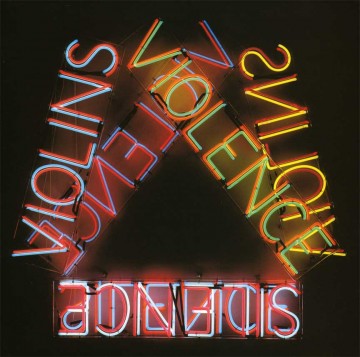

Bruce Nauman, "Violins Violence Silence," 1981-1982. Neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, 60 1/2 x 66 1/2 x 6 inches. Oliver-Hoffmann Family Collection, Chicago Courtesy Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, © Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Critic and teacher Kathryn Hixson is the one person I’ve had in my life who felt like a mentor in the deepest sense. She was wickedly funny, challenging, and yet warm. When she passed away this last fall, she left me feeling unmoored — I realized how very much I relied on her presence, her feedback.

A year ago, she helped curate a group show in Chicago, KILLING TIME, that I was fortunate to participate in. Next month, all of the artists involved are showing work together again. Kathryn’s last critical project was research into the role of comedic aggression in art; so we’ve decided to call the new exhibition NO JOKE.

In conjunction with the show, we will be holding a reading on Sunday April 10, of Kathryn’s writings. For this event, through the gracious generosity of Kathryn’s sister Irene Hixson Roderick, I was able to obtain some fragments of her research for what was to be her PhD dissertation (and, no doubt, a kickass book). The working title was It’s Not “Why?” but “How Long?”: Comedic Aggression in Visual Art of the 1970s. Here’s an excerpt from an early draft of her introduction:

Another consistency that emerges surprisingly is the almost universal interest in the human body: its presentation and representation in artworks. Andy Warhol’s Elvis and Carl Andre’s Lever may represent two poles of ways of dealing with the figure: Elvis is an image of an image of a Hollywood/music/TV icon, while Andre removes almost all materiality or image from the Lever to leave the viewer with his or her own body: its location, sensory input, spatial context. The events of 1968, the Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam, Woodstock, and feminist protest had, each in its own way, concentrated a hard focus on the human body as a site of protest, conflict, and as a powerful force in social space. Each individual’s real physical body was a site for action—drafted, danced, protested, de-brassiered, body-bagged. Each person’s body had the potential for social impact, in a riot, political rally, conscious-raising group, or concert hall. Across the arts, from Nauman’s stomping in the studio to Robbe-Grillet’s post-existential Realism, to Francois Truffaut’s auteurism to Kenneth Anger’s structuralist films, the human body in action (or not) is held under the tightest of scrutiny, and is critical to the content of the work. This presentation and representation of the body is fundamentally different from that of Abstract Expressionism that left a field of action with paint, or presented a chance to transcend the body. It is also a different type of ‘realism’: less the symbolic potential of AbEx or commodity embrace of Pop or severe existentialism of Minimalism. In the post-minimal feminist conceptual mélange of the 1970s is a new realism based on the lived body, not its imagined fiction. And it is this new realism that allows for the infusion of the media image as part and parcel of bodily reality.

During the 1970s, each of the aforementioned social forces worked on that body to focus, manipulate, and sell. Hippies and feminists developed visual styles. Fashion followed. Images of people on television, in magazines and newspapers, in the movies proliferated right along with each family’s photo-album pages, stacks of 35 mm color slides, and the body was soon image.

Within this engagement with the human body—as presence and/or image—artists consistently used the strategy of aggression toward the viewer/spectator/beholder in order to impress on his or her own body the specific point of a particular work. This situation follows the debates about the “theatrical presence” between Michael Fried’s criticism and the artist practices of the Minimalists, which itself follows the time-based participatory events of Happenings and Fluxus performances. But the 1970s saw a further parsing of this aggression, in both formal strategy and psychological content. The distinction is clear between Carl Andre graciously allowing us to tread on his metal tiles, and Bruce Nauman daring us to squeeze through the startlingly narrow space between his one-inside-the-other Double Steel Cage of 1974. And, as presentation of the body turns to its re-presentation as image, so too does artistic aggression turn to the shock of the image. Tortured clowns, suicidal swings, white-trash-soft-porn, and beaten-the-shit-out-of self portraits challenge the viewer, while punching emotional buttons, to understand the physical power of the image of a human being.

Viewers were willing to chart, or react, or succumb to this 70s artistic aggression through its strategic delivery through humor. The pun, uncanniness, slapstick, one-liners, and good old self-deprecation ranged through the art of the 1970s. It is as if the serious shadow/veil of post-war Abstraction, developed under the oppression of the recent tragedy of WWII, was allowed to lift a bit, or allowed to pass on into history. As Duchamp’s dry witticisms of the early 20th c. enjoyed a revival in the 1960s by artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, the charades of the Dadaist seemed to be embraced in the 1970s. Feminists felt compelled to perform ludicrous parodies of their femininity to make the pain of gender stereotyping obvious (e.g. the CUNT Cheerleaders of Womanhouse). Conceptualism’s literal evaporation into language and action, once more awarded the joke its old authority. (e.g. Robert Barry’s release of gasses into the atmosphere, Weiner’s instructions that need not be performed, and Piper’s odd street behaviors).

The strategy of comedic aggression in artwork in the 1970s has been oft noted, but never understood as a consistent stream that holds work of this decade together. Rather, specific examples of 70s art art used to suggest this aggression is what holds work by the various generations apart. I will attempt to track this stream as a continuity through roughly the decade, asserting that the 1970s started in 1968, and pretty much came to a close by 1985, though terribly influential in late 1980s, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. I will present this continuity by examining the 1970s work by four paradigmatic artists from two countries: Bruce Nauman (born 19xx) and Richard Prince (born 19xx) from the United States, and Rebecca Horn (born 19xx) and Martin Kippenberger (19xx-1993) of Germany.