For the past couple years, I have been teaching Bay Area-based artist Amy Balkin’s work within a curriculum about environmental art and “land expropriation.” I teach her work besides Karl Marx’s twenty-seventh chapter of Capital vol. 1, regarding “Expropriation of the Agricultural Population from the land” in 14th– throughout 19th-century Europe. I also teach her work alongside Robert Smithson’s writings on the planning and maintenance of Central Park in New York City, and Agnes Denes’s writings about her Wheatfield (1982) and Tree Mountain (1992-1996) remediation projects. These art writings/projects form obvious parallels with Balkin’s work, which has to do with land use, the creation of public space, as well as the legal, economic, political, and social problematic of positing a “global commons”—an international, public space that would be the property of all and none simultaneously. Which is to say, would be shared in common.

The speculative aspects of Balkin’s work are redolent both with science fiction narratives and historical utopias from a variety of different periods and cultural locations. The Paris Commune comes to mind, but so does Afro-Futurism, or the work of Samuel Delaney. The purpose of the speculative, as Balkin discusses below, is to project a reality that may become true if it is ardently worked towards. As such, what Balkin calls “counter-speculative spaces” model relationships and phenomena that one would want to have had. That, in other words, might create conditions of possibility whereby “global commons” might actually be able to exist in some way, shape, and form. Future conditional tenses abound in Balkin’s very future-directed projects, whereby the future enfolds multiple presents and vice versa.

Amy Balkin, "Public Smog" billboards, Douala, Cameroon 2009. Image: Benoît Mangin. Courtesy the artist.

While artists and thinkers have attempted to think through utopias alternative social, economic, and political realities for a long time, there are very few precedents that I can see for Balkin’s work in art history, a work which the poet and critical theorist Rob Halpern recognizes as one which takes as its “material” the law. What does it mean for the law to become a legal material?

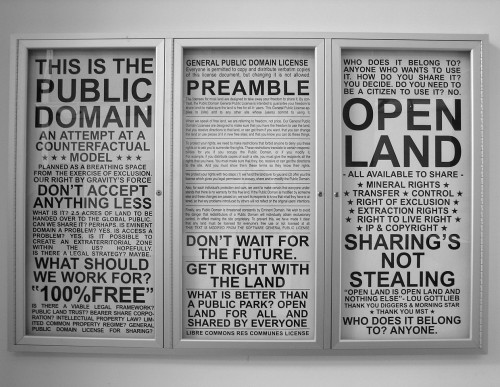

In two of Balkin’s most sustained and extensive works to date, This is the Public Domain (2003) and Public Smog (2006), what makes up the work is a paper trail of documents, actual, and virtual actions/performances, and research items that provide evidence for a practical exploration of legal and economic aporias; aporias which, when encountered through Balkin’s works, make visible the workings of a property system in the US (This is the Public Domain) and the current “carbon emissions trading” schemes made possible and lucrative by the Kyoto Treaty (Public Smog).

Through This is the Public Domain, Balkin makes visible the limits of “commons” in US law through her attempt to produce, via legal channels, the common ownership of a two and one-half acre plot of land. By doing so, Balkin reveals the very structure of the US legal system to work against commonly owned property. Likewise, in her attempt to make a “clean air park” in the atmosphere [first in 2004, in Southern California’s South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD), which is comprised of “all or portions of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties”; and for a second time over the European Union from 2006 through 2007], Balkin reveals how carbon emissions credits trading works (a mystery to me before I encountered her work), and to what extent this mirrors a process of “primitive accumulation” and “expropriation” throughout the history of European and now global capitalism. For, implicit in carbon emissions credits legislation is an open invitation for corporations to exploit a global atmosphere with limited regulation by national and international legal channels.

In Balkin’s booklet accompanying Public Smog, the various anomalies and aporias surrounding the recognition and enforcement of the atmosphere as a globally-recognized commons are foregrounded through a series of phone calls and letters Balkin undertakes to the UNESCO “world heritage foundation.” In her deliberate efforts to make the atmosphere a “world heritage site” (a site internationally marked for preservation), she reveals how the very structure of international law (represented by the flimsy mandate of UNESCO) undermines any legal attempt to enforce a global commons that would be in the interest of all people rather than corporate profit. In the process, Balkin also reveals the absurdity of notions of property in the face of global systems such as the ocean’s channels and the stratosphere, which are of course ecologically inextricable.

When teaching Balkin, it is my hope that one of my students—whether acting as an artist or in some other employment eventually—will take up Balkin’s aesthetic strategies, which reveal how various legal and economic structures currently work to ensure climate crisis, labor exploitation, and other errors accelerating the systematic erosion of patterns of well-being within a public sphere. Faced with Balkin’s work, the purpose of art as it has been articulated by art history has never been more questionable, where the problem of these works—as with many of the projects of other artists working within a history of environmental art—has to do with the scale of human endeavor and error with regards to a global ecology coextensive with cultural production.

In Robert Smithson’s “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape,” an essay Smithson published shortly before his death in 1973 in response to an exhibit of documents at the Whitney Museum about the planning and maintenance of Central Park, Smithson recognizes that art can no longer simply represent “nature,” but must become actively and critically involved in its making. In this way, the “industrialist” and the “artist” of Smithson’s time become dependent upon each other’s disciplines, their work.

Amy Balkin, "This is the Public Domain, Land Auction," Flash loop still, 2003-2011. Courtesy the artist.

Researching property law and corporate-governmental processes, Balkin extends Smithson’s art world provocations in fundamental and original ways. At the limits of her work, we can see the barriers that confront any legal-economic transformation of public space to include relations that are not ruled by property, and which do not involve the destruction of the ecosystem for “neoliberalism” — by which I mean recent capitalist economic phenomena supported through governmental policies of deregulation favoring the invested. But where the legal ends in Balkin’s work—where despair and failure come into site/sight—may be a place where other worlds appear before a social imagination. What if, legally and extra-legally, one were to work against the structures that dictate relations of “expropriation,” property relations which obstruct the erection and maintenance of a global commons as a proper end for social justice? Through a deliberate effort that is not afraid to get its hands dirty with bureaucracy, Balkin presents a whole new set of problems with which to work as an artist against the world as it is.

1. What is your background as an artist and how does this background inform and motivate your practice?

I studied painting, video, and sculpture in the early 90s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where I was introduced to the critical video work being made by groups like Paper Tiger Television. This kind of critical media art has influenced me since, although I don’t work in the same way.

After finishing school, I moved to San Francisco. When I first arrived, I volunteered at Artist’s Television Access, a community-run space that provided low-cost video editing, as well as screening a lot of video work that wouldn’t have otherwise been shown here. I also did a lot of traveling around California, taking trips to interview people about vernacular architecture for a ‘zine I was collaborating on, spending time at undeveloped rural hot springs, and visiting the kinds of places that you might associate with Matt Coolidge and the Center for Land Use Interpretation. The ‘zine, called Lackluster, which I made with James Harbison, often involved just showing up somewhere and seeing if someone was willing to talk to us about where we were, which most often people were willing to do. A lot of the places we visited, like Grandma Prisbrey’s Bottle Village in Simi Valley, or Nitt Witt Ridge in Cambria, didn’t get a lot of love at the time, and the builders or caretakers we met were often socially or politically isolated from their neighbors.

I eventually went to graduate school, where my work went from considering the human-modified landscape through sculptural installation, drawing, and video, to more directly addressing social relationships around land. At that time, I was thinking a lot about national parks and their aesthetics, and about the commodification of land in relation to a range of “evictions” that were happening locally and nationally, including the installation of anti-homeless street furniture in San Francisco, the attempt by the George Bush administration to use eminent domain to “take” land for oil pipeline network development, and a wave of literal property-bubble housing evictions around the Bay Area. Now, addressing spatial politics definitely motivates my ongoing work. But my background was first as a painter, so I carry that with me.

2. Do you feel there is a need for the work that you are doing given the larger field of visual art and the ways that aesthetic practices may be able to shape public space, civic responsibility, and political action? Why or why not?

I suppose I believe there’s a need for the work that I’m doing, even if the need is just my own – otherwise I’d be doing something else. But this is an ongoing historical question – if and how aesthetic/political practices can reshape public space and private property, if and how these practices are co-opted in their own moment or retroactively, and whether or not these types of practice are regressive rather than progressive, symbolizing change rather than effecting it.

Balkin and colleagues survey the "public domain." Amy Balkin, "This is the Public Domain," 2003-2011. Courtesy the artist.

Some of my work deals with constructing “speculative counter-spaces” I’d like to see, such as a permanent global commons (in the project This is the Public Domain), or a clean-air park (Public Smog) in real space. I’m sure I’m not alone in wanting more equitable relations globally around access to and control of land, water, and air. But there’s also a range of issues raised by these kinds of projects, including questions of dilettantism when addressing issues of expropriation. It’s easy to think of current examples of brutal struggle over land, including land grabs, occupation, and forced expulsions, so what are the relative stakes?

But Walter Benjamin had this to say – “One of the foremost tasks of art has always been the creation of a demand which could be fully satisfied only later” – and though he was speaking about future technological advancements that would allow for the production of new forms of art, I think it’s very helpful to consider, particularly in terms of the potential for positing counter-models in the context of aesthetic practice. And perhaps attempting to produce these spaces might move them further towards the realm of political possibility.

In these projects I’m prepared to – and can afford to – fail narratively and in material space, which can be a way to enter into the mechanisms that frame and define how land is distributed, used, and policed, particularly with regards to law and the commodity framework for “common-pool” resources. But the question of failure, considered differently, also points to the problem of artists choosing the field of aesthetic practice as an arena for action, which might or might not be capable of transforming space.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired your work? Please describe.

I’ve been heavily influenced by people, sites, and land movements outside of art practice, people like Lou Gottlieb of the 1960s folk group The Limeliters and his attempt to deed land he purchased for the Morning Star Commune to God via the California court system, movements like the Brazilian Landless Rural Workers Movement, or places like The Principality of Sealand.

While my own projects have been inspired by a range of influences, as I’ve worked on them, I’ve become familiar with a number of artist projects addressing land ownership, use, or sharing – including Maria Eichhorn’s Acquisition of a Plot of Land, N55’s Land, or Gordon Matta-Clark’s Fake Estates. These projects all share some level of concern about how land is divided and structured into property, and to greater or lesser degrees, how rights of ownership are acquired, used, or shared.

Maria Eichhorn, "Acquisition of a Plot of Land, Tibusstrasse, Corner of Breul," installation sculpture, Skulpture Projekt Munster, 1997.

Some artists whose work I’m drawn to include UK-based collaborative Platform, who produce counter-cartographical projects and do substantial writing on oil, the politics of pipeline development, siting and human rights issues; Stephen Willats‘s artwork and his writing on it in Art and Social Function; the utilization of institutional leverage by artist group WochenKlausur; and Sarah Lewison‘s projects, particularly her collaborative re-reading of the court transcript The People of the State of California vs. Louis Gottlieb, and her project about weather modification in China – on “precipitation enhancement and hail suppression.”

I’m also influenced by radical geographers like Don Mitchell, whistleblowers like Mark Klein, environmental justice and climate activists, and the speculative fiction of Philip K. Dick.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

As far as the production of “speculative counter-spaces” goes, I try to work in real space and consider some social mechanisms that define it — such as law, commerce, mapping, and state/police power. Two of my projects, This Is the Public Domain and Public Smog, attempt to create these types of counter-spaces, through efforts to create commons or parks – on land in the United States (This Is the Public Domain), and in the sky in various places above the Earth (Public Smog).

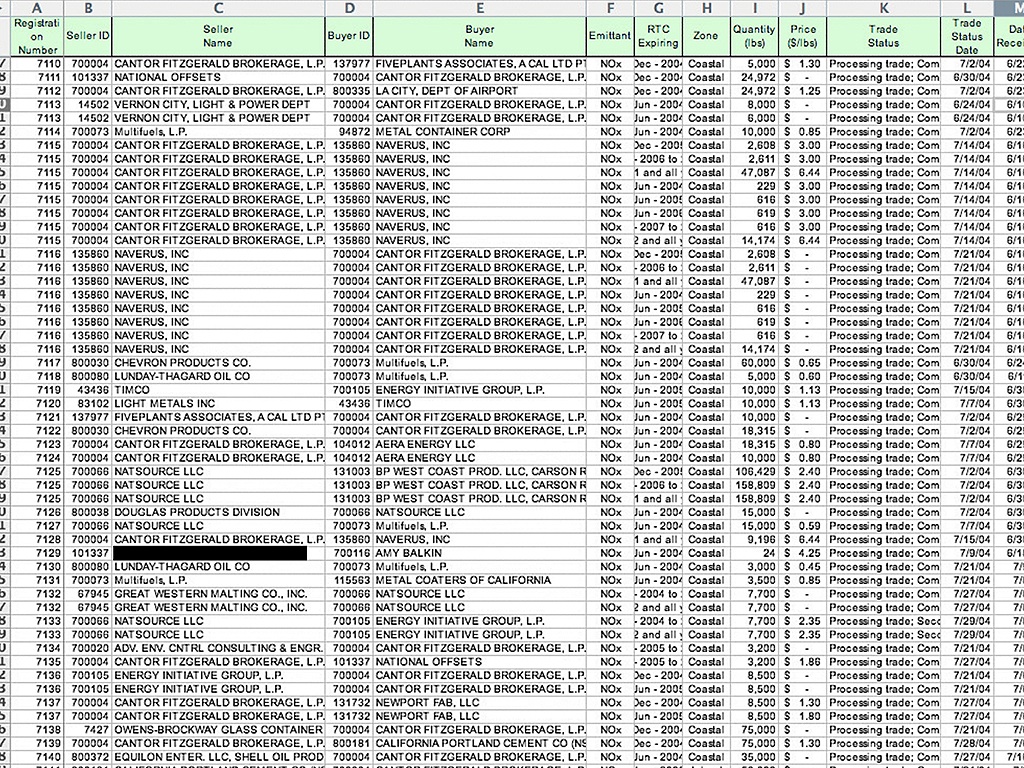

Both efforts involve first acquiring rights of ownership. In This Is the Public Domain, it meant attempting a range of strategies to acquire land with the intention of giving it to the global public as a permanent public commons. This included online requests for land donation, soliciting the San Francisco Archdiocese, inquiring at the Bureau of Land Management about the availability of free land, bidding at a foreclosed property auction, and bidding on eBay. I eventually bought two and a half acres of land for the project in a wind farm near rural Tehachapi, California, for just over a thousand dollars, through a “seller” I contacted on eBay. The mineral rights are still owned fractionally by the Bank of America and some individuals. In Public Smog, with help from brokers, emission traders, and others, I purchased rights to emit the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide and other smog-forming gases into the sky over the European Union and Southern California’s South Coast Air Quality Management District (which includes Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside Counties).

It’s relatively difficult for individuals to buy emissions credits in regulated markets (often requiring a permitting process) and easy to withhold these “rights” from use for their regulatory lifespan. It’s much easier to buy land, but (unsurprisingly) much more difficult to give it away to the global public – there’s no mechanism or loophole within the American legal system that I’ve been able to find so far to do so.

So these projects involve staking out a path until it reaches a point of (administrative, bureaucratic, social, economic) failure, and then reconsidering the tactics and strategy toward hopes of a successful outcome – which would be the public opening of a prefigurative space; by which I mean a functioning model that presents a place we might inhabit in a possible future, based on a different set of social relationships to how land, or water, or the atmosphere, is occupied and shared.

Although as projects engaged with bureaucracy, both can be frustrating, I’m continually interested in trying to strategize ways to bring theses spaces into existence, which makes them satisfying to work on over a relatively long period of time.

5. What projects would you like to work on in the future? What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

I see my work heading towards speculative exercises and objects that deal with spatial politics – and hopefully in directions I can’t predict.

Pingback: Tweets that mention 5 Questions (for Contemporary Practice) with Amy Balkin | Art21 Blog -- Topsy.com