It’s complicated.

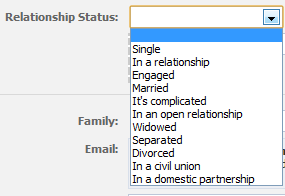

Last year, over 3 million Facebook users willingly adopted this dubious relationship status even after the drop-down menu expanded to accommodate eleven statuses, including newer options like civil union and domestic partnership.

Facebook relationship status options

This status is apt for those who want to publicly define the grey area that is his or her personal life, although its ambiguity may technically make it the only non-status, aside from simply hiding the option altogether. Tucked into the Basic Information page, the brief two (or rather, two and a half) words proclaim something like this: “I may or may not be formerly, presently, or subsequently interacting with one or more person(s) or thing(s) in a manner in which I define by the fact that I can not or choose not to define it!” In this sense, the complication evades categorization by problematizing, flaunting the complexity and ambiguity of a SimCity in fog. Although it may lurk ominously in the domain of relationships, the complication is also a creative force.

When unpacking sticky situations, one should not expect to discover anything less sticky. With appropriately viscous expectations, I (artist and guest blog alum, Lindsay Lawson) present Art21’s newest column, Problematic, aimed at diffusing, rather than shedding light on subjects that are particularly tricky, paradoxical, and well… problematic. The column borrows its name from friend and artist, Guthrie Lonergan, who suggested “Problematic” as an exhibition title, playing on its buzzword status that has become all too ubiquitous, peppering the rhetoric of art discourses. But everything is problematic if you look hard enough; you just have to will it so.

Consider Michael Asher’s infamous CalArts group critiques, in which a classful of furrowed brows might analyze a single artwork for eight hours or more. One can imagine their arguments being strung together word by word, formulated in real time, each utterance like a stepping stone toward some kind of ultimate point. Presumably the longer they looked, the more they saw; questions begat more questions and sometimes (maybe often), they arrived at equally valid yet incompatible observations. “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” says Charles Dickens. Those clever students must have occasionally found their panties in a paradoxical twist. At the very least, problems give us something to talk about.

Looking at art is invariably an act of interpretation influenced by context and perspective, but there can never be a single definitive reading. As one steps closer, the view shifts like the elusive end of the rainbow. It is an illusion that moves with respect to the viewer, a strange phenomenon of schizophrenic weather that appears only when conditions are simultaneously cloudy and sunny. Our slippery rainbow is neither here nor there, presenting itself differently to every person who looks up at the sky – the spectrum reflects a different angle for each grad student’s gaze. Similarly, a problematic artwork is a site of inconsistency in the best sense. One might imagine its true and definitive meaning buried deep in the leprechaun’s mythical pot of gold, both being equally elusive prizes. Even the leprechaun maintains a fluid identity: neither wholly good nor wholly evil; a miserly prankster, bearded fashionista, degenerate cobbler.

Lisa finds an impossible object at a garage sale in an episode of "The Simpsons"

Posts will focus on topics that are relevant to art discourses, while simultaneously occupying the foggier edges of logic. In a thematically related piece, I previously wrote about the various inconsistent recollections regarding John Wojtowicz’s 1972 attempted bank robbery in The Third Memory, a video by Pierre Huyghe. The work juxtaposes original news footage of the incident, excerpts of Dog Day Afternoon (a movie based on the true story), and Huyghe’s footage of Wojtowicz reenacting the event almost 30 years later in an ersatz bank set with stand-in extras. A paradox requires at least two incompatible, yet equally plausible components. Huyghe’s piece exposes a paradoxical gap: the greatest slippage of memory comes from the man who directly experienced the events in the first place. Our perception of time and space is riddled with such paradoxes. Memory harbors traces, gravity bends space and time, f@#king magnets (how do they work?). So if our understanding of art is indebted to our tangled perception, we have a lot of straightening out to do.

Problematic publishes on the first Tuesday of every month.

"Miracles" video by Insane Clown Posse