Tonight, I am sitting in a red booth at Formosa Café in Hollywood, the Cantonese restaurant Frank Sinatra reportedly frequented when heartsick over Ava Gardner. Lana Turner came here too, and danced with gangster beaus in the bar’s center aisle. My friend L. and I have both just finished a hectic work day, and we wanted to meet somewhere that had a history. We’re here not because of Frank and Lana, however, but because a red-headed painter we both know, a woman who makes fluid oil landscapes and talks about the purity of the spirit, first kissed her husband in one of these booths.

Whatever magic was hanging around when that kiss happened must still be here, because L. is telling amazing stories. She tells one about a burlesque performer named World Famous Bob who once lived in her New York apartment building. One night, Bob performed a reverse strip tease, going from exposed to fully, opulently clothed. L. had never seen vulnerability expressed so movingly before, and her description convinces me that I never have either. In fact, as the image sears its way into my brain, I decide that everything I write this week will be a thank you to L. Not because she needs my thanks, nor because this new-found image of vulnerability will even be legible in what I put out, but because I’m pretty sure other people are the whole point: you put ideas into the world to give back to those who give to you, and you hope that, if what you say or make feels true to those you care about, it means you’ve become a slightly better friend.

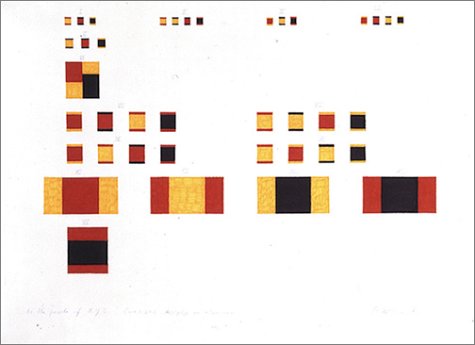

Blinky Palermo and Imi Knoebel, both German, born at the tail of World War II, and students in Düsseldorf during the ‘60s, put ideas into the world for each other. Imi made one of his best known works, 24 Colors—for Blinky (1977), as a tribute to the friend he called “master of color.” Even though Palermo had died the year before and would never see 24 Colors, the installation was made more for him than the rest of us. Installed at DIA Beacon in upstate New York, it consisted of 24 individual panels, each of which evoked a colored shape totally free of right angles (Blinky loved equilateral triangles and his edges were often not-quite straight).

The colors, all right out of the tube, included green, orange and pink, in addition to the primaries. Sometimes they almost looked fluorescent, a tendency more in line with Imi’s sensibility than Blinky’s. In fact, the whole installation, while a reflection of what Blinky Imi perceived, is like nothing Blinky would have produced.

Independently, the two artists had changed their names—Imi from Klaus Wolf to an abbreviation of “goodbye” and Blinky from Peter Schwarze to the name of an American Mafioso. Together, the two studied under Joseph Beuys and alongside Jorg Immendorff, befriending Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter. Their fascination with Malevich and simple affection for color and form—affection too down-to-earth to be full-on minimalism, too crisp to be pop, too clean to be a riff on expressionism—separated them from their mentors (according to Imi, it was Beuys’ agitated, searching attitude, not his aesthetic, that made him the right teacher for them). They shared a reverence for America, too, though Blinky’s Yankee envy outstripped Imi’s.

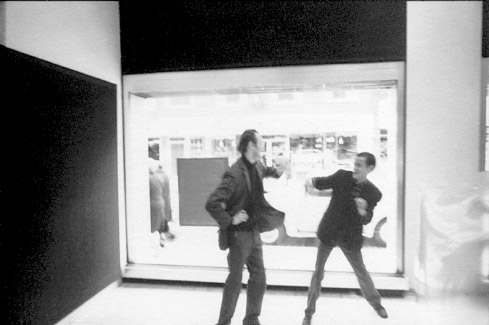

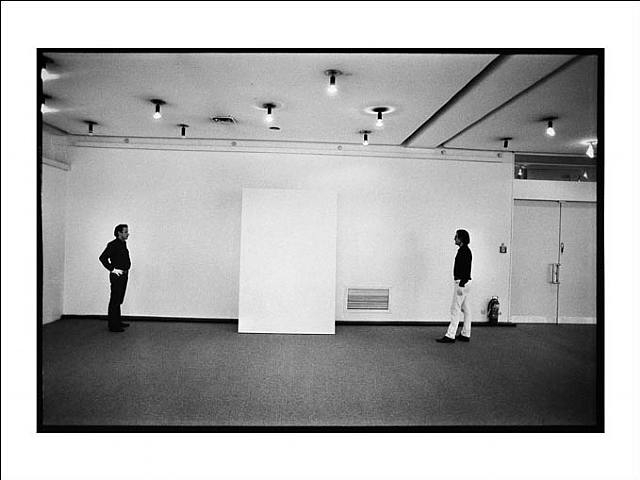

Dietmar Schneider, "Blinky Palermo und Imi Knoebel, Düsseldorf, 1975," 1975. Courtesy Galerie Bugdahn und Kaimer.

When Blinky finally moved stateside in 1973, he was in a dry spell (his cloth paintings felt like an “impasse,” says art historian Christine Mehring). His move to New York didn’t help. He’d begun experimenting with metal grounds, but continued to destroy everything he made for nearly two years. Then, in 1974, Imi came to visit, and the two took off on a sprawling road trip. They stopped at Rothko’s Chapel, saw De Maria’s Las Vegas piece, and returned home inspired.

It’s a perfect American story—two friends, driving South, seeing things they’ve never seen, inviting their lives to change. Soon after, when Blinky applied to extend his Visa, he sent a glowing letter home: his work had benefited from his time in the U.S. and that his whole relationship to materials was changing. He would make Times of Day Number I, a series of small canvases that juxtaposed small bands of one color (blush pink, for instance) with a larger rectangle of another (like aqua green). Then, in 1976, he’d complete the epic To the People of New York City, a room of red, yellow, and black painting metal sheets. His final work would be bold, austere, and yet still surprisingly effortless, more forthright than Rothko, less industrial than De Maria. Meanwhile, Imi would begin to explore the more plastic aspects of color relationships.

When Blinky died of mysterious (a euphemism for “drug-related”) causes while vacationing in the Maldives, he left a just-beginning conversation unfinished. Imi continued one-sided, giving to someone who could no longer give back.

For Blinky represented a turning point for Imi. His more manicured approach to shapes and hues asserted itself for the first time, responding to the casualness of Blinky’s paintings but reflecting a wholly different way of seeing. The two had the same teachers, histories, influences and yet still spoke different languages. When Palermo’s retrospective visited LACMA this past fall (it opens at the Hirshhorn on February 24), Knoebel’s paintings were on view in the galleries upstairs. I didn’t yet know much about the artists’ friendship, but I immediately wanted to compare them, because Blinky made color look like a low-stakes experiment while Imi made it a careful operation.

It seems like an ideal, unnaturally democratic model for influence among friends: to share experiences, interests, and time and then render objects that reflect wholly different perspectives on what was shared.