At St. Mark’s Church in New York City, the home of Danspace Project, Jeremy Wade performed fountain. With the house lights on, Wade stumbled along the carpeted edge of the church floor, describing in detail the interior architecture of the area where he stood. His nervous tone and dramatic gestures indicated an imminence of the holy, satirizing it with the mundane and sterile minutia of which the church is composed. Wade then invited the audience to come up to the altar and touch it with him, calling everyone “pilgrims,” after Annie Dillard’s book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.

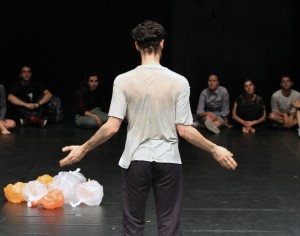

Jeremy Wade performing "fountain," 2011. Courtesy Danspace Project. Photo by Doro Tuch.

Wade then guided the audience to form a circle on the floor. What proceeded was a viscerally twisted exorcism consisting of choreographed writhing, groaning, torquing, guttural moans, whispered chants, and facial contortions. Wade made direct eye contact with the audience-cum-participants, suggesting that this is an exorcism for them, too, and that the dancer is channeling their demons. Having laid the space bare at the introduction of the performance, it was hard to decipher where the energy that fueled Wade’s act of channeling came from–whether it was an exorcism of his demons, those of the audience, or of historical demons in the context of the religious setting.

My experience in this circle was one of exchange, where as a witness I felt activated, as though my presence helped to fuel Wade’s evangelical endurance. The space of the church opened up for me. I became acutely aware of its structure, and how, when stripped of its symbolic codes, the church was just a place, empty and neutral.

Théodore Géricault. "The Raft of the Medusa," 1819. Oil on canvas.

Wade’s talent lies in his uncanny ability to draw attention and energy into himself, to the degree of absorbing all activity into an oscillating, chaotic world of movement and absolute terror. From a visual perspective, one might view his singular used-up, contorted figure as channeling the multitude of destitute bodies in Théodore Géricault’s 1819 painting Raft of the Medusa. For me, Wade’s performance also struck a cord with the beginning of the Occupy Wall Street protests, and the pain, desperation, anger and wailing suffered by those who desire change, as protesters congregate to perform direct actions with a strange mix of guerilla practices and what could be deemed an almost-religious hope for salvation.

Occupy Wall Street march to Times Square, October 15, 2011. Photo by Yoni Goldstein.

The following week found me at Prelude 11, the CUNY Graduate Center’s annual performance festival curated by Claire Bishop, Frank Hentschker, Rob Marcato, and Helen Shaw. The festival lasted for three days and included performances, readings, panels and lectures that ran throughout the day and night. Among the more transgressive works shown were Untitled Feminist Show, directed by Young Jean Lee, and Dick’s Jokes, performed by Donelle Woolford, both of which problematized the power structures of performance presentation.

Young Jean Lee's "Untitled Feminist Show." Photo by Blaine Davis.

To begin to describe Untitled Feminist Show is to decipher a complex and directly confrontational viewing experience that felt at once inclusive and open, playful and cunning, ironic and brutal. The performance was a 20 minute excerpt from a work-in-progress that will premiere in January at the Walker Art Center. Questionnaires containing multiple-choice questions were distributed to audience members, to be answered during breaks between the piece’s six segments. Six nude performers walked onto the stage and began a slow movement, where each emerged from the cluster of bodies and took their own space on stage.

Why did I just describe them as performers?

I would say that at face value, I saw six women on stage. But, as per the question that was asked of the audience following that movement–“Are all these performers women?”–I hesitate to generalize. Although I thought that I was witnessing female forms, I realized that I didn’t actually know how any of the performers identified themselves, and I couldn’t assume that my seeing them all as women was appropriate, or even necessary.

This experience spoke to the piece as a whole. As soon as a performer would use a clearly-defined gesture, action, dance, facial expression, or physical position, a question would arise that would throw off any certain definition of gendered behavior or interpretation. As disorienting as the performance was, it also generated an important question regarding the place of feminism in the 21st century, where it seems we may need to re-evaluate what defines gender identity, gendered behavior, and gendered expectations.

What would happen if we began to question the victimhood that has become a trope of feminist rhetoric and spoke truth to power differently? According to Young Jean Lee’s work-in-progress, the alternative is not to make any assumptions, and to define subjectivity moment by moment, to experiment with notions of all kinds of power, broadening out from the perpetuity of “fuck the patriarchy” into “fuck holding onto the idea of patriarchy.”

Donelle Woolford performing as Richard Pryor at Prelude 11. Photo by Irina Rozovsky.

Equally disorienting is the performance personae of Donelle Woolford, which is in turn part of an ongoing project by artist Joe Scanlan. Woolford is a visual artist whose role has been played by at least four different Black female actors, who study how to portray her from Scanlan’s direction. At Prelude 11, Dick’s Jokes was presented as the artist’s turn to comedy as a remedy for her disappointment about her current position. In it, Woolford re-performed the second-to-last episode of Richard Pryor’s short-lived Richard Pryor Show in 1977.

After taking the podium, the mustached Woolford-as-Pryor, angry because his show was just cut, began ranting about ABC Network’s racist ideology. There were a few interruptions from the “tech assistant,” performed by Scanlan. She then takes on Pryor’s character Mudbone, an old Black man from the South from whom Pryor claimed to have learned old stories. This is where the evening’s theme, “Extreme Appropriation,” reached the furthest end of extreme, as a Black female actor portrayed an artist portraying a comedian portraying an old man. Of course, as per Richard Pryor’s signature language content, there were plenty of “nigger” bombs and “motherfuckers.” At one point, Woolford made eye contact with a woman in the audience who appeared to be squirming and said, “Hey, hi you, can’t take your eyes off the nigga, can you?” “Hey folks, it’s true, she can’t take her eyes off the nigga!”

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?&v=Q8EM9MgO4FE]

It was awkward, hilarious and every kind of wrong, but as a work of deconstruction, it was perfect. The actor played the part of the antagonistic Pryor, while the hapless audience member played the unsuspecting victim sitting in the seat of white privilege. For at least 30 minutes we were all held somewhere between reenacting the role of an ABC studio audience in 1977, and being an art audience sitting in a gallery in 2011. Woolford provided a window into a moment within the history of civil rights activism, where censorship squashed the possibility of real confrontation. She also provided a mirror for the art world, which purports to be inclusive in theory, yet has historically failed to demonstrate this in action.

Pingback: Gimme Shelter | Exorcising the Post-Democratic Body - 1-954-270-7404