In The Cartographer’s Conundrum, a large installation currently on view at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (Mass MoCA), artist Sanford Biggers maps artistic, cultural and spiritual practices, other disciplines and fields such as Afrofuturism, music, and sacred geometry. The average visitor probably knows very little about these concepts, their diversity and the relationships that exist between them. However, Sanford’s presentation draws you in and provokes an unrestricted sort of curiosity that might lead to a more global understanding of the various issues involved. The Afrofuturist perspective was influenced by pioneers Sun Ra, George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic, Afrika Bambaataa, and others who produced works that resonate with contemporary artists and performers like Cauleen Smith, Rashid Johnson, even singers Erykah Badu and Janelle Monae –these examples are good starting points for exploring the themes in Sanford’s show.

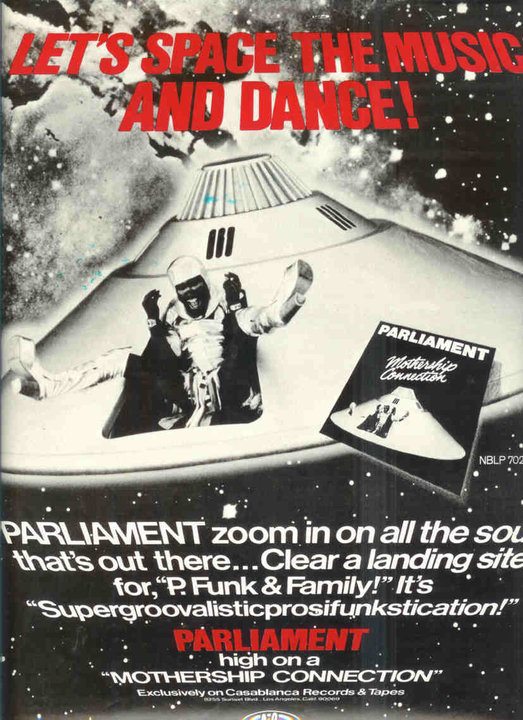

“I figured another place you wouldn’t think black people would be was in outer space. I was a big fan of Star Trek, so we did a thing with a pimp sitting in a spaceship shaped like a Cadillac, and we did all these James Brown-type grooves, but with street talk and ghetto slang.” (George Clinton)

George Clinton and Parliament. Mothership Connection poster circa 1975. Courtesy Casablanca Records.

Curator Denise Markonish describes Sanford Biggers as a “child of hip-hop, breakdancing and graffiti culture.” As Sanford and I were born in the same year (1970) certain aspects of this work resonate on a personal level and others emerge as part of the “spirit of the times,” in which artists, scholars, and mathematicians, for example, intermingle different perspectives and creative ideas to produce new spaces for production and discourse – see Cai Guo-Qiang‘s and Hiroshi Sugimoto‘s contributions in Mathematics: A Beautiful Elsewhere. Here, Sanford’s work is part of what he refers to as the “hip-hop ethos,” as well as Afrofuturism as (in this case) a platform for contemporary artistic production and discourse.

“Afrofuturism plays tricks with history, wrapping street culture with science fiction to advance new and alternative views of the world.” (Denise Markonish)

Creative syncretism, or as Sanford describes, the “study of ethnological objects, popular icons, and the Dadaist tradition,” intersects with Afrofuturism, a parallel cultural practice that brings together disparate technologies, new rituals of communication, and communities that remain open to the incorporation of older knowledge contexts. Scholar Roy Ascott argues that syncretism – the attempt to reconcile disparate practices – contributes to “our understanding of multi-layered worldviews” that are emerging with our social-cultural and spiritual engagements. These engagements reach across divides. Ethnomathematics is the study of the use of culture with the presentation of math. Ethnomathematician Ron Eglash wrote A Geometrical Bridge Across the Middle Passage: Mathematics in the Art of John Biggers (2004) to create awareness of the process through which this knowledge progresses and is exchanged. After Sanford talked about his contemporary mandala at Emory University I introduced him to Ron (my dissertation advisor) via email. Inspired by the response, I made the trek to Mass MoCA from Georgia Tech.

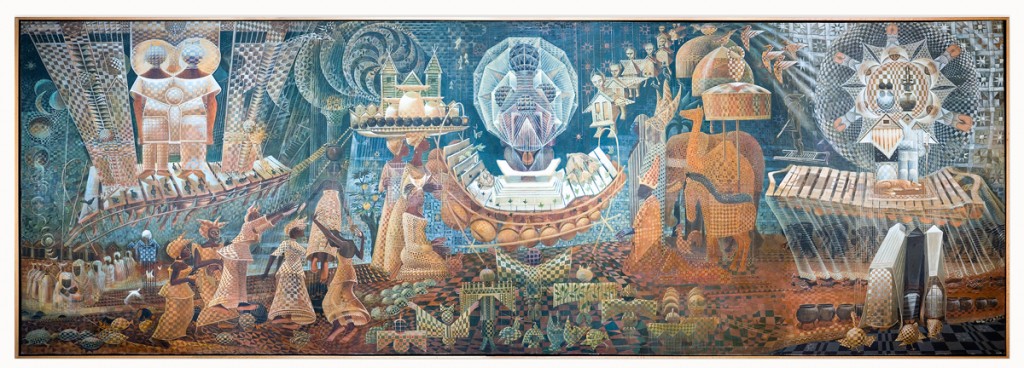

The Quilting Party, an early 1980s mural by the late artist John Biggers (possibly related to Sanford), informs The Cartographer’s Conundrum and demonstrates the elder Biggers’ personal aesthetic and complex symbology that imparts layered meanings both as immediately recognizable symbols of daily life in the American south and spiritual connections to African heritage. Ron’s essay offers a different approach to the analysis of artwork as a cultural artifact, i.e. based on John Biggers’ use of sacred geometry. Mathematics often appears in art with pyramids, music, five regular polyhedra (Platonic solids), and fractals. Culturally situated design is also present in Sanford’s work as he extracts certain aspects, translates and remixes them to address problems and construct new spaces or worlds.

Sanford Biggers. “The Cartographer’s Conundrum;” centerpiece (2012). Courtesy the artist and Mass MoCA.

As a practice, worldmaking implicates (visual and aural) language as a way to reflect and shape realities. The sense that order is imposed on a piece of a world by a sound, symbol or image is only one example among innumerable possible ideas: The artist adds something, deletes something, substitutes one symbol/image/sound for another, re-arranges elements; and with each change, the “reality” offered to the viewer changes. Understanding this process is critical to deciphering the complex symbologies presented in John Biggers’ worldview and Sanford’s translation.

“… Sanford takes essential geometries from John’s canvas, projecting them into the reality of three-dimensional space.” (Denise Markonish)

A tiled floor pattern based on “interlocking six-sided cubes” repeats quilt-like patterns in John Biggers’ mural, simulates the electronic play space in the classic video game Q*Bert, and is very similar to another piece by Barry McGee currently on view at the Prism Gallery in Los Angeles. In mathematics these patterns (tilings) are attractive because of their visual beauty, depth, and historical aspect.

In the cavernous Mass MoCA space the flat floor patterns are punctuated by smaller assemblages of objects such as instruments and mirrored stars, that lead visitors to an amazing centerpiece (see images above). Speakers placed around the space create fields of sound.

“The (main) room ends in a pulpit of sorts, here taking the form of a vortex of musical instruments, a piano hanging in midair surrounded by pipes from a church organ, spraying out like in Bernini’s Ecstacy of Saint Theresa (1647-52).” (Denise Markonish)

Rows of repurposed church pews take flight and become colored, plexiglas objects that are made of the same material that is placed over some of the window panes, casting multi-colored lights across the room. On the upper mezzanine level The Quilting Party mural is, as noted by Markonish, “the preacher and we his/her congregation.” It can be seen directly above the pulpit. On display behind the mural is a repurposed quilt by Sanford, possibly a nod to the concurrent exhibition, Codex, now on view at the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida (which I covered for Art21) and the artist’s involvement in music. In the center of the quilt Biggers uses a drawing based on a harmonograph which is a music visualization tool that that uses pendulums to draw a geometric image. Like similar works by urban artists such as Doze Green and MARS1 and Moneyless and Mark Lyken, this particular quilt piece by Sanford marries geometrical designs with detailed line work to create what could be a portal to another dimension.

In an adjacent room two large screens display Sanford’s video, Shake, the second part of a trilogy about the formation and dissolution of identity. This piece features Brazilian-born, Germany-based artist, stuntman, clown and DJ Ricardo Camillo. Sanford travels with Camillo to favelas in Sao Paulo and the ocean. In the final scene, Camillo is transformed into a silver-colored avatar.

This avatar (wearing platform boots George Clinton might wear) is an incarnation or manifestation that directly connects Camillo (in the video) to his and Sanford’s Afrofuturist predecessors; and Sanford’s constructions to Ron Eglash’s and John Biggers’ merging of everyday life practices with cultural heritage and spirituality. Roy Ascott notes the “emergence of spiritual and psychic syncretism in Brazil in the Afro-Brazilian movement of Umbanda,” an Afro-Brazilian religion that blends African religions with Catholicism (among others) and indigenous lore. Ascott argues that all religions are syncretic in their absorption of external elements either “consequent upon colonization, conversion or simple geographical proximity.” The key to solving the “conundrum” that Sanford presents to us lies in these connective threads that transcend physical geographies and challenge conventional modes of thought and practice. Sanford’s work inspires the re-appropriation of existing cultural artifacts, transforming them into portals to alternative futures. I’m interested in exploring how this work can be translated into serious games for cultural heritage and other projects as a way to engage people who are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics (STEAM). The worldviews presented in The Cartographer’s Conundrum support this endeavor, are open to change and adaptation, and exerted by technological innovation.

The Cartographer’s Conundrum closes October 30, 2012.

Also check out The Triptych: Sanford Biggers, part of a documentary that was recently screened at Brooklyn Museum.

Pingback: Sanford Biggers at the Mass MoCA

Pingback: Yayoi Kusama at the Whitney: Accumulation, Infinity and the Multiverse | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Art21 2009 to the Present « SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Deep Sea Dwellers: Drexciya & The Afriscape | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: No One Way To Learn Something | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Afrofuturistic Freedom Dreams | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Shuffle, Shake & Shatter Residency with Sanford Biggers | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: The Girl Who Dared to Dream: My Ph.D. Journey | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Techno-Vernacular Creativity: Hackerspaces & Afrofuturism | Renegade Futurism

Pingback: Critical Play: Radical Game Design & STEM | Renegade Futurism

Pingback: Putting In Work: A Long-Term Dream Is Being Realized | Renegade Futurism