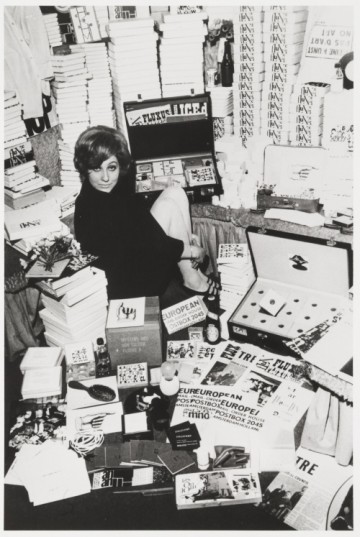

Willem de Ridder. European Mail-order Warehouse/Fluxshop. Winter 1964-65. Photo: Wim van der Linden/MAI. The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008.

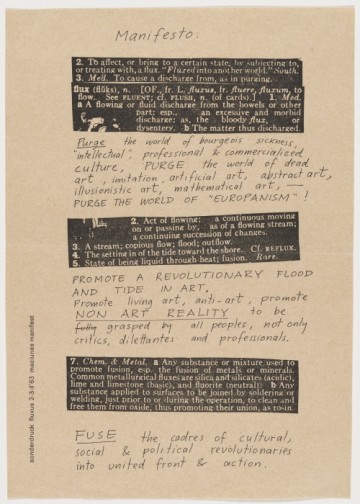

Fluxus, an international counter-culture collective of artists, musicians, and designers, was formed 50 years ago in 1961/2. Its goals were laid out in the 1963 offset lithograph Fluxus Manifesto (on view at The Museum of Modern Art), which denounces the “bourgeois” preciousness and exclusivity that surrounds art, promotes art “for all peoples,” and calls “cultural, social, and political revolutionaries to united front and action.” Fluxus artists and musicians–who hailed from all over the US, Europe, and Japan–felt that art should be affordable, participatory, and closely tied to everyday experience. In addition to artists who are known primarily for their involvement with this collective–such as George Maciunas, its founder and leader, Robert Filliou, and Ben Vautier (Ben)–a number of artists who began their careers as participants in Fluxus moved on to become influential in the wider scope of Contemporary art, including Christo, Nam Jun Paik, Deiter Roth, Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, and Claes Oldenburg.

“Fluxus Manifesto,” 1963. Offset lithograph. Edited, designed, and produced by George Maciunas. 8 3/16 x 5 11/16" (20.8 x 14.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008.

This fall, two survey exhibitions in New York celebrate the birth of this radical art movement: Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University through December 3; and Thing/Thought: Fluxus Editions, 1962-1978, at The Museum of Modern Art through January 16. The exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery, which was organized by the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, is accompanied by a scholarly catalogue and will travel to the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor early next year. In addition, a number of focus exhibitions are on view at university and non-profit galleries in the greater New York area. Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond in the Grey’s Lower Level Gallery and at/around/beyond: Fluxus at Rutgers, at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University (through April 1, 2012) highlight the significant role faculty members of both universities played in Fluxus. Artists Space, Creative Time, and the Staller Center for the Arts, Stony Brook University, are also all showing related work this fall. In keeping with the spirit of the movement, many of these exhibitions are supplemented by a roster of events, including gallery tours by the curators and artists, walking tours, performances, and panel discussions (please see exhibition websites for details). Finally, the biennial performance art festival Performa, November 11-13, will include a number of Fluxus events.

Fluxus was primarily about ideas, and the goal was to reach the largest possible audience. In a time before internet and email, prints and multiples in the form of artists’ books, ephemera, and mail art played an important role in disseminating the artists’ work, which were often group publications. They also organized festivals, participatory events, happenings, and performances, and created mail art, film, and unique works. Fluxus Editions were primarily produced and hand-assembled by Maciunas in unlimited editions and offered at low prices, distributed at artist-run Fluxshops or by mail-order. The first Fluxus group publication, An Anthology of Chance Operations…, 1961/3, (on view at The Grey Art Gallery), was compiled and edited by the Minimalist composer La Monte Young and designed by Maciunas. In 1962, Maciunas and Robert Watts came up with the idea of “an ever-expanding universe of events” (as quoted by curator Jacquelynn Baas in the introductory text at the Grey Art Gallery exhibition) that could be performed by anyone at any time. Open-ended and minimal instructions for specific actions using everyday objects, to be performed by a single person or by a group, were “composed” by Watts, Young, George Brecht, and others. These were mailed via postcard to colleagues, and a festival of performances was organized the following year, to take place throughout the month of May in the greater New York area. It was called “The Yam Festival” (May spelled in reverse). Maciunas also organized similar events throughout Europe, called Fluxfestivals.

“Fluxus 1,” 1964-65, Fluxus Edition announced 1962. Book with offset, metal bolts, and stamped ink, containing objects in various mediums, in wood box. Edited and assembled by George Maciunas. 23 1/2 x 22 1/2 x 4 1/2" (59.7 x 57.2 x 11.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008.

Later that year, Maciunas published Water Yam (on view at The Grey Art Gallery and MoMA), a boxed compilation of all of Brecht’s fluxscores, printed on small cards in uniform typeface. Instructions involved “turning water on or off, honking a car horn for a specified period of time, using decks of cards passed around by a group of performers, and other ordinary activities rendered extraordinary by having attention paid to them” (Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists’ Books [New York: Granary Books, 1995], 311). Shortly afterward, Maciunas announced that he would publish an annual Fluxus Year Box, a compilation of works by artists or musicians involved in the movement who wished to contribute, organized by geographical regions. The presentation of the work was designed and editioned by Maciunas and contained a wide variety of work in various formats, from printed matter to film to objects in multiple. Though he had planned to issue several of these, only two were published.

“Flux Year Box 2,” 1966. Five-compartment wooden box containing work by various artists. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, George Maciunas Memorial Collection: Purchased through the William S. Rubin Fund; GM.987.44.2.

Ben Vautier. “Total Art Match Box” from “Flux Year Box 2.” c. 1965. Box of matches and offset. The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008. © 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Individual artists also generated their own Fluxkits and editions, which were distributed in the same manner as all other Fluxus materials. These took a number of formats: artists’ books and multiples containing objects, event-scores, or records of events; chess sets; mock postage stamps; wallpaper; and concepts presented in a poster-like format. A number of examples are on view in each of the exhibitions; MoMA has invited six artists (some of whom were original members of Fluxus) to determine the arrangement of various Fluxkits over the course of their exhibition, two at a time. Each artist’s arrangement will be on view for a period of approximately three to four weeks.

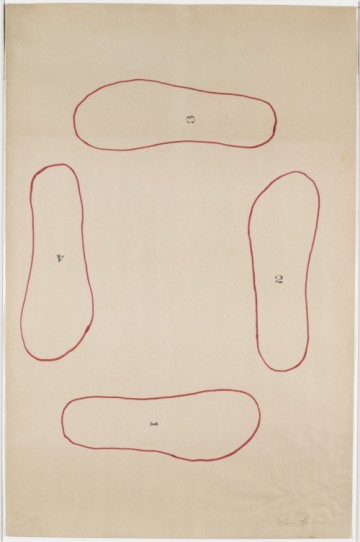

Benjamin Patterson. “Instruction No. 1,” 1964, Fluxus Edition announced 1964. Felt-tip pen and stamped ink on paper. 30 11/16 x 20" (78 x 50.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008.

Ephemeral printed materials were an important means of communication for Fluxus. Postcards and posters were printed to announce events and sent or displayed in public areas, respectively, and Maciunas edited a Fluxus newspaper that was published sporadically. These are perhaps the most plentiful of Fluxus materials and a number of examples are on view in each of the exhibitions.

As can be surmised, one of the greatest challenges to organizing a Fluxus exhibition is making sense of it all. Due to the wide reach of the movement, the divergent and frequently text-based modes of expression of its artists, and the various components of many of the objects, there is great potential for information overload. The two survey exhibitions at the Grey and MoMA take different approaches to this problem. Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life (Grey Art Gallery) is organized in thematic sections that highlight a number of fundamental questions of art and life: “Art (What’s it Good For)?;” “Change?;” “Death?;” “Health?;” “Love?;” etc. This is a purely curatorial construction–these issues did not play a part in the consciousness of Fluxus artists–but it is a helpful organizing principle that helps the viewer navigate the material. Culled from the Hood Museum of Art’s George Maciunas Memorial Collection, one of the most comprehensive collections of Fluxus material in the U.S., the exhibition includes a number of prints and multiples alongside work in other media, including films and a number of unique early works by important artists such as Alison Knowles and Nam Jun Paik. In spite of the large pool of material, the exhibition is selectively and thoughtfully curated by art historian Jacquelynn Baas and does not overwhelm. While a majority of the work is displayed in a satisfying manner, the installation of the Year Boxes and a number of the early Fluxkits leaves the viewer unfulfilled–a few tantalizing bits are taken out, but generally it is difficult to appreciate the contents in satisfying detail.

The MoMA exhibition was drawn from a daunting collection of over 8,000 objects donated in 2008 by collectors Gilbert and Lila Silverman. In contrast to the Grey Gallery installation, co-curators Gretchen Wagner (Assistant Curator, Department of Prints and Illustrated Books) and Jon Hendricks (Fluxus Consulting Curator) have lavished great attention on the early “signature projects,” in Wagner’s words (e-mail interview with the author). These include the Year Boxes and the first four individual artists’ multiples, which have been given the majority of one gallery space to themselves. For example, a display on one of the walls contains a spread of event scores from various editions that can be read individually, and multiple copies of Fluxus I are on view, open to different spreads. As previously noted, a handful of artists will be arranging selected boxes in changing configurations in a large display case at the center of the gallery. The second area of the exhibition highlights selected Fluxfilms by Joe Jones, Yoko Ono, and others, and Jones’ “music machines” (instruments). Finally, the third section investigates Fluxshops and Fluxus Mail-Order Warehouses, with a spectacular full-scale model that recreates Willem de Ridder’s warehouse in Amsterdam, based on a 1964-5 photograph (illustrated top). Other photographs documenting events/performances, most of which were taken by Maciunas, help the viewer place important Fluxus events in time and space. The exhibition is book-ended with full-wall installations of Brecht’s No Smoking wallpaper, which lends a powerful graphic punch to the experience. Overall, the MoMA installation rewards the careful viewer with satisfying detail, while providing more casual visitors with a handful of eye-popping displays that give a general sense of the carefree and anarchic impulse behind the movement.

George Brecht. “No Smoking,” c. 1973, Fluxus Edition announced 1963. Offset wallpaper, designed and produced by George Maciunas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. © 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Germany.

Maciunas died in 1978, and the money, time, labor, and psychological leadership he provided to Fluxus artists proved vital to the movement. Activity slowed considerably thereafter and many of the artists moved on to work independently. Fluxus had originally set out to enact a revolution in art, but unfortunately Maciunas never experienced the full impact of his work; during his lifetime, the appeal and audience were limited primarily to other artists. Fluxus is now recognized as the precursor to Mail Art, Conceptual Art, and Performance Art, and its impact on contemporary art as a whole is widespread. The reverent attitude and low-brow aesthetic of Fluxus continue to influence artists today, and likely will for years to come.

Editor’s note: Curator Jacquelynn Baas’ name was misspelled in the first iteration of this post. The error has now been corrected.

Pingback: Ink – The Birth of the Underground: Fluxus Editions / Art21 Blog « word pond