In August 2013, the art blog Glass Tire posted a review of The Black Letter, a two-page treatise that had been taped to the doors of galleries in the Dallas, Texas design district. Written by an artist using the pseudonym “The N***** Bankzy,” the letter tells the reader how to produce artworks that conform to stereotypes and abject notions of blackness. Writer Darryl Ratcliff describes this written performance:

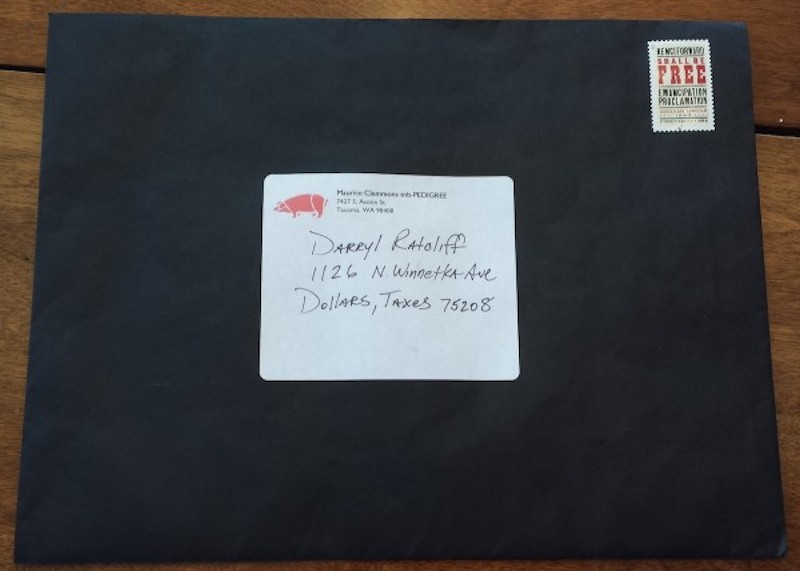

“The letter came in a black envelope, with a stamp commemorating the Emancipation Proclamation, and a custom address from one Maurice Clemmons tnb-PEDIGREE, with a red pig in the corner and a Tacoma, Washington address… The Black Letter starts off ‘Dear Culture.’ It contains a loose mission statement on page one, and a list of ten concepts for art projects on page two. The tone is aggressive, confrontational, and contains 47 words that could get you fired from your job. It is also funny, bitingly satirical, serious, misguided, and at times brilliantly clever.”

Ever since The Black Letter came to my attention I have been thinking about the artist’s frequent use of the n-word, and questioning whether satire is an effective way to dislodge racism.

It can be assumed that Bankzy created The Black Letter in response to assumptions that are often made about black artists, such as the idea that their work can only be about identity—the most dreaded of themes. Or, as Ratcliff posited, The Black Letter may be a response to the dearth of spaces in Dallas actually showing works by black artists. Bankzy’s motivations are as unclear as his intended audience. Was The Black Letter meant for gallerists and curators, particularly those who have limited views of what constitutes “black art” (if there is such a thing)? Or collectors desirous for artworks that equate the black experience with humiliation and suffering? Or was Bankzy calling out fellow artists who knowingly capitalize on black stereotypes, further entrenching them in public consciousness? This last point is particularly salient because Bankzy has done this very thing.

Kara Walker, World Exposition, 1997; cut paper on wall; installation dimensions variable; approx. 120 x 192 inches. Artwork © 1997 Kara Walker, Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Several contemporary artists have explored black identity and the abject. I am thinking specifically of Kara Walker, William Pope. L, Chris Ofili, and Robert Colescott. In, for example, Walker’s cut paper installation World Exposition (1997), she draws on stereotypes that associate black people with excrement, animals, and hypersexuality. Or there is Pope. L’s Rebuilding the Monument (1995-99)—bags of manure bearing a portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—in which the artist challenges the canonization of the slain civil rights leader. Unsurprisingly, controversy has surrounded the work of both artists. But where their works lead audiences to consider the myriad ways that blackness operates, and complicates their understanding of history, Bankzy does not. His satirical letter flattens the experience of being black into little more than incidents of degradation. And although The Black Letter draws attention to issues of race in the art world, it does not do enough to move art audiences forward and beyond complacency.

Pingback: SMU curatorial fellow Sally Frater takes issue with “The Black Letter”