Fence art at Greenham Common Peace Camp, 1980s. Photo by Sigrid Møller, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

As I write this, it is almost four weeks since the raid on Occupy LA. I readily admit I was attached to the encampment—although I was a non-resident Occupier, I valued the site as a physical marker of not only my dissatisfaction with the status quo but also of the fact that a number of people believe things can actually change. “There it is,” said people walking, driving, riding, flying by the hundreds of tents pitched around City Hall from October 1 to November 30. Here resided the discontent, the protest, the idea. If you missed it one day, you could come back the next.

Embodiment is a concept that’s very important to my art practice and, subsequently, the way I live my life. I move between materiality and the relational, sometimes within a collaborative social practice, and other times when making objects. Language is always present in some way.

The space of protest is distinctive, with some objectives that are vastly different than those of art. However, many artists in Los Angeles and across the country have engaged with the Occupy movement not just as activists but as artists. I was compelled to do so because my art training has sensitized me to the need for any new vision to acknowledge the body.

What’s distinctive about Occupy in its first stages is that it brings the vulnerability of bodies to the fore in such a way that it becomes harder to look away. Occupy is an example of activism that brings the domestic into the space of the political or, rather, acknowledges that it’s been there all the time. Sometimes, for instance in the case of housing issues, this strategy of address seems natural. Around other issues, however, it’s effective not because it’s thematically directly linked, but rather its implication of protesters’ bodies in a durational fashion creates a sense of urgency and crisis.

Judith Butler spoke to this issue when discussing the strategies of the Tahrir Square protests in a speech she gave over the summer: “The bodies acted in concert, but they also slept in public, and in both these modalities, they were both vulnerable and demanding, giving political and spatial organization to elementary bodily needs. In this way, they formed themselves into images to be projected to all of who watched, petitioning us to receive and respond, and so to enlist media coverage that would refuse to let the event be covered over or to slip away.”

The aesthetics of Occupy encampments are very strong. Anyone who’s followed the news this fall would have a strong image of ragtag tents crowded up against each other, weathered campers standing defiant and fatigued, and, especially from the New York coverage, piles of trash spilling up and over curbs. To some these aesthetics are off-putting and support the assertions by some city governments that the temporary communities are unhygienic, etc. This was the public justification offered by the city governments of both Los Angeles and New York for raiding the Occupy encampments.

Inspired by the embodied strategies of Occupy, I’ve done some lateral research into other protest moments that don’t deny the corporeal and overtly involve the caring for of humans. Some are encampments, with varying degrees of the so-called squalor that comes when humans take up residence somewhere durationally, while some employ more specific aspects of daily life—dress, conversation, and elimination—in their strategies. I offer these examples as an opportunity to recalibrate our eyes. I want to remember our other senses that might allow us to respond to proposals for change critically, with compassion and/or empathy rather than disgust.

Fuchsia tents at Nickelsville camp, Seattle, 2008. Photo by Michaelann Bewsee.

Nickelsville camp in Seattle was started by Veterans for Peace in 2008. It’s named after the city’s mayor at the time, Greg Nickels, who passed an ordinance essentially forbidding homeless people to sleep anywhere on public property. Since its inception, the encampment has undergone fierce scrutiny by the city, forcing it to move sites 15 times. Now back at its original location and with a promise from the current mayor to let it stand, what began as150 fuchsia tents currently houses around 1,000 people.

The community is in the tradition of tent cities throughout history, which serve to house people during economic depressions and after catastrophes. The aestheticization of Nickelsville in its early stages served to highlight that it was an intentional community with organization and resources, perhaps making it less threatening in the eyes of the city. It didn’t work! But the encampment survives.

Tent action by The Children of Don Quixote, Paris 2006. Photo from lesenfantsdedonquichotte.com.

Another highly aestheticized tent protest took place late in 2006 in Paris. The Children of Don Quixote group pitched 300 tents along a city canal, in which protesters of many different economic means slept for the duration of the relatively short action, three weeks from beginning to end. In response to the protest, President Chirac agreed to provide housing placement for 120,000 people by 2012.

While up, the tents housed many citizens without homes as well as some people with homes who camped in solidarity. Each structure clearly represented another person not provided for within the French housing system. Although the tents did provide shelter, this action was less about creating an organic community and more geared toward providing an undeniable visual tally of those in need.

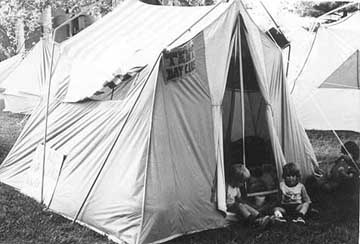

Protest encampment at Kent State University, 1977. Photo by Jim Huebner.

Young protesters at the Kent State tents, 1977. Photo by Barry Seybert.

In 1977, Kent State students protested in an effort to stop a proposed new gymnasium annex from being built on top of the site of the 1970 shooting of peaceful student demonstrators. This campus tent city was sustained for 60 days and was part of a two-year, multi-stage protest. Eventually the gym annex was built on the site.

The quid pro quo of protesters implicating their bodies in tribute to the slain students seems to me a perfect statement. Bodies taking up space in order to stand in for bodies that have become invisible.

The dummy Pyramid stage, Greenham Womens Peace Camp festival 1981. Photo © Justin Warman.

Protesters at the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, 1980s.

Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp ran from 1981 until 2000 and was the site of many anti-nuclear actions over the 19-year period, some of which involved 50,000 women at once. Some protesters lived there; the U.K. National Archives contains a description of Greenham’s infrastructure: “The ‘camp’ itself consisted of nine smaller camps: the first was Yellow Gate, established the month after Women for Peace on Earth reached the airbase; others established in 1983 were Green Gate, the nearest to the silos, and the only entirely exclusive women-only camp at all times, the others accepting male visitors during the day; Turquoise Gate; Blue Gate with its new age focus; Pedestrian Gate; Indigo Gate; Violet Gate identified as being religiously focused; Red Gate known as the artists gate; and Orange Gate. A central core of women lived either full-time or for stretches of time at any one of the gate camps with others staying for various lengths of time.”

The sub-camps reveal a protest designed around pleasure and preference. The Peace Campers created a protest space that was productive for them and sustained it for almost two decades.

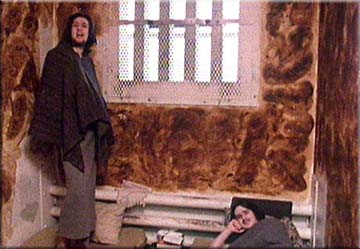

Political prisoners during a Dirty Protest and Blanket Protest, Northern Ireland,1979.

The “dirty protests” and “blanket protests” in Irish prisons in the mid-1970s were in response to a change in prison policy so that political prisoners were no longer recognized as a special category with more privileges than the rest of the prison population. Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) members who were part of the dirty protests refused to leave their cells for them to be cleaned, and eventually smeared the accumulated feces all over the walls. Living this way for weeks and months at a time, the prisoners’ self-inflicted inhumane conditions served as a hyperbolic register of their dissatisfaction with the prison’s infrastructure. In the blanket protests the inmates refused to wear the prison-issued uniforms, which meant they dressed in the only other garments available—blankets.

Encamped anti-nuclear protesters, Germany, 2011. Photo by Reuters.

Local farmers turned out a flock of sheep to block the passage of the trucks. Photo by RUVR/EPA.

Anti-nuclear protests in Northern Germany have been going on for years, in particular around the town of Gorleben, where there is a dumping site for waste. In November of 2011, there was a concentrated effort, with an encampment of humans blocking one of the roads used by trucks hauling waste. In solidarity, a farmer let out hundreds of his sheep to block the road so trucks carrying the waste couldn’t pass through there, either.

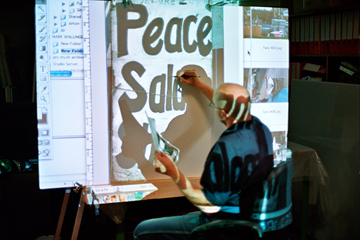

Brian Haw's camp outside British Parliament. Photo by Haris Artemis.

The art world is familiar with Brian Haw’s peace camp because Turner Prize winner Mark Wallinger’s piece, State Britain (2007), recreated the camp in its entirety including all associated signs, many of which were donated to Haw by the public. Begun in the summer of 2001, Haw’s ”protest for peace,” as he preferred to call it, was situated outside of Parliament in London. The government tolerated him for about ten years.

One of Mark Wallinger’s studio assistants recreates a protest sign from Haw’s camp for State Britain (2007). Photo by Michelle Sadgrove at Mike Smith Studio.

I think of Haw as, essentially, having been “in residence” in his small encampment for those several years. The site became a tourist attraction known all over the world. People could drop in at his home and visit, having some sort of personal exchange around political issues. A durational and conversational teach-in, Haw’s sustained physical presence allowed for thousands to experience his ideas, most from directly engaging with Haw or one of his supporters.

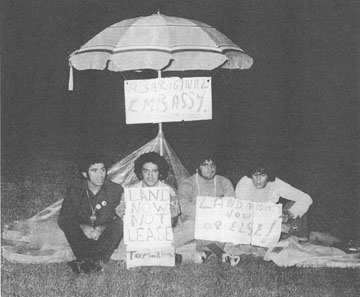

Alan Sharpley, Bob Perry and John Newfong at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra. Source: Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia.

Angered at the federal government's Australia Day statement rejecting aboriginal land rights, these four men drove from Sydney to Canberra to set up their protest under a beach umbrella. Source: Tribune/SEARCH Foundation, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

The Tent Embassy in Canberra, Australia was started in 1972 to call attention to the various issues within the country’s indigenous population. Originally the camp occupied lawns across from the parliament building, but has sprung up in other sites after being evicted numerous times. It continues in various incarnations to this day, although the protest’s original demands were not met at the time. They included:

• Control of the Northern Territory as a State within the Commonwealth of Australia; the parliament in the Northern Territory to be predominantly Aboriginal with title and mining rights to all land within the Territory.

• Legal title and mining rights to all other presently existing reserve lands and settlements throughout Australia.

• The preservation of all sacred sites throughout Australia.

• Legal title and mining rights to areas in and around all Australian capital cities.

• Compensation money for lands not returnable to take the form of a down-payment of six billion dollars and an annual percentage of the gross national income.

Books holding ground at UC Berkley, November 2011.

The last image of this exercise in lateral (horizontal!) research shows the “tented” books that appeared in Berkeley, California after the University’s Occupy encampment was evicted. The domestic scale of the books speaks volumes about the now missing architecture and the protesting bodies it once housed. This action perfectly highlights the Occupy sentiment that “you can’t arrest/evict an idea,” and that the movement’s infrastructure is constructed around a body of knowledge that’s been internalized by subjective bodies that can gather, exchange, disperse, and repeat the cycle the next day, and the next, and the next. This is the promise of protest, and, increasingly, all art concerned with social dynamics and the multiplicity of voices.

Anna Mayer moves between between collectivity and introspection in an attempt to establish an “outcantatory” practice that uses language, fire, and intention to propose relationships encouraging embodiment and the rejection of discreet, linear modes of reception. In addition to her solo practice, Anna works with Jemima Wyman as part of the collaborative duo CamLab.

Pingback: #OccupyArt21 | AAAAAA

Pingback: DisconTENT: Inside the Margins – MAAS Magazine