Michael Rakowitz. "Enemy Kitchen," 2004-present. Courtesy the artist. Photo: San Francisco Chronicle/Paul Chinn.

Michael Rakowitz made media headlines in December when U.S. marshals seized a critical part of his culinary project Spoils: the dinner plates. As it turned out, the elegant black and gold trimmed tableware, purchased on eBay, had been looted from the former palace of Saddam Hussein. Now repatriated, the artist has created a set of limited-edition paper plate replicas that accompanied the launch of his latest food endeavor, Enemy Kitchen (Food Truck), an Iraqi eatery on wheels.

Commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art for their exhibition Feast: Radical Hospitality in Contemporary Art, Rakowitz’s food truck is the newest iteration of his ongoing project Enemy Kitchen wherein he invites people to help him cook a meal based on the recipes of his Iraqi-Jewish mother. The conversation that takes place over the course of the event is perhaps more significant than the food that gets made. The artist notes, “On one occasion, a student walked in and said, ‘Why are we making this nasty food? They (the Iraqis) blow up our soldiers every day and they knocked down the Twin Towers.’ One student corrected her and said, ‘The Iraqis didn’t destroy the Twin Towers, bin Laden did.’ Another said, ‘It wasn’t bin Laden, it was our government.’”

With Enemy Kitchen (Food Truck) Rakowitz extends the possibility for dialogue and debate to the neighborhoods of Chicago. Every Sunday and Monday throughout Feast the artist and his rotating staff of local Iraqi cooks (who prepare the food) and Iraq War veterans (who act as sous chefs and servers) will be cruising the city in search of hungry customers. Following are excerpts from a recent interview with Rakowitz in which he discusses his goals and overall relationship to food.*

Nicole J. Caruth: What prompted you to make Enemy Kitchen mobile?

Michael Rakowitz: It was one of the extensions that had always existed in my mind after the variant that I started in New York and then produced in different places across the country. I thought about some of the things that had been so dynamic and exciting for me as it pertained to Return, which was another project I did with Creative Time, where I imported Iraqi dates and operated a storefront. What was really great about that was, for the few months that the project was up and running, it was an excellent hub where conversation could happen and also a place where New York’s really small Iraqi population could convene with some regularity. I really enjoyed that. It was where my interest in urban space and interventionism could intersect with my love of story telling and conversation.

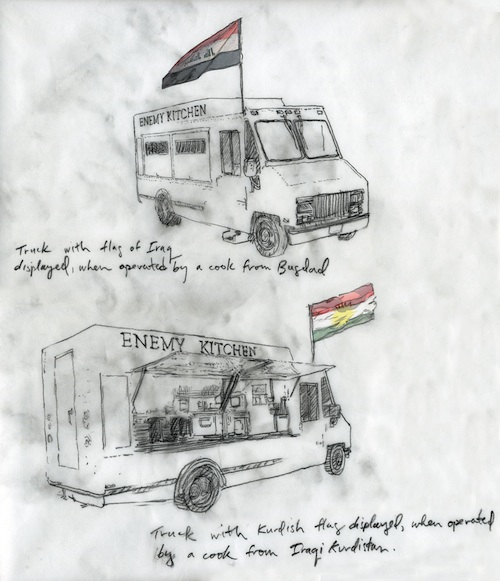

Michael Rakowitz, working sketch for "Enemy Kitchen (Food Truck)," a commission for "Feast," 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects.

So my initial idea was to open a restaurant, but I now live in Chicago and opening a restaurant here is different than it is in New York. There were no Iraqi restaurants in New York until 2007, when La Kabbr opened up in Hell’s Kitchen and then, unfortunately, I think it closed in 2010 or 2011. In Chicago it’s very different because the city has one of the largest expatriate communities in the world. I recognized a lot of items that were on menus of restaurants here that declared themselves Middle Eastern or Mediterranean. But kubba or masgouf or things like that were evidence or traces of their culinary history in Iraq. In the same way, the trigger for Return was my visit to Sahadi’s in Brooklyn where the date syrup was marked ‘Product of Lebanon’ but it was actually a product of Iraq. There’s this veiling of the provenance, of where those products come from, which was a way that Iraqi companies circumvented the U.N. sanctions. And so this food truck is, in a way, about a circumvention of identity, about a certain kind of fear, about what it means to be labeled specifically Iraqi and what that means in America.

I decided that, better than opening a full-on restaurant, would be to collaborate with this really rich community here in Chicago … These restaurants are located in very specific communities, so the idea was that the mobility of Enemy Kitchen would not only introduce that food to different parts of the city but also make people aware of this almost repressed topography … Mobility is also an opportunity for the truck to travel to places like the South Side, where there’s a huge amount of military academies and young kids who are from this area end up getting recruited. I liked the idea of the truck being this kind of dangerous ice cream truck parked outside of the military academies and presenting another kind of narrative to these kids who might be buying lunch from the truck. Also, the truck is for me a way of engaging with a kind of contested culture here in Chicago, where food trucks are under attack essentially … There’s something about that that’s kind of nice as a way of indirectly referencing territorial contest or a certain tension around where you are and are not allowed to be.

Michael Rakowitz, "Enemy Kitchen (Food Truck)" parked outside the Smart Museum on opening night of "Feast", 2012. Courtesy the Smart Museum of Art.

NC: So how many people are on your team?

MR: The restaurant I’m working with first is a place called Milo’s Pita Place. Right now I have Milad, who is their chief cook, his brother Mike, and his dad Jawher. They’ve run restaurants in Mosul, Iraq, a couple of restaurants here in Chicago and in Mexico as well. In terms of the Iraq vets, we have about four who are working with us now. I’m also working with the Iraq Mutual Aid Society and we’re employing cooks who are from different regions of Iraq. So a Kurdish family is going to have very different recipes than someone from Basra, for instance, so we’ll be able to represent those regional cuisines and Milad will provide oversight for the cooking of those recipes. Everyday a different flag will be hung outside the truck – a Kurdish flag when it’s a Kurdish chef or an Assyrian flag when it’s an Assyrian chef. It will kind of speak to geographies in Iraq that people don’t really know about except when they talk about sectarian violence. In this case, it’s more about sectarian cooking.

NC: You’ve worked with food on a few occasions, developing two projects for Creative Time and now the food truck for Feast. What is it about food that you’re drawn to?

MR: When I was a student, one of the professors who changed my life is this really amazing artist and architect named Allan Wexler. He works with the social environment that gets created around the gathering for a meal. Growing up in a Jewish household, I was attracted to the way that Allan would enlist those rituals. Allan was great at pointing out the way that ritual, in terms of the scripts and the very rigid rules of something like doing a Passover Seder, were not so different from Sol Lewitt’s sentences on Conceptual Art. I loved that intersection quite a lot. You know, this was a rich part of my life but I was feeling like those traditions wouldn’t find a way into my practice, that they were mutually exclusive. And so I was interested in the ways that Allan played with ritual and the implements that accompany ritual from a design and art perspective—the design of silverware, the design of tables, the design of architecture. He introduced Okukura’s Book of Tea in his class and that’s been such a huge influence on me.

You know, cooking is like building things and I really love that sculptural quality of doing something like making a kubba, which is this rice flower dumpling my mother taught me to make. There’s something about consumption and ending up with nothing afterward. You end up with an experience and the evidence of it is something that’s been totally emptied out or traces of something on a plate or tablecloth. It’s also the immediacy of a call and response. You put something out in the world and it’s not that people might see it or might engage with it. In the case of cooking, people are right there engaging with it. I liked the way that food created a participatory moment that wasn’t threatened by the failure that so many participatory projects experience, which is where you put something out in the world and all you end up with is a dead project. I’ve made things like that and I think a lot of artists who work in this realm have made things like that. In the case of a meal, people are there and you’re making something with them and for them. I liked the way that food dealt with participation, form, and social engagement. It seemed to be the perfect tool.

NC: It seems this food in art thing has become, well, trendy. I’m curious to know if and how that has impacted your work over the past few years?

MR: There’s something that’s simultaneously reinforcing about the way this kind of practice has pervaded the field, but then I get skeptical anytime something becomes a fashion. I want to head for the hills when that happens. It maybe means that the frictions of it have disappeared, that it’s almost predictable. One of the reasons I started doing what people call social practice was because I was reacting to the dissatisfaction that I felt with my work just showing in a gallery. But I needed that to create an adequate amount of claustrophobia or friction to allow me to decide, ‘Well, f**k it. I’m going outside. I’m going to do something out in the world.’ So I worry a little bit about what happens when you start to say, okay, well this is a thing, so now it’s a category, and now we’re going to make a niche — a research nice, a study niche, a curatorial niche. My fear is that it deadens it, it takes the air out of it, it softens it. But that’s not to say there aren’t projects I find incredibly powerful. Feast is a case in point. I think it’s a really great, critical, looking back at what has become now a lineage of artists who are working with these similar tropes or tools. And there’s something really great about having conversations with different artists and having projects pop up here and there that you feel a kinship with. So there’s something both good and unsettling about it.

*This interview was conducted for an article in the forthcoming issue of Public Art Review.

Pingback: Centerfield | Fielding Practice Podcast #13: “Feast” (or Famine?) | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Gastro-Vision | The Best in Food-Art 2012 | Art21 Blog