and Lowe, "Bright White Underground Archive #7," framed silver gelatin photograph, 2010. Courtesy Country Club Projects.

JF: You know, I always think of [the experience of these installations] as moving through a new city. There’s a certain familiarity to it but a lot of things are different, so your senses are heightened. It’s like the effort to create all these fictions, movies, and books and drugs is about taking people into a parallel reality that makes them aware in a different way. That’s where unusual connections are made, in that space of heightened awareness.

CW: Part of what I like is that you’re not saying, “yes, we know we’ve created a fiction.” It’s more like you’re saying, “here’s the timeline; join us in this story.” I understood how you’ve built this fiction and I felt free to access it in the way I want to.

JL: It’s a world that easily could have been.

CW: And maybe the space for making a connection between past and present, fiction and reality, is the richest thing you’re giving us. You’re giving that to yourself, too–giving yourself more narrative fodder for future work. What’s it like doing this?

JL: Every time we do this project, our lives change dramatically. Where are we based now? We’re in a transitional phase.

CW: The project becomes your life, in a way?

JF: Almost too much.

JL: It matters which time of day you ask us that.

JF: Though now that we’re done, there’s a void.

JL: We’re not even done. We have all these bands that are using the house as a recording device. We’re working on this film treatment, and there’s general maintenance to deal with here. It is our life.

Pingback: Bright White Underground « 1 Weird Old Tip