This account is somewhat of an autobiographical approach to three Mexican artists under forty. The connecting thread beyond their age and nationality is that I have seen their work in person, and their own trajectories are as nomadic as my own. Though none of them has a “Mexican aesthetic,” their latest projects engage with capitalism and contemporary life in various ways.

I first became acquainted with Humberto Duque’s practice in 2008 at a group exhibit, Cutting Fine, Cutting Deep, held at the University of the South featuring works by Swiss and North American artists. I was intrigued by the fact that a guy from Mexico City was speaking about his work in the middle of rural Tennessee, which only brought home the absurdity of my own time teaching there. This was over four years ago, and there are several things I remember about his talk: awkward videos, references to pop culture, a descent into a cartoonish universe, and his love of baseball. His latest projects were completed in Japan, at the CCA Kitakyushu Research Program 2011/2012.

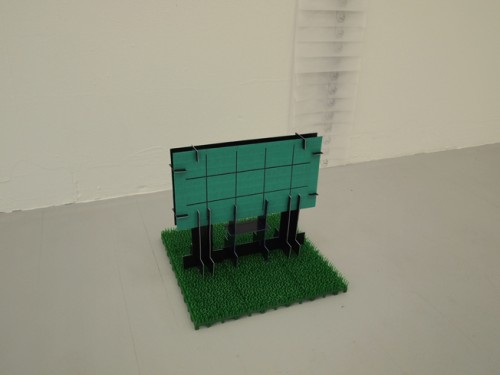

Duque’s works are oblique and seemingly cheerful, and their strength comes when several of them are exhibited as a group in order to propose a narrative scenario that is never quite clarified. Works from the series Conspiracy to Commit Public Nudity tread the line between dreams and daily life. They don’t form a unified story, but rather, link elements such as science fiction, architecture, language, and baseball. This series relies heavily on pieces that evoke discrete architectural structures, creating what appears to be a community or neighborhood. There is a house, a fragment of a stadium and scoreboard, a diving platform and an upside-down billboard. This is Americana, and the installation of the works underlines their interrelated nature.

Humberto Duque, from "Conspiracy to Commit Public Nudity," 2011. Pencil on plasterboard, plastic, tape.

Conspiracy’s simple structures are made up of plastic sheets, clothespins and artificial grass. In many ways, they allude to the homogenous nature of American suburbs, while the many references to baseball reinforce the importance of regularity, rules, numbers and statistics. Duque even points to fame, since one of the pieces consists of an upside down image of a female baseball player. Might this not be a billboard connecting American domesticity, the suburbs, baseball, the pursuit of happiness and celebrity, all of which are further articulated through the orderly arrangement of these architectural pieces? Isn’t this system congruent with the pecking order of high school and its athletics as a metaphor for existence? Is it not the kind of social structure one finds in small towns scattered all over the United States, which is often replicated even in large cities? Despite the complex language articulated by the pieces as a group, there remains something simple, handmade and humorous about each of them, which belies the regularity of their shapes and materials.

Duque’s second series, Malady of the Discontent (which was also created in Japan) is willfully disjointed in comparison. While Conspiracy referred to a blueprint for the American dream based on domesticity and athleticism through geometry, Malady depends on several readymade objects that coalesce in strange ways, rendering them useless, as if they were lost or their function had been forgotten. Two oven mitts are suspended by sticks of wood in There Was No Tomorrow, Not Today, for example. Baseball players that appear to belong to the same team compete in field of clouds in the Longest Hour, and small plastic fans posing as outfielders achieve a fragile equilibrium by blowing air, allowing a silver-colored cellophane sheet to float. Here, baseball has been transformed from a game of efficiency and numbers to a seemingly senseless pursuit based on chance. Rather than provide certainties, Malady poses hubris as an alternative, eschewing rigid geometries in favor of a looser configuration of works based on organic shapes and mismatched objects. No clear formal thread binds these works, as they constitute a series of impossible and contradictory stances, which clash with the narrative (system?) proposed by Conspiracy. In many ways, if Conspiracy looks back at the sterile mid-century suburbs and progress–two important modernist myths–Malady responds to this by refusing to subscribe to a single narrative.

Duque is currently working on a project for the Denver International Airport as well as on a piece that will be installed in a park in Norway.

Shifting to Javier Pulido’s practice constitutes an aesthetic jump, though both artists are steeped in mass culture. Pulido might also be the funniest of those discussed here, both in person and in terms of what he does. Moreover, there is something grandiose about him, and it’s channeled as an acerbic social critique that places him (or rather one of his alter egos) at the center of his art.

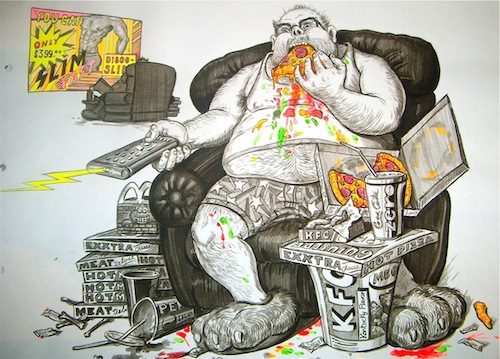

I reviewed Eat DIVINESS, Pulido’s solo exhibit in Guadalajara last year, noting that his preparatory drawings for a campy musical are in essence a reminder that we are all messed-up individuals faking our way by alternately consuming as much as we can and repressing our desires. In these works, the idea of the pig as a stand-in for consumer culture, and for the consumer herself, is what binds them together. They are a grotesque mirror he holds up to himself and which one can hardly turn away from. In essence, they approach capitalism by noting the latter’s hold on our fragile egos.

Having myself grown up in and then left Guadalajara, which is one of the most conservative cities in Mexico, Pulido’s harsh self-representations as a flawed and desperate individual made a deep impression on me (the self-portraits allude to a character from the movie project, but the sitter is him, no doubt). Given that this city is known for its religiosity, his embrace of self-debasement and the double lives people must lead in order to blend in is fitting.

Pulido is currently working on filming a movie based on this vision, which is perhaps what drew me to his works: the idea that they are meant to coalesce into something larger, a grand statement. They create a fascinating world, a critique of capitalism that is ridiculous, gauche and poignant at the same time. A second iteration of this project, You Are What You Eat, was presented at Ex-Teresa in Mexico City. The greatest departure was that the artist involved the attendees in a strange ritual that was half labyrinth, half trip to the slaughterhouse (see video above). This journey placed the viewer within the mind of a deranged murderer, but also mimicked the way in which the constant bombardment of advertisements prompts us to consume. One could describe both states as full of frenzy. Once inside this strange corral, it appears that the capitalist seduction becomes an endless nightmare in which the choices that are supposed to make us unique transform everyone into trapped pigs!

Pulido lives in Mexico City, but his aesthetic mocks global capitalism. He comes from a family of butchers.

Joaquín Segura’s current practice is more focused and subtle than that of Pulido. Segura’s works are mostly sculptural and object-based, and it is possible that one of his most interesting projects was never exhibited as intended. Untitled (Gringo Loco) is a large-scale sculpture which imitates Las Vegas’ famous welcome sign and mocks American cultural colonialism with the words: Fuckoff you Chili-Eatin’ Gringo Loco Up Your Ass.

The sculpture was supposed to have been placed at the site of the Guggenheim in Guadalajara, a project that had been abandoned by 2009, when this occurred. Given that at the time, Los Angeles was the guest of honor at Guadalajara’s book fair, one of the most important cultural events in the city, the authorities decided to revoke Segura’s authorization to install the sculpture in such a site. Here, Segura’s critique against the Guggenheim and his mockery of Guadalajara’s own dream to become a cultural franchise was rendered even more potent by the inability to show his piece. Furthermore, it reminds us that the “gringo loco” goes as far as the Mexican lets him and that repression is often worse when directed at our own compatriots, since Segura was escorted from the site at gunpoint. Though it makes for an interesting story, this is precisely the kind of occurrence that explains the challenges contemporary artists face in Guadalajara.

Segura’s latest solo show at Yautepec in Mexico City dwells upon the relevance of political activism and terrorism, a subject that’s somewhat of a departure from his previous attacks against institutions and power. The exhibit, titled A Brief History of Breakdown, acknowledges the impossibility of dissent by taking objects linked to this posture and rendering them useless. The first series consists of still life drawings of homemade bombs, detailed representations that manage to make these weapons appear quaint.

Joaquín Segura. "Exigimos justicia para ... "(from the series, Exercises in Selective Mutism), 2012. Protest banner, white paint.

The other series consists of signs from protests that Segura silenced by whitewashing them and hanging them from the wall, rendering their messages illegible. They belong to the series Exercises in Selective Mutism, and their individual titles remind us of each cause they advocated for, together presenting a litany of unheeded demands.

One of Segura’s signs has been turned into a fragile teepee, an allusion to homeless camps, to the myriad protesters living and sleeping outside Mexican public institutions, and even more poignantly, to the dying traces of indigenous cultures. Might they also be an allusion to the all-too common narcomantas (or narcoblankets, a term referring to banners bearing threatening messages) meant to glorify a specific kingpin’s power and violent deeds?

The muted signs are perhaps the most arresting elements exhibited, and their formal beauty recalls the process by which subversive cultural elements are quickly absorbed by the culture industry. Their stillness and plasticity reminds me of the draperies worn by Zurbarán’s and other Baroque masters’ unflappable saints, while the monochromatic character of the entire exhibit functions like white noise, representing an inability to communicate. The entire installation happens to be yet another way to note the buzzing sound of pointless protests, the stillness of the status quo. Overall, Segura’s sharp cynicism remains, but has shifted from anger towards a sad rumination on the frail indexes of protest. That these works are exhibited at a commercial gallery is no accident–it is only the natural result of art’s place within the cycle of co-option.

Segura participated in the latest edition of the Bienal de Pintura Rufino Tamayo (2011). He will exhibit his works at Enjoy Public Art Gallery in Wellington, New Zealand in 2013 as part of a two-person show with Tony Garifalakis.

***

These three artists criticize capitalism and power in different ways, ranging from a droll articulation of the structures that make up the American suburb, to campy drawings that force us to confront our own sick desires to consume, to muted, helpless accessories of protest. While Duque seems to evoke a highly structured and oppressive society, Pulido and Segura point towards our inability to escape or combat it, noting how we all fall through its loopholes, often willingly.