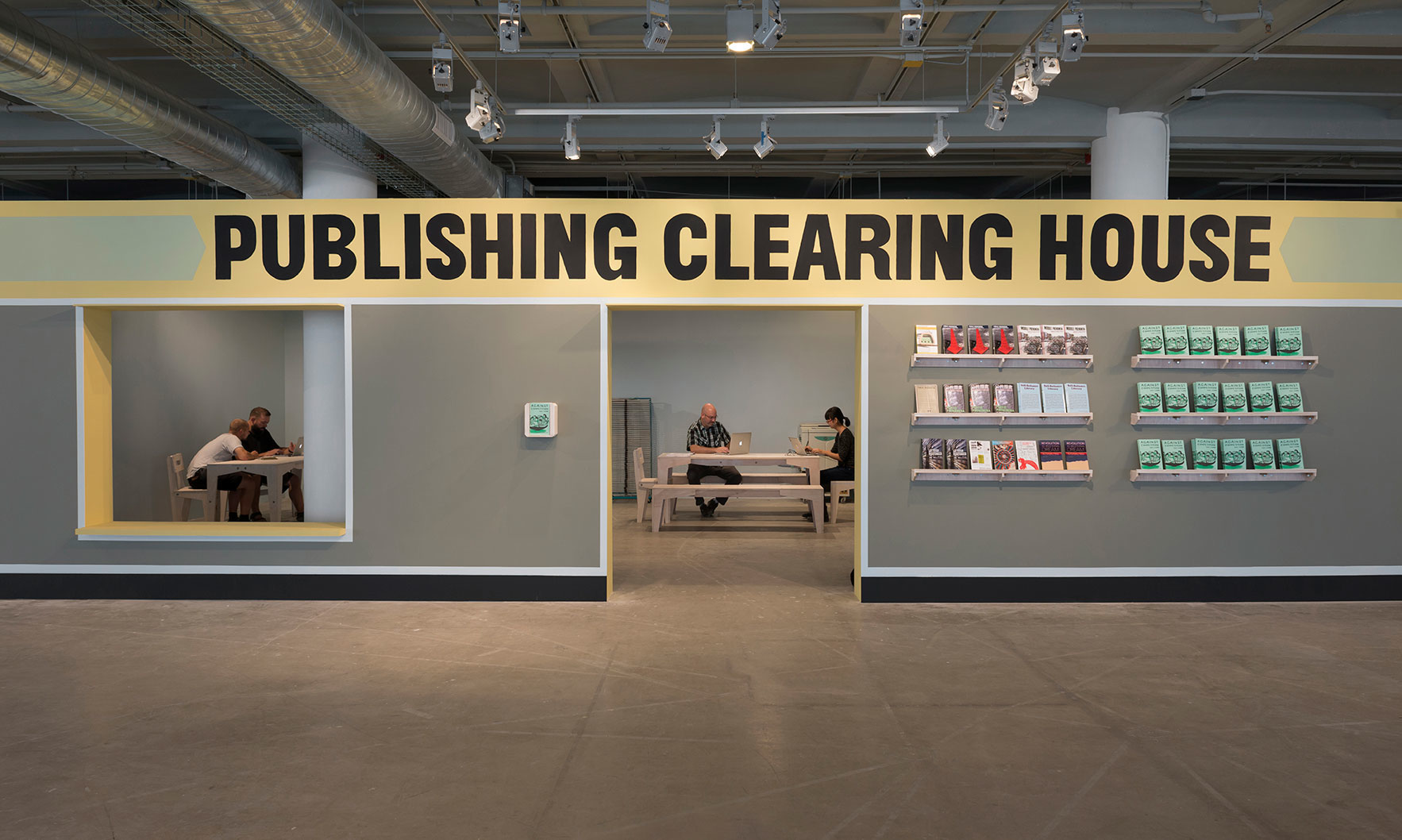

Temporary Services. Publishing Clearing House, 2014. Installation view in A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action, Sullivan Galleries, Chicago. Photo: James Prinz

When Mary Jane Jacob received a Warhol Foundation curatorial research fellowship in 2012, her task was vast: to survey Chicago’s social-practice scene. Jacobs’s project will culminate this fall, when she opens the exhibition A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action at the School of the Art Institute’s Sullivan Galleries, which she directs. The show will realize new projects by ten artists who claim Chicago as the springboard for their practice. Dan Peterman, an artist in the show, says that art in this city is “not just to represent culture but [also] to afford the possibility for culture in which art could be more of a social force.” In this interview with Rachel Craft, Jacob offers advice to artists who similarly want to affect social change through their work and how to plan—or not—the evolution of their projects.

Rachel Craft: As someone who has developed socially engaged arts initiatives for more than twenty years, how have you seen art have an impact on the future of a community?

Mary Jane Jacob: Artists being welcomed in and sought by communities is a great development. I got into this practice, overtly and determinedly, in the wake of the late 1980s culture wars spurred by the censorship controversies of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). Art in museums was not enough for me, and moreover the NEA seemed to be more about museums as corporations than about the development of art and artists. For me, the public terrain was not just an alternative but also the identity museums should have: being free and public. But if they were no longer going to be so, I thought I would try my hand in public space.

But this was an era of defending that artists had worth, value, and were intelligent, serious, and important to society. Public space brought more meaning to that point because it wasn’t a theoretical or contained exercise; it had to deal with the reality of being present in and with the public. I never really found the public—people engaged on a direct, one-to-one level—to be opposed to art and artists. The negativity came from right-wingers in Congress, and their campaign continues on all fronts today: look at the lack of gun legislation, the continued erosion of women’s heath rights. The arts were a testing ground for them. But the public—people, then and now—was open and so often gratified by exchanges and projects with artists.

So I have to say that the impact is vast, and I do not base it on the number of sculptures, or socially remedial programs, or renewed landscapes and cityscapes. Art has an impact—somewhere, somehow, each and every time—on individuals and their communities. And the acknowledgement, the openness, about that impact has changed since and because of the culture wars. People didn’t vote out art; maybe they rediscovered it.

RC: What advice do you have for artists who want to influence social change through their work but aren’t sure where to begin?

MJJ: Read less theory (and opinions of critics) and work with artists (and maybe curators) you admire: they always need help; they will always be great mentors; they will become colleagues and friends. I think you learn so much on the ground, and we can’t talk about and learn process from a book.

Also, be true to who you are. I know that sounds cliché, but what I mean is: Dig deep to remember why this direction in art, this kind of work, motivates and inspires you. Remember and value the seemingly small anecdotal experiences in life—maybe childhood, maybe yesterday—that told you something about people; remember that when you work and interact with them. Think about what your values are. No one asks you about values in school, in a grant application, in a project. But they are at the center of those endeavors. So remember your values and apply them, not someone else’s theory, to what you do.

RC: Speaking of grant applications and the more formal aspects of organizing a community project, how can artists balance a need for flexibility throughout the evolution of their project while still providing enough specifics to encourage community (and funder) support?

MJJ: I think you need to know the aim of the work—what do you hope to accomplish and why?—but I do not mean a goal of what it will look like and be. I wish funders would ask (as I think some communities do): What is your interest? How does it relate to you as a person in or out of the community or situation? How does it touch your values? What will the process be? And how is that process one of shared discovery, which will lead to an outcome but which would be wrong to predict before that process begins, grows—ebbs and flows—and finds a place to land? Process is what it is all about; that’s where the flexibility resides because that is what process can do. You are right to say evolution: a process needs to evolve, to co-evolve with others. And process is not a set of best practices that you read. You need to embody process and to live it!

RC: Some artists may hope that their projects continue to evolve, even after their direct involvement comes to an end. Do you have advice for artists who want to develop a framework for sustained engagement?

MJJ: I think sustaining an engagement can happen in many ways. I would not make that demand on a work at the outset; that can stifle the process and may be a bit hubristic—to feel it needs to continue to exist.

Of course, finding individuals who are partners—who share a mission rooted in shared values—can be one way; they can continue the engagement. I saw this happen with a work in the “Culture in Action” program I curated in the early ’90s: Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s project Tele-Vecindario led to the organization called Street-Level Youth Media, which is still around, twenty years later. Had we started with the goal to establish that organization, the project would not have lived, discoveries would not have been made, and we’d have gotten stuck in administrative questions.

I have also seen artists’ work that has nothing initially to show has later been sustained because the reality of the place, situation, and community has really changed in the process. So those projects haven’t ended either. So my advice would be to be open to what might happen, but see what happens first.

RC: Have community priorities and needs changed since your earlier projects, and do you foresee new areas of focus in the future?

MJJ: Sadly, in society we still are dealing with the same concerns: education, immigration, housing…and these are the same as a hundred years ago, too.

My personal focus now includes thinking about art in a wider frame than social practice. This leads me from art objects to art therapy, especially as it is taught as a progressive practice here at the School of the Art Institute, where I work.

So I think social practice has given us a chance to believe more generally in art and in artists in our own community. But not every institution of art practices with the value of engaging a wider spectrum of people. It’s not where galleries are coming from, or auction houses, or art fairs. Maybe it’s okay that they are different, but that commercial aspect carries over into museums. So there’s still a lot of elitism. But organizations, artists, curators, and art that can transgress this sense of high and low—that’s the key.

A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action will be on view at the Sullivan Galleries of the School of the Art Institute, September 20–December 20, 2014. Concurrently, Mary Jane Jacob has organized the Chicago Social Practice History series, four guest-edited volumes that include nearly one hundred chapters and one hundred fifty voices, and “A Lived Practice,” a symposium to be held November 6–8, 2014, that will encourage further discourse of social practice.

Pingback: Planning Social Practice: An Interview with Mary Jane Jacob - 1-954-270-7404