Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven is an artist based in Antwerp, Belgium. Her work is currently being featured in a solo exhibition, In a Saturnian World, at the Renaissance Society (on view through December 18). The exhibition includes an interactive animation along with numerous works on paper and digitally-produced prints. Her mixed media works often include images from vintage soft pornography magazines along with excerpts of text and bright, bold planes of color. Her works point to the contemporary issues around technology and sexuality while sourcing material from the past.

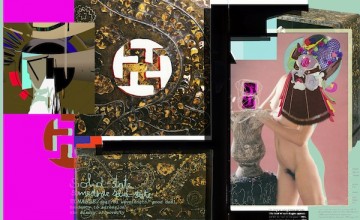

Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven. "Some Other Solid State," 2011. Digital Collage, 48.5 x 79 inches. From the series Mastering The Horizon. Courtesy The Renaissance Society.

In viewing van Kerckhoven’s works, it is clear that texts play a significant role in their conceptualization, as well as have a presence in the final object; however, these texts are not often the same. When I ask van Kerckhoven about her process and how texts play into her thinking, she tells me about how strongly the written word has influenced her from the time she was a young child listening to her grandmother’s fairy tales. Her continuing interest in linguistics began when a young, male ingénue, Luc Steels, began telling her about his research while she was a student herself, and the interest is stirred each time she travels to a new place. She tells me that her first exposure to a naked human body was through viewing an image from a concentration camp, spurring her to read the works of the Marquis de Sade. Here, van Kerckhoven tells me of how she began making objects:

In 1976, I was studying texts and was working in a Plexiglas factory. I started writing all these things on plexi sheets and gave them to young scientists I knew as presents. The first shows that I did were in bookshops, because I could not make exhibitions in other places. In those times, it was absolutely not done that you could exhibit just text on the walls as art. The first show I ever did with these works was in Amsterdam in a bookstore run by an American woman. It was in the back of the bookshop, which only sold Fluxus free-press. You have to see my work from that perspective–Fluxus free-press, mail-art. That is really my origin and why texts at all levels have such an importance for me.

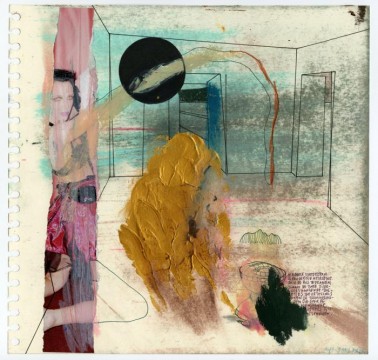

Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven. Installation view of "In a Saturnian World" at The Renaissance Society, Chicago.

The following is Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven’s reading list:

Olaf Breidbach, Neue Wissensordnungen. Wie aus Informationen und Nachrichten kulturelles Wissen entstheht. [New orders of knowledge. How out of information and messages arise new cultural knowledge.] (2008)

Mathias Frisch, Inconsistency, Asymmetry and Non-locality: a philosophical investigation on classical electrodynamics (2005)

David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave (2002)

Thomas Owens, Bebop: The music and its players (1995)

E.F. Schumacher, A guide for the Perplexed (1977)

Dr. Kwee Swan-Liat, Denken met de rechterhand [Thinking with the Right Hand] (1966)

Oskar Van Der Hallen, Het diabolisme in de hedendaagse roman [Diabolism in the contemporary novel] (1962)

Paul Verlaine, Poèmes Saturniens (1866)

I had the pleasure of speaking to Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven via Skype about her reading list. Our conversation focused on her ideas about the origins of art and language, and the role of the artist.

Kelly Huang: I found that many texts in your reading list address the ways in which new forms develop–whether in nature, the building of knowledge, or through the hand. How do you view the role of an artist? You talked a little about how you feel you were just born as an artist. What do you see as the artist’s role? Is it just as a maker? Is the artist a change agent?

Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven: Yes, of course. I have been writing a lot about it, also. I think it is very good what you said there, the artist as a change agent. I think it was Nietzsche that said in a sane society, there are no artists. Then, at the same time, I am completely convinced that at the origin of humanity, there was no difference between being a human and being an artist. I think the original state of being is being an artist. That is really of course, the difference between us and animals. Everything else is the same. This is also why I am still reading the book, The Mind in the Cave. This speaks to the origins of art having to do with abstraction and fear. It is also my conviction that abstract art as we know it officially has been something that belongs to men. Actually, abstract art has always been the domain of women artists. There is a curator here in Antwerp who did the exhibition Azetta: l’art des femmes berbères 10 years ago in Brussels about abstraction in the carpets made by Berber women. He said that women have been making abstract art from the beginning of art history. Of course it has to do with shamanistic imagery, which of course has to do with what is innate in us. Of course, you can see this in every society that is a little bigger than a family–at a certain point, there is a shaman. This has to do with the complex ways humans behave, and when there are problems, there are people who step up and take some responsibility out of the normal. It used to be through spiritual travels from which they come back and give answers.

KH: They try to breed understanding of these very abstract and hard-to-grasp ideas. There is this really great quote from The Mind in the Cave, that says “the very act of painting, assisted in the recall, recreation, and reification of otherwise transient glimpses of spiritual things.” I thought that was very powerful—this idea that the translation of very abstract ideas into a physical painting on the walls of a cave can help people try and grasp something they do not have answers to at that moment.

AMVK: Yes, and I am going to add to that. On one hand it is abstraction, you have the knowledge, the spirit. On the other, you have the body. A few years ago, I did a residency in Shanghai. I tried to understand, write and speak one sign per day. After 15 days, I understood how a Chinese person’s relationship between his body, mind, and language. It is different from the western angle.

KH: Linguistics is interesting because it gives one insight into how a person, from the time a person is born, begins to build knowledge and an understanding or perspective on the world.

AMVK: Last week, I did a workshop in a women’s prison in France. We had very nice oily pastels and soft pastels. It took just 15 minutes before I realized they were painting their faces with the materials. It is difficult to get hold on makeup in the prison. But, it is very weird because, at the very same moment last weekend, I was reading in a Dutch newspaper that the oldest paint box of mankind, 100,000 years old, had been found recently, but they did not know if it was a paint box or a box of materials to paint their bodies with. Artists inherited these traditions, and at some point, someone took the paint for the body and decided to put it onto a wall. The third element that is also very interesting is with aboriginal art. The rock on which you see an image is not the art, but the place in which you view it is sacred. Artists, we see things and create things, and we tell people to look at that.

KH: Paul Verlaine’s Poemes Saturniens was clearly very influential to your work in your solo show at The Renaissance Society, as the exhibition’s title “In a Saturnian World” is drawn from it. What was it about this collection of poems that inspired you the most—the prose? The subject matter? The rhythms?

AMVK: It was the fact that it was about Saturn, of course, and secondly, the introduction by Verlaine to his bundle. I took the whole introduction, in five pieces, which I used to finish this exhibition. I have known Verlaine and his work a long time, but it was the content of this introduction that struck me some months ago. This helped me to finish the decisive series of drawings that I started in 2008 and that deals with relevance and irrelevance. Saturn is this very colorful, enigmatic, very far, gas giant. It is one of the most beautiful things you can imagine. It’s at the end of the solar system, in the blackness of the cosmos. I have always been intrigued by this planet but from around 2000, Saturn is all over with razorsharp images in popular culture—National Geographic, children’s books, and high fashion magazines. Last May, I learned of the booklet by Verlaine and I was nailed down by it. I started reading the introduction and that is where I stopped, as it was already enough for me. I made it a point to finish and explain why I used these images of Saturn on some rather perverse, trendy fashion-imagery, and beautiful young people. I wrote something that made Hamza [Walker, Director of Education and Associate Curator of The Renaissance Society] really laugh, because he was convinced I wrote it because of jet lag. With this whole Saturnian thing, “I turned sleaze into an object of study and contemplation by changing its attraction into abstraction.” What attracted me to the introduction were the despair and the resignated attitude in which Verlaine deals with it–his acceptance of the relationships between evil, beauty, despair, and fate.