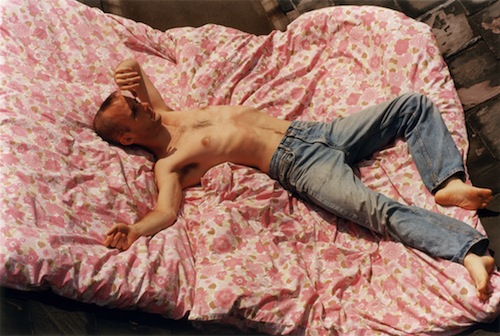

Wolfgang Tillmans. “Moby Lying,” 1993. Inkjet print. Courtesy the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

When the film Kids, about NYC’s skateboard culture, came out the summer of 1995, I was 20. I found it incredibly hard to watch—too familiar and yet an alien viewing experience. No one had seen anything like what Larry Clark was doing with our generation on screen—the drugs, and unprotected sex, that New York preternatural streetwise hustle mixed with alarming stupidness—it was intense and disturbing. Seventeen years went by. Then, last week, I re-watched it. It’s a remarkable film—how it reflected a range of generational reactions and experiences, how accurately it took the temperature of the moment. It made me hungry to see the ’90s again: the expressions we used, the parties at N.A.S.A., the fleets of skateboarders, the sound of them scraping decks and grinding cement curbs. The film is how I remember the city itself to look, saturated in primary colors. To know that this New York once existed, to have lived through it, feels powerfully sad and strange. Even with the appropriate twenty-year distance, that time is still amorphous, emotionally complicated, hard to pin down. Still overwhelming in a sensory way—the indie music, and the skate t-shirts, those short haircuts we had.

What seemed like the entirety of early ’90s culture to me was perhaps just one small, influential subset. The New Museum’s five-floor retrospective of one year in New York, NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, opened last Wednesday, and it’s just as richly compelling, cohesive, and yet evasive an experience.

The fourth floor is arranged to deliver a sensory hit, or perhaps provoke the memory of one. Rudolf Stingel’s lush orange carpet, in a particularly reminiscent shade, is set off by a string of light bulbs suspended from the ceiling, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Couple) (1993). The two artists would begin collaborating that year. Into the darkened room, Kristin Oppenheim wistfully intones Sail on Sailor in the haunting vocal lineage of Portishead and Mazzy Star. Related, high up on the wall in the alcove, is a piece by Robert Gober, whose work never fails to be enchantingly strange—Prison Window (1992) is a small barred window, behind which sits a beguiling, beautiful little piece of sky.

Cheryl Donegan. “Head,” 1993. Video, color, sound, 2:49 min. Courtesy the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix, New York.

It’s a nice reprieve. One floor down is overwhelmingly, intensely devoted to sex in the ’90s, in its varied and troubling manifestations, and its consequences. The centerpiece is Paul McCarthy’s Cultural Gothic (1992), a large, mechanized, ghoulish subversion of father-son bonding, involving sex with a goat. The periodic thrusting and loud stamping of goat hooves on weathered boards steals the majority of the room’s attention. The mesmerizing and viscerally disturbing Cheryl Donegan video Head (1993), a supposedly comic riff on MTV culture, is a single take of the artist licking and spitting milk spurting from a green container while Sugar’s “A Good Idea” rages in the background. Her fixed concentration on the job carries the piece. Lutz Bacher’s My Penis (1992) is the most steadily demanding presence here, though. A small TV sits on a folding chair, looping a seconds-long clip of William Kennedy Smith’s 1991 rape trial, in which he loudly testifies “I did have my penis” and then winces. Again and again. He was later acquitted after the testimony of three women who also claimed to have been assaulted was deemed inadmissible. His Kennedy good looks. His perfect hair.

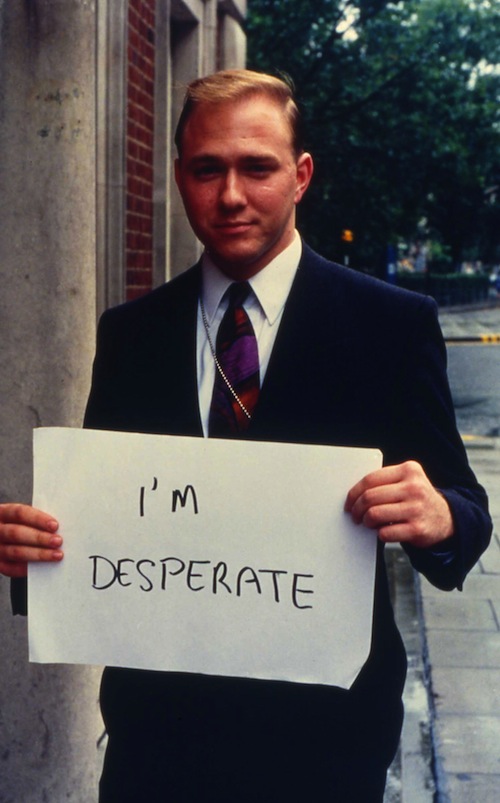

Gillian Wearing. “I’m Desperate,” from “Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say,” 1992–93. Chromogenic print mounted on aluminum. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

In 1993, the AIDS crisis was entering its second decade. In the United States alone, more than two hundred thousand people had already died. In the autobiographical, archival, documentary film Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993), Gregg Bordowitz captures the incomprehensibility of epidemic and disease, cutting back and forth between societal and excruciatingly personal vantage points. HIV-positive and a vocal member of ACT UP, Bordowitz conveys the raw despair and the loneliness of living with the diagnosis, missing not so much sex, but intimacy. “I don’t trust people who want to be in a relationship with me…with a sick person.”

For as much as the AIDS crisis was about fear, it was mainly about loss. One of the most beautiful and affecting works in the show is Nan Goldin’s series of four portraits of her Parisian art dealer, Gilles Dusein, and his partner, Gotscho, an artist. In these large saturated Cibachrome prints that are immediately recognizable as hers, we watch Dusein’s heartbreaking deterioration from a handsome, healthy looking young man to an emaciated elderly person within the space of a year. The gentle, affectionate gestures between the couple, as well as their alarming physical differentness at the end, say everything about the enormous cruelty of this disease.

Political and social history are evident in places: Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”; photographs of a decimated Sarajevo from a trip Annie Leibovitz took with Susan Sontag during the height of the Bosnia-Herzegovina civil war; Pat Robertson/Christian Coalition’s vituperative campaign against Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography, and Glenn Ligon’s response. But it wasn’t until I came upon Peter Cain’s Pathfinder (1992–93), which feels enormously out of place—photorealism so out of step with 1993 as to look progressive—that I realized there was a cohesiveness to this exhibition that wasn’t entirely curatorial, something aesthetically indicative of a time period, a sensibility, an undercurrent of social preoccupations that could go a long way to explaining 1993 back to its ex-inhabitants. Or a version of it, anyway. It’s an exciting time when a decade is first getting discussed and explored in all its multitudinous, complicated, and personal dimensions. Before it’s boxed up into a collection of traits—’80s synthesizers, Reaganomics, Neo-Pop. It feels, somehow, alive again.

On the first floor is a collection of Kids ephemera, skate decks, production stills, photographs of the city, even the door to Larry Clark’s studio, from when he was researching the film. It looks like a tidier version of my brother’s back then, plastered with Think, Fuct, Plan B, other skate logos. I had jolts of memory here, looking over these mementos—they’re more true, but not even fractionally as real and evocative as the film itself, and what it calls up. In trying to understand the past, art is an extremely fine vehicle in which to get around. Maybe it’s art’s overwhelming preoccupation with its own cultural present. Or maybe it’s because art is what we use to transcend the often unremarkable, day in-day out experience of living through it.

NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star is at the New Museum in New York through May 26, 2013.

Pingback: Inspiration | Make everyday Outstanding