In the following back and forth with artist and writer Jen Schwarting, we discuss her ideas and process around her current Drunk Girls series. Born in the Bronx, Schwarting now lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She makes sculpture and collage, writes about art, and teaches at Pace University in lower Manhattan. Her work explores the boundaries of class, sex, and gender while mining territories of feminism, pop culture, social media, and histories of representation.

Amanda Beroza Friedman: In your current series, the focal point of each construction is a printout of a jpg pulled from a Google search of the phrase “drunk girls.” How did you come to this search?

Jen Schwarting: Like a lot of people, over the past several years I’ve become increasingly concerned about issues of privacy and the ways in which the Internet and social media have altered or removed certain levels of privacy we used to enjoy. And because I teach at a university, I find myself talking with other faculty about how grateful we are that Facebook and especially camera phones didn’t exist when we were in college. In my teens and twenties, I felt a real sense of freedom to experiment without exposure, and I think that was crucial to my development as an artist. It seems different today, where constant recording and overexposure defines so much of our culture. I’m fascinated with this state of exposure and how it’s manifest in entertainment and social media, I also keep up with some very low-brow popular culture. I’m currently watching that new MTV reality show, Buckwild, featuring the manic, drunken behavior of twenty-somethings in West Virginia. So thinking about a kind of base entertainment, exploitation, and the dichotomies of privacy and exposure is what first led me to notice, and then start searching for, the many images of young, drunk college-aged girls publicly posted online.

ABF: How do you pick which image to use? I identify the art historical reclining nude pose.

JS: Having combed through the hundreds of images that pop up under the query “drunk girls,” I can say that many of the casual snapshots people post are pretty explicit, and I am wary of choosing images that are overly sensational. I gravitate toward pictures that are darkly humorous or nuanced in some way that might cause a viewer to do a double-take. One of my favorite photos depicts two women passed out on the floor of a college dorm room, lying in the same crumpled-over pose and wearing almost identical outfits, so that it is unclear at first whether it is one person reflected in a mirror or two people in the same sorry state. I also tend to choose images of women that are beyond drunk to the point of passed out, to emphasize a state that is oblivious and the opposite of conscious. On some level too, as you mention, I am considering the history of representation of the female figure, including Western art’s classical nude, so often lying prostrate, and the way those works of art throughout history ignited controversy over the limits of taste and taboo.

ABF: One of the earliest questions in feminism was who has control of a woman’s body, leading to the question of who has control of her image? In the current fluid state of images is this issue of image-control relevant?

JS: I think it is relevant. For most of the twentieth century, advertising, fashion, TV and film were directed and run by men—I’m suddenly picturing the ad agency on Mad Men—and women we can fairly say didn’t control their own image. During the feminist movement of the 1970s, many women artists began making work that challenged sexism and prescribed notions of femininity, as well as the image’s authority. For me, growing up in the 1990s, this question of who controls our image was something that I continued to talk about with friends all of the time—I associated it with feminism, but it also stemmed from a broader, national conversation about identity, race, and gender, and also indie culture and mainstream resistance. I was thinking about the genres of Grunge and Riot Grrrl music recently, and how a critique of image and control was built-in to so much of the film, art, and music we were into at the time. Today, in one sense, individuals have much more control over their own image and the tools of distribution. But as demonstrated by the “drunk girls,” we have also have less. As the parameters continue to change in the digital age a critical discourse on issues of control is not only relevant but more pressing than ever.

ABF: I inevitably want to interchange the word “still” for “image” when describing the “drunk” pictures.

JS: I do choose photographs that appear to be one moment captured from a larger narrative. Something has clearly happened prior to the moment the picture was taken, and because most of the women are unconscious—but the photographer is necessarily present—there is something foreboding, like the potential for a dangerous aftermath. The thought or threat of rape, or some equally horrifying outcome, is apparent in some of the pictures. I like the word “still” because of its connection to narrative, and to Cindy Sherman, who is a big influence. I think a difference is that Sherman’s [Untitled] Film Stills and early centerfold images implied a constructed narrative, pointing to representations of women in film and advertising. I am going for something similar in terms of stereotypes, appropriation, and representation, but it is complicated by the fact that the photographs I’m using allegedly depict real girls, and further, that their images are being used without permission.

ABF: How do you see your role connecting to the implicit voyeurism of Internet searching? Can you speak to the the anonymous authors and casual quality as found documents these photographs have?

JS: Now that practically any image is available to anyone with the Internet, and everyone we know is constantly looking at the activity of other people online, we are all voyeurs and it seems harder to define voyeurism in negative terms. What attracts me to and troubles me about these pictures of drunk girls is less the proximity to perversion and more, as you say, the anonymity of its authors. I imagine most of the photos are taken by friends of the drunk women and posted without their permission with the intention to humiliate. The spectacle of this—the cheap laugh and the mean-spiritedness of it—is a major component of the project.

ABF: You have mentioned in our conversations that it is not enough to simply reproduce the found pictures. Are your elaborate frames an homage to the nameless girls that they are built around?

JS: Once I choose a photograph to work with, I begin responding to specific aspects of the image, building out around them a larger photographic collage and textile frame. In a recent piece I honed in on one visual element—a blanket covering a girl on a couch—and painted the blanket’s repeating pattern around the picture for emphasis. I think I developed this process to spend extended time examining and considering each photograph, reconciling it in some sense. It’s interesting that you ask about an “homage” to the girls. When I started the project I had in mind a broad critique of the current state of entertainment, and drunk girls seemed like anonymous archetypes, generic casualties of over-indulgence and social cruelty. I thought the works would spark a dialogue about privacy, responsibility, and exploitation, but assumed an overt emotional response would be limited to me, my own politics and investment in the project. What has surprised me has been the way that the works seem to touch a nerve with viewers and have provoked really personal conversations, genuine empathy and concern about the individual girls and scenarios.

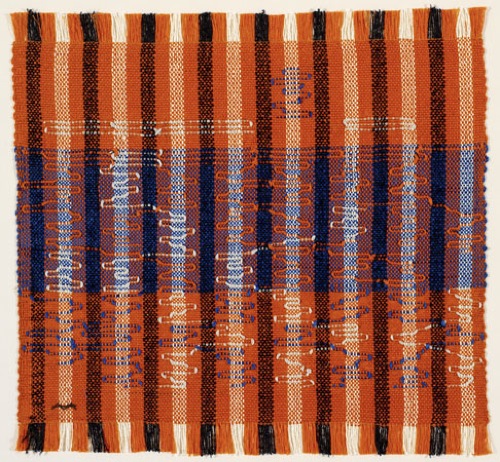

Anni Albers, “Intersecting,” 1962. Cotton and rayon. 15.687 x 16.5 in. Private Collection © 2008 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

ABF: There is a blatant juxtaposition of high and low culture in your referencing of what look like Bauhaus textiles and the modernist aesthetic alongside found representations of bad behavior (sharpie graffitied passed-out girls). Where do you see this discussion touching off from in these collages?

JS: I love the history of the Bauhaus; it embodied as a school and movement many of my major interests: teaching, education, labor, art, architecture, and high-minded idealism. But it was, in line with the times, profoundly unequal. Men could fully participate across all disciplines, and women could only do women’s work, like weaving. So I think about the incredible textiles that artists like Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl created, and their Modernist aesthetic surreptitiously exemplifying a struggle for equality, as much as intellectual design. And I’m using the aesthetic in my collages to bookend that history with the present— juxtaposing it with contemporary images of drunk girls and making these current scenes seem all the more gratuitous.

ABF: Will you address why collage was the medium of choice for much practice labeled “feminist” starting in the ’60s and why you find it a productive way to work today?

JS: What’s funny is that whenever I introduce a collage-based project in class, students invariably ask if they can bypass paper and glue and create the project in Photoshop, so it may become increasing difficult to argue for collage’s relevance. But in the 1960s feminist artists intent on social change, like Martha Rosler, used the very material they were critiquing to make their work—cutting sexual and domestic scenes out of lifestyle magazines to point to and subvert their meaning. The collage aesthetic is also deeply rooted in previous artistic movements of resistance and revolution, like Constructivism and Dada, so the technique continues to reinforce a political agenda. I still find the manipulation of images to be an important and powerful subject, and I like working within the history of collage’s social message. I also just really enjoy the physical act of making collage and engaging with the material of everyday life.

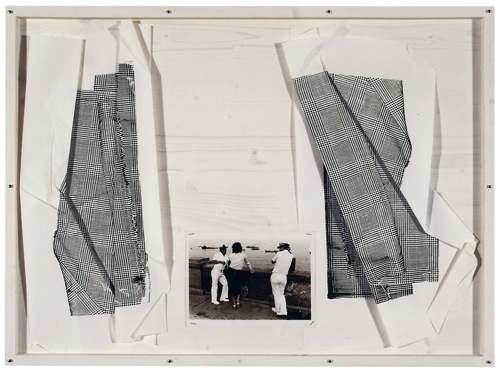

Rosemarie Trockel, “White Origami,” 2008. Mixed Media, 26 3/4 x 36 1/4 x 2 in. Photo: Photostudio Schaub (Bernhard Schaub/Ralf Höffner). Copyright: Rosemarie Trockel, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2013 (resp. ARS 2013). Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London, Gladstone Gallery New York and Brussels.

ABF: What artists are you looking at now?

JS: I just saw the Rosemarie Trockel retrospective at the New Museum which I thought was both excellent and also a bit uneven. Actually, I enjoyed the moments where it failed because it made her ongoing search for subject, materials and meaning all the more evident. She uses a lot of found images and woven textiles in her work, which I definitely relate to, and have considered an inspiration for a long time. The forth floor of the Museum was dedicated to showing dozens of her “book drafts,” these casual, hand-drawn and collaged book covers that are tongue-in-cheek ideas for books. A lot of them are really funny cultural critiques, riffs on advertising and fashion magazines, or art nerd in-jokes. She had both a book draft and a fluorescent light sculpture titled Spiral Betty, a feminist totem that’s a play on minimalism and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty.

ABF: What are you reading?

JS: I mostly read contemporary fiction, but I’m currently teaching a course on graphic novels, so the past few months I’ve been re-reading a lot of graphic novels, zines, and artist books. I am reminded what a gutsy art form they are, and am awed at how the picture/text relationship in the best novels can engender such intense emotional and political narratives. Ron Rege’s Against Pain comes to mind. I just read Alison Bechdel’s new memoir Are You My Mother?, which was pretty amazing. It delves into her fraught relationship with her parents, but it’s also about reading, self-analysis, and the everyday practice of being an artist.

Amanda Beroza Friedman is Blogger-in-Residence through March 29, 2013.