I can go on my own to a museum or gallery or symposium, and I do, but going as a part of one of my classes makes me more appreciative of where (and what) I’ve chosen to study. London offers a bevy of opportunities for “in the field” study of art history, and the museums, galleries, and conferences of mainland Europe are just a cheap Eurostar or EasyJet ticket away. Plus, there’s something about going somewhere under the guise of a “field trip” that makes it that much more exciting. Hearing my professors’ and classmates’ thoughts outside of the impersonal setting of the classroom can energize my interest in a work I might have otherwise ignored or impart new perspective on something I may have been taking for granted.

In February, one of my courses went on a field trip to Paris. In three days, we went to at least twice as many museums, but that first day we only spent time at the Louvre. The eight miles of gallery space at the Louvre is a well-known fact, so you might imagine we’d look at a lot in five hours. However, I don’t think we looked at more than seven paintings as a group. We spent an hour in front of David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women, picking out the two-inch square that best represented the painting as a whole. The painting is a bustle of figures and activity, a not inconsiderable amount to take in and examine, but close consideration of the work really drew out its details in sharp relief.

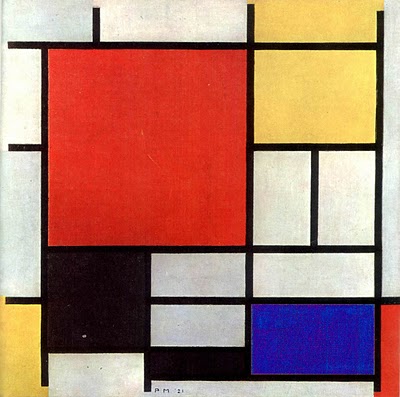

We spent two hours in one room of the Mondrian show at the Pompidou. How had I never noticed the little gaps and interruptions in the logic of Mondrian's grids before?

The exercise may sound fairly elementary – looking deeply and closely at a painting or any artwork for art historical study is a given – but I think it is an easy lesson to forget or neglect. Museum fatigue can sometimes make my visits to a large exhibition feel like I’m there as a hobby, that anything my glance hits can be haphazardly checked off some unwritten list of important things to see. Close looking, as my professor calls it, really encourages you to explore the artwork, question what it is, and not just take it at face value. It was another large chunk of time in front of Delacroix’s The Women of Algiers, before a friend spotted a watch amongst the chintz in the fictional harem, a surprise to everyone, including the professors who had discussed the painting throughout their careers. I began to wonder how much I might have missed in the past, how much I might never see in any one work.

During my spring recess this past month, I spent two weeks in New York, ostensibly to visit family and friends, but also to go to all the exhibitions I’d been reading about online from the other side of the Atlantic. I headed to the Whitney for the Glenn Ligon show, unexpectedly catching the tail end of the Edward Hopper show I’d assumed had already closed. I had planned for a leisurely afternoon with Ligon, but I felt obligated to see the Hopper while I could. The last-week crowds made some paintings a fight to see or spend time with, and I could feel my energy draining. The impulse to see it all is self-defeating – the harder I try to see every work I can, the less I actually get from what I see. I’ve known this for a while, but the struggle remains.

Remembering how much we saw in so few artworks while in Paris, I considered the possibility for more exhibitions of very small size, with as few as ten or even five paintings in total. Of course, it’s not practical, physically or financially, to regularly have so few works, especially in a major museum. A larger number of varied works can complement an exhibition with a specific narrative structure, and smaller exhibitions might also play down the role of the curator in the general public’s eye, contrary to the wave of star curating the art world’s been riding. Tourists have come to expect to see a plethora of art at the larger museums to get the most out of their increasingly expensive tickets. Smaller museums or less exhibitions of less renowned artists would struggle to compete with a big blockbuster single-work Picasso or Warhol show. The crowds would be even more obnoxious. Still, I think it’s worth encouraging, in order to get museum-goers to slow down and really savor the experience. The Brooklyn Museum’s current Lorna Simpson show is a good example of the “less is more” approach. A complex motif regarding collective memory is constructed in only three works. The vast array of collected photos in two of the pieces offers a lot to chew on, and viewers can take it in without being distracted by competing works.

Alain de Botton asked for a more inspiring museum experience, suggesting that making museums more church-like would be the answer. While I don’t necessarily agree with that idea, I do think facilitating more deliberately meditative experience with art would be beneficial, with an ethos similar to the idea of slow photography. A movement of slow art viewing, seeing less in order to see more.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubpRcZNJAnE]

More field-trips should be like this.

Pingback: MoMA | Five for Friday: The Picture Stays in the Picture

Pingback: Welcome & Introduction – arthistory1030