After a fitful night on the redeye from Los Angeles, I took the train from the Philadelphia airport to downtown, then got on a bus to a coffee shop where I regrouped over a delicious breakfast. I dragged my suitcase to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where I was immediately irritated about being asked to open it for inspection when I walked in the door. I’m not sure what that was about, since there was no actual “searching.” I have a difficult time understanding our culture of security, it seemed to me that the idea was less about seeing what was inside my bag and more about having the museum visitor understand the idea of authority. Perhaps it was performance art. In any case, I grumpily opened my backpack and suitcase, then took it straight to the coatroom where it was safely stowed away.

I beelined to the room at the end of the European section where the works of Marcel Duchamp are squirreled away. I got there in time to watch a school group arguing whether or not his piece “Bicycle Wheel” was art or not. It seemed to be a high school group, accompanied by a a museum educator who had asked for volunteer students to stand up and present their two opposing viewpoints to the class. While I waited for what I was hoping would be a heated argument to erupt, I wandered into the darkened room that houses Étant donnés. A dude was in there looking lost and asked me, “is there anything in here?” I pointed to the door and he wandered over to look through the small peepholes. “I don’t see the waterfall,” he said.

Marcel Duchamp. "Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage . . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . . . )," 1946-66. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of the Cassandra Foundation, 19691969-41-1.

Back at Bicycle Wheel, a young man stood up to say that it wasn’t art because it was a bicycle wheel and that it wasn’t beautiful and that other things in the museum were obviously art, but this is not art. The rebuttal was made by a slim girl with a stripey shirt on who gave a compelling argument about how it was art because beauty is different for everyone and maybe “Marcel” had gone on a bicycle trip or had written a poem about a bicycle. The museum educator then asked everyone if they would think about this piece when seeing bicycles in the future and some said “maybe” and others said “no way.” Meanwhile, during their dialogue, the dude had brought his dude friend over to peep in the peepholes in the small, dimly lit room. They were giggling and wearing big dayglo stickers which I think identified them as parents to a group of very young children who were making art with fabric strips in another room while the parents were all taking pictures of them with their cellphones. The Philadelphia Museum of Art is a very lively place on a Thursday morning, crowded with visitors.

After the arguments about art were completed, the students picked up their stools and were whisked to their next location. “We’re not going to that room,” said the museum educator, pointing towards the darkened room with the peepholes. I’d seen Étant donnés for the first time a few years ago and was perplexed and blown away. I’d heard the story of its making, that Duchamp had told everyone he was playing chess while secretly working on the piece for 20 years. I’d seen images of it for years, but nothing quite prepared me for seeing the piece in real life. Growing up in a world of images, copies, simulacra, and their accompanying theoretical texts made me a cynical viewer. In many cases the cynicism is well-founded. There is a lot of art whose book reproductions are equal to schlepping to see it in the flesh. But this piece is different. I wasn’t sure if it was the hype, the anticipation, or the actuality of the experience, the thing itself, but the experience of putting my eyes to the well-worn wooden door, the smell of the voyeurs who had done the same for decades before, the view of the headless naked body holding a gas lamp… it gave me goosebumps.

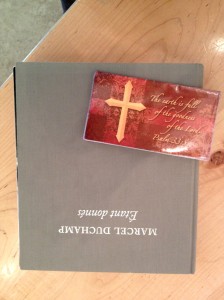

I sat down on a bench in front of the The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). From there you can look through the piece and out a window to the early spring. Next to me on the bench, someone had left a datebook that had a bible quote on the cover sitting atop a catalogue for the show about Étant donnés that had been put on by the museum a few years back. I couldn’t help but wonder whether the presence of the bible quote was somehow related to the material on which it was perched. Was someone using this artwork as an opportunity to proselytize? I don’t recall hearing that Duchamp was a christian, but maybe he was possessed by the devil and this was a gesture of exorcism? Meanwhile, the dude had brought his dude friend back to the peepholes and I was saddened that the high school students weren’t allowed to see it. I knew artists whose lives had been changed by that piece.

Fueled by jetlag and coffee, I hunted down the museum educator and confronted her about her vigorous refusal to allow the students to see what was widely considered to be Marcel Duchamp’s most important work. During her spiel to the students, she had bragged that people came from around the world to see Duchamp’s work at the PMA and that many important musicians, including David Bowie, had come specifically to see it. But without showing the students one of the works that the luminaries were actually coming to see seemed unfair. Sure, they were probably happy to see The Large Glass and the other works in that room, but the real draw, the crazy insane thing that no other museum could dream of owning, is a small darkened room with two peepholes and what lies beyond.

The museum educator explained that museum policy does not forbid tour groups from seeing the piece, but that she does not feel comfortable bringing students to see it unless it is specifically requested by their chaperone. She herself had had a bad experience when she was a student. Shown images that she found to be pornographic, she was disturbed. Shielding students from potentially disturbing work seemed to be important to her. I could imagine that having a group of twenty students lining up to look in the peepholes could also be time-consuming, but the way the students were whisked away and told not to look was upsetting to me. Hopefully, the most interesting kids of the bunch would do what they should do… when told not to look at something, they will make a mental note to come back. As soon as they have five minutes to go to the bathroom or graze the museum unaccompanied, they should get their asses back to that room and drink in one of the twentieth centuries oddest pieces of art.

It’s always tough to decide where the line is in terms of what to show and what not to show. Some students do have fragile constitutions, while others are so jaded nothing will affect them at all. At what age is it appropriate to expose students to “difficult” work? When are students ready to see nudity in art? Étant donnés seems tame by today’s standards, but it obviously still packs a punch.