Bryan Crockett. "Gluttony," 2002. Cultured marble, 12 1/2 x 14 1/2 inches. Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery and Julian LaVerdiere.

Halfway through Night Scented Stock, an exhibition currently on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery’s uptown space in New York City, I found myself standing before an oversized, hairless (save for a few scraggly whiskers), baby pink mouse, whose fleshy body is covered almost entirely in large folds of fat. There is an unexpected pathos to this rotund little oddity nestled on its plinth with its legs tucked beneath its corpulent body and its eyes half opened. While appearing to be some grotesque mutant from science fiction, Bryan Crockett’s indolent creature is in fact rooted in scientific reality, a representation in cultured marble of a genetically engineered laboratory mouse that has been fitted with an obesity gene for medical research purposes.

Crockett’s quirky sculpture is titled Gluttony, and is part of a series in which the artist transposes the seven deadly sins into the realm of biotechnology, using representations of genetically engineered mice to personify the seven sins—a centuries-old set of moral standards and proscriptions against the instincts and urges of our psychical and physical selves. Although alluding to the moral fortifications erected by society against primal behavior and modern science’s extreme efforts to overcome the corporal realities and imperfections of the human body, Crockett’s mouse paradoxically remains corporeal, crude and excessive, and thus seems a fitting introduction to the themes and concerns underpinning Night Scented Stock. This is a show that foregrounds a range of artistic responses to the boundaries of aesthetic and social convention, and focuses on a number of artists who have articulated—or at least gesture to—a space outside established norms and limits by seeking out the fantastical, untidy and dream-like aspects in both the natural world and our inner selves.

Curated by Todd Levin, Night Scented Stock includes nearly one hundred works by some seventy artists. Spread over three floors, this sprawling exhibition, with asymmetrical and at times densely grouped arrangements of works, has the air of a 17th century cabinet of curiosities (an ambiance encouraged by the inclusion of a narwhal tusk, a taxidermied albino peacock, and many other unexpected objects). And yet, despite being comprised of works that span several centuries and a range of mediums and categories—or perhaps because of it— Night Scented Stock achieves an improbable coherency. Functioning as an archeology of the desublimated, this eclectic assortment of works mines a dizzying range of metaphysical themes and existential subjects, from pre-modern ruminations on the inherent tensions in the natural world—between order and chaos and the beautiful and the grotesque—to more contemporary preoccupations with unconscious desires and impulses, and untidy bodily realities and excesses. Among other things, this show proposes that across time and cultures the phantasmagoric, the nocturnal, the magical and the rapturous appear as intrinsically connected artistic responses to the repressive frames of convention—as signs of liberation from or rupture of the social sphere.

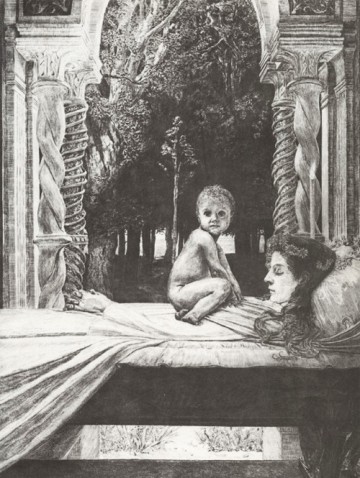

Max Klinger. "Tote Mutter," from the series Vom Tode II (On Death II), 1890. Etching and engraving, 21 3/4 x 14 1/4 inches. Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery and Peter J. Schwartz.

In many works on exhibit the macabre stands out as a central element of the fantastical and the hallucinatory, whether it be in Hans Balding’s The Witches woodcut from 1510 or the disfigured and truncated body parts of Michelle Oka Doner’s Tattooed Doll I (1968-2008). The macabre can also function as a form of rupture, as in Max Klinger’s 1890 Tote Mutter (Dead Mother), a small etching in which an infant stares out at the viewer from his position sitting atop his mother’s chest, who lies dead on a bier. Klinger’s is a startling image of a disturbingly ambiguous scene, one that seems devised to incite a strong emotional response while at the same time undermining any possibility of detached contemplation or resolution.

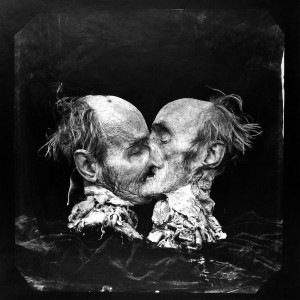

Joel-Peter Witkin, "The Kiss (Le Basier), New Mexico," 1982. Toned gelatin silver print, 14 5/8 x 14 3/4 inches. Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery and Silverstein Gallery.

In Joel-Peter Witkin’s photograph The Kiss (Le Baisier), New Mexico, the two halves of a severed and bisected human head appear to be embraced in a kiss. Simultaneously an image of life and death incarnate, the image oscillates between the poignant and obscene as the life-affirming and joyful associations of a kiss remain irreconcilable with the ghastliness of the detached and disfigured reality of the head no matter how long one looks at or thinks about it. The sublime power of Witkin’s photograph rests, as it did in Klinger’s etching, in the cognitive dissonance it produces in us as an inert body impossibly communicates profundities in an image that defies easy or stable conceptual resolution.

There are of course works on view that accede to the creative impulse of irresolution without resorting to the macabre, including Meshes of the Afternoon, Maya Deren’s highly influential avant-garde film from 1943. Filled with evocative symbolism and mysterious figures, Meshes of the Afternoon employs a non-narrative style and the radically innovative use of various cinematic techniques to give visual form to unconscious states of being, using rhythmic editing and other techniques to viscerally engage the viewer and blur the distinction between reverie and reality for both protagonist and spectator. In so doing, Deren, like so many artists in this exhibition, resists assigning definitive meanings to her imagery. Instead, her ethereal visual poetry becomes the very mesh of the film’s title: stripped of any clear cultural markers, it functions as a sort of cipher through which the viewer finds their own lyrical meanings and fills in the interstices with their own emotional responses. At its heart, this simple aspiration to have invention predominate over the invented reveals a deep desire to find emancipated spaces and deeper truths.

Maya Deren, "Meshes of the Afternoon," 1943. Film transferred to DVD. Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery, Tavia Ito, and Anthology Film Archives.

Night Scented Stock implies that this emancipatory impulse has been and continues to be expressed in visual culture through a variety of forms that range from the frivolous to the fantastic to the uncanny. This exhibition is at its best when the viewer that finds him- or herself standing before some strange and unusual object is able to abandon the need for definitive answers and yet still walk away sensing that they have glimpsed something significant. For me, Crockett’s quirky pink creature was certainly one of those objects, but in this teeming cabinet of curiosities, there are others to be discovered around every corner.

Night Scented Stock is on view until October 22 at Marianne Boesky Gallery’s uptown New York space, located at 118 East 64th Street, between Park and Lexington Avenues.