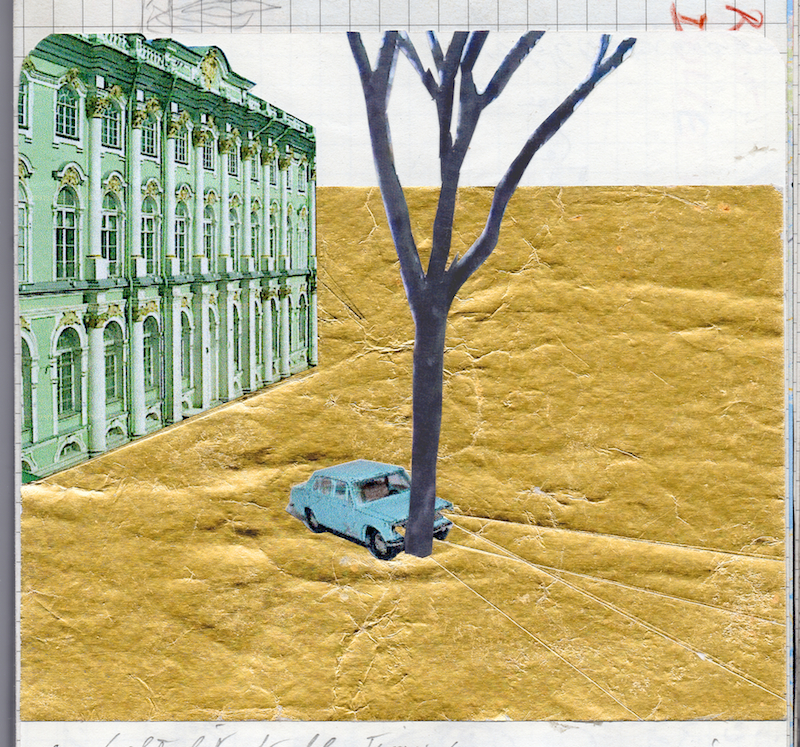

Francis Alÿs. Draft for Lada Kopeika, an ongoing project for Manifesta, 2014. Collage with gold leaf; 4.5 x 5.1 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Manifesta 10 is scheduled to open at the end of June in the State Hermitage, the largest museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Since the early stages of organizing this edition, there have been questions about the site and whether this self-described “itinerant European biennial” should even take place this year. Doubts were raised after the Saint Petersburg municipal deputy Vitaly Milonov “masterminded” an anti-LGBT bill, adding to the city’s already conservative reputation. In 2013, ultra-Orthodox activists in the city protested a Chapman Brothers exhibition at the Hermitage, and in 2012 a group calling themselves the Saint Petersburg Cossacks vandalized the Nabokov Museum in protest of Vladimir Nabokov’s work, particularly his novel Lolita.

Chto Delat. Installation view of the exhibition What Is to Be Done?—The Urgent Need to Struggle at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, 2010. The banner reads, in Russian, “We want a general strike!” Courtesy the artist.

In August 2013, the Irish curator Noel Kelly created a petition calling on Manifesta to reconsider the location of this year’s biennial:

Earlier this month, [Vladimir Putin] signed a law banning the adoption of Russian-born children to gay couples and to any couple or single parent living in any country where marriage equality exists. Last month, Mr. Putin signed a law allowing the police to arrest tourists and foreigners suspected of being gay or pro-gay and detain them for up to fourteen days. He also signed a bill classifying “homosexual” propaganda as pornography with vague wording that could subject anyone arguing for tolerance or educating children about homosexuality to arrest and fines. There is no defense for such actions, which occur against a backdrop of growing violence against gays and could be seen as a license for even more violence… It is important that we send a message to the Russian government that such draconian measures will not be tolerated. In particular, the art world community must act now and request that Manifesta is either awarded to a different city, postponed until human rights are restored, or cancelled as a sign of support for the LBGT community.

Kelly’s petition has provoked a significant response in Russia and at the time of this writing has garnered more than two thousand one hundred signatures. The official response from the founding director of Manifesta, Hedwig Fijen, addressed the fact that Manifesta has historically “chosen to operate within contested areas” and “the organization often finds itself in a place of political non-alignment.” That is, Manifesta has always taken place in a location with complicated social, economic, ethnic, or religious situations, and the location of Saint Petersburg is no different. The biennial will not move, as expressed in a statement by Kasper König, the curator of Manifesta 10.

Before the Russian annexation of Crimea in March, there was no predominant position on the ethical legitimacy of Manifesta 10, but after Putin’s anti-Western turn and confrontation with Ukraine, increasing numbers of artists and curators from Russia and Europe believe the biennial should express opposition to state policies. In a new petition that has almost nineteen hundred signatures to date, Dutch and German artists are calling for the postponement or cancellation of Manifesta 10 until Russian troops withdraw from the Ukraine. Others support Manifesta but recommend that the exhibition make a critical statement because the adoption of a neutral position by an international event of this scale would only legitimize the authoritarian regime under which the biennial will operate. The Russian artist Olga Tobreluts writes that Manifesta 10 should be dedicated to Ukraine and that the curator should invite more Ukrainian artists (now there are only two Ukrainian artist in the list: Boris Mikhailov and Alevtina Kakhidze) whereas the former Pussy Riot activist Maria Alekhina (in Russian) has suggested moving the biennial to a venue in the Ukraine. Joanna Warsza, the curator of Manifesta’s public art program, has expressed that she will take a critical approach to the sociopolitical situation and invite artists from post-Soviet countries including Georgia and Ukraine, which both have complicated relations with the Putin regime. But even this tactic is problematic because the municipal government controls and certifies public projects. The artist Paweł Althamer was slated to participate in Manifesta 10 but has withdrawn. After trying to balance their critical voice with their participation, the Russian art collective Chto Delat also withdrew, opting to instead organize their own events to confront the biennial.

Alevtina Kakhidze. A Walk with Duchamp or The Rendezvous, 2012. Performance at Arsenale, Kyiv. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Jevhen Chorny. Kakhidze, a Ukrainian artist participating in the public programs of Manifesta 10, refuses to withdraw from the biennial.

The political situation is not the only problem with Manifesta 10, which has been facetiously named (in Russian) the Exhibition of Dead People, even though the works of only nine deceased artists are included: Henri Matisse, Joseph Beuys, Juan Muňoz, Mike Kelly, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, Timur Novikov, Louise Bourgeois, and Maria Lassnig (who passed away earlier this month). The list of selected artists includes the usual suspects—that is, those artists who appear in one biennial after another—such as Francis Alÿs, Marlene Dumas, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Thomas Hirschhorn, Bruce Nauman, Boris Mikhailov, Gerhard Richter, Slavs and Tatars, and Wolfgang Tillmans. For Manifesta, a biennial exhibition that since its conception has had a reputation for showing young artists and dynamic work, this is a scandalous yet predictable transformation into one of the usual festivals. Kasper König, the Manifesta 10 curator, is used to working with famous artists and big budgets, which is good for the Venice Biennale but not for Manifesta. And the Hermitage museum, which will celebrate its 250th anniversary this year, is no better a partner for Manifesta. It’s obvious that Manifesta chose Saint Petersburg for financial reasons; Manifesta’s resources are limited, and the Hermitage can obtain funding for the biennial from the state budget. Like the novice listening to the “greed is good” speech of Gordon Gekko in the film Wall Street, Manifesta is heeding both the Hermitage and the municipal bureaucracy. Manifesta still has a chance to change the situation, but life is not a movie, and a surprising denouement is unlikely.

Pingback: Manifesta 10: A Biennial in Question - 1-954-270-7404

Pingback: traveling to saint petersburg next week - Amelia Groom