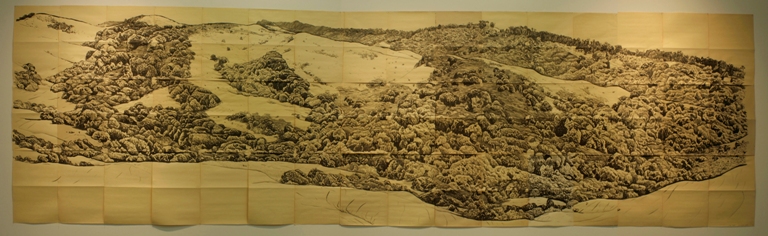

David Wilson. "Heal Again," 2009. Sumi ink on found paper, 60" x 192". Courtesy the artist.

My hometown of Lafayette, California, encompasses a 925-acre nature area, the boundaries of which press up against the town’s suburban roads and cul-de-sacs like a face against glass. When I was a teenager, I spent my afternoons hiking its trails, spying on the town’s happenings from these wooded and shrouded routes. I peered into neighbor’s backyards, watched carpools snake around curves, witnessed swim lessons and soccer practices from afar. I began to know the town from how it appeared when I was in the hills, and began to look toward the hills for comfort when I was standing in town.

In many Northern California locales, town and country similarly intertwine to create inverse versions of the same place. Nature, however mediated, dances at the edges of our cities and dissects our town centers, offering a visual respite from our highways and shopping malls. If you are stuck in traffic, look left to the Pacific Ocean; if you are crossing a crowded street, look right to a ridge line on which eucalyptus trees wave in the wind.

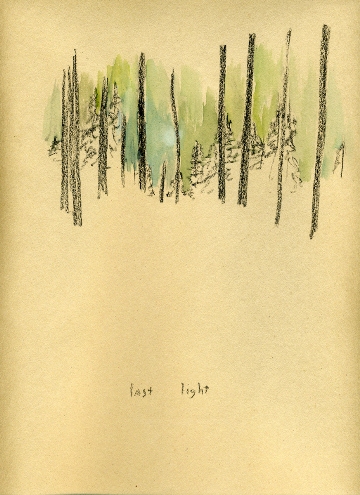

David Wilson. “Last Light,” 2008. Watercolor and charcoal pencil on found paper, 10 1/4" x 14 1/4". Courtesy the artist.

Incorporating drawing, watercolor, and social gatherings, David Wilson‘s artwork draws attention to the boundary between the Bay Area’s settled regions and what lies just beyond them. The East Bay hills, a backdrop to the cities of Oakland, Berkeley, and Richmond, are a frequent muse, serving as subject matter for his illustrations and a setting for his communal gatherings. Although the city is not typically represented in his drawings, its presence is always implied; it is only from the city that the natural world can beckon so unabashedly as a refuge.

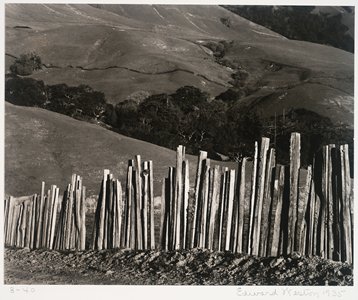

The relatively young artist’s work exists within a loose trajectory of artists who have taken California’ s landscape as subject matter, often treating it “as an end in itself, complete on its own terms,” as Kevin Starr writes of photographer Edward Weston’s images in California (UC Press, 2005).

Edward Weston, “Ranch, Old Big Sur Road,” 1935. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Wilson also takes the California landscape “as an end in itself,” though he is driven more by an urge to document it than romanticize it. His eclectic practice’s unifying theme is its advocacy of observation. The drawings, paintings, and experiences that result from this deliberate act of looking are, in some respects, secondary.

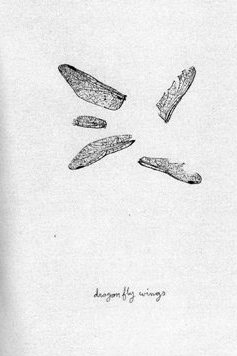

Many of his pieces carry the weight and tone of primitive scientific research. A series of taxonomies presented in the artist’s book Collecting Drawing (Little Paper Planes, 2009) include detailed drawings of broken dragonfly wings, acorns, seeds, and shells. Natural forms are arranged, studied, and recorded as though they are new additions to an ongoing archive. While Weston makes bell peppers, shells, and succulents exotic and foreign, Wilson renders such objects intimate and knowable.

David Wilson, "Dragonfly Wings" from "Collecting Drawing" (Little Paper Planes, 2009).

Drawings function as records of time passing and of place in Wilson’s artist’s book Walking Drawing (Little Paper Planes; 2009). Prefacing the collection of sketches, he writes: “I sometimes take walks with a piece of paper. I try not to look for the thing to draw, but to be patient and ready to draw at the moment I feel I have arrived. These drawings are moments of arrival and records of the places I have walked.” The resulting images tell a story of encounters–with neighborhood birds’ nests, heavy skies, Little League baseball diamonds, and even sand dunes.

Heal Again (2009, at top of post) is a large drawing that subtly alludes to the physical and temporal conditions of its making. The work is both a representation of the hills above Richmond, recently ranked the sixth most dangerous U.S. city, and a record of the artist’s multiple trips to the site. These serial visits are expressed in the piece’s individual sheets that are arranged together to create a whole. The impression is one of accumulation, as individual encounters with a place amass to create a complete vision.

David Wilson, "Angel Island Gathering," July 12, 2008. Photo: Alissa Anderson. Courtesy the artist.

Wilson’s tendency to direct his audience away from his images toward the conditions of their creation seamlessly leads to his practice’s social component. As with his other work, his communal gatherings highlight the edge between city and nature. There was the musical performance on an uninhabited island in the San Francisco Bay, the happening at a beach just north of the Golden Gate Bridge, and the Memorial Fort, built of woven tree branches in the East Bay hills.

In my next post for the Art21 blog, I talk to David Wilson about the Memorial Fort, the social component of his art practice, and his recent residency at the UC Berkeley Art Museum.