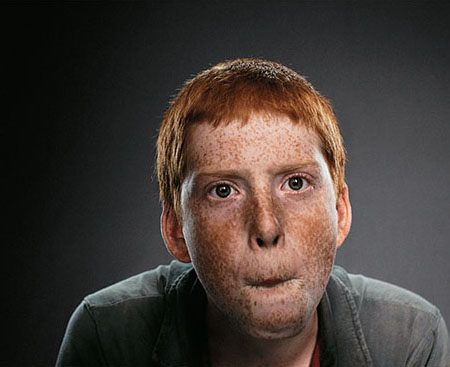

Image of a boy playing a video game from Robbie Cooper's "The Immersion Project"

Whether or not computer games are actually any good for us – some argue they cause children to become withdrawn and asocial, and others suggest that they provide valuable life skills, like killing zombies with flamethrowers – there are certain life lessons all of them, whatever they are, eventually teach. Namely: spend long enough doing something and you’ll eventually do well at it, then suddenly regret all the time you spent doing it. Or: there are some things you will never be able to do, no matter how hard you try. There’s nothing like a video game – especially when the avatar is the almost exact physical opposite of the player, which is all the time – to reinforce a deeply-rooted feeling of loserishness. And that, roughly, is the subject of Cory Arcangel’s outstanding new installation at the Curve gallery in the Barbican Centre, called Beat the Champ.

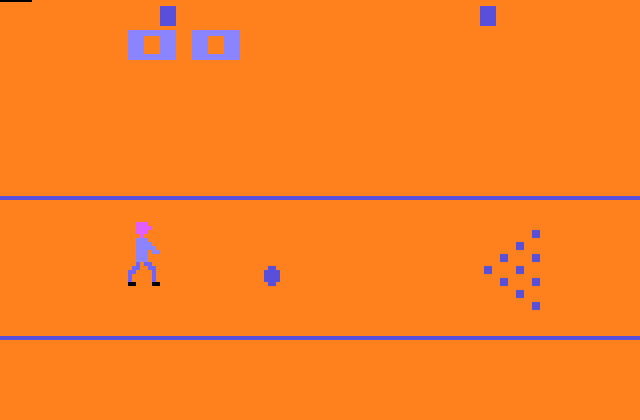

Cory Arcangel, "Beat the Champ" (2011) at Curve gallery, Barbican. Photograph: Felix Clay.

Initially, Beat the Champ, which consists of 14 chronologically ordered wall-size projected clips from ten-pin bowling games, looks like a kind of history of digital aesthetics, from the juddering Atari blocks of the first clip to the slick detailing of a recent PlayStation version. One of the pleasures the work affords is the indulgence in this teleological narrative, recalling a gallery of paintings from medieval to Renaissance to mannerism: realism replaces flatness, which is then replaced by willful superfluity, like an avatar’s Durstian soul patch or the reflection of digital bowling shoes in a shiny digital floor. In line with that analogy, there’s a point at which the image’s beauty peaks and topples and everything becomes garishly ugly, Second Life-style, where muscled arms turn cubist when they move and heads and necks are the same width. Each avatar in each game has been hacked to throw a single ball, which, depending on the iteration of the game, either shoots straight into the gutter or wobbles promisingly towards the crowd of pins before slinking off-center. The evolutionary aesthetics of the images are continually undercut by their inability to play the game. No matter how good it looks, in other words, it’s just one goddamn gutterball after another.

Arcangel’s piece doesn’t just trace the aesthetic development of the bowling game; it becomes a chart of video games’ emotional maturation, too. The whole piece reads as a parable of adolescence, and not just in its relationship to an archetypal teenage activity. The Atari bowling man, like a young child, is the least bothered by the disappointment of the gutterballs: he just jiggles back into place, indefatigably ready to keep pitching that little black hexagon (“Again! Again!”). The more recent you get, though – the more teenage – the more existentially troubled the avatar becomes, waving his cubist arms in the air like it’s Platoon, or clasping his cubist hands to his face in shattered disappointment, or (in the case of the Durstalike) manfully shaking his big frowning head side to side, speechless at the injustice of the world/his parents. He looks very sad.

Beat the Champ is, in a way, the video game equivalent of Christian Marclay’s The Clock (now on show in London, again, at the British Art Show at the Hayward Gallery). Both works sieve information from the world of images, and, by reconfiguring them in a way that runs contrary to their original context and function, draw attention to the way those images gave shape and form to our sense of ourselves. Arcangel’s installation loops moments from games that would ordinarily be waystations towards the game’s completion – and, thus, its obsolescence (for which, read “adulthood”). Marclay’s piece does something similar, isolating sections that provide the scaffolding for narrative momentum, without allowing that momentum to burn itself out. By locking these clips into a perpetual, Beckettian loop – and there really is something Krapp-like in those endlessly hopeful, endlessly thwarted avatars – Arcangel’s work allows for neither progression nor termination. You don’t get any better, but you don’t stop playing, either. Or, better: we are all in the gutter, and none of us are looking at the stars.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Letter from London: Gutter Rug | Art21 Blog -- Topsy.com