Guerrilla Girls, 2015.

Sitting outside the Department Head’s office at Minneapolis College of Art & Design I was nervous, clearly unaccustomed to sounds and vibes of academia. I felt like an imposter. For more than two decades I had worked in the field as a curator, writer, and art administrator. Somehow by the time I left the building I had agreed to teach a course in Gender, Art & Society and help plan a Guerrilla Girls project for MCAD.

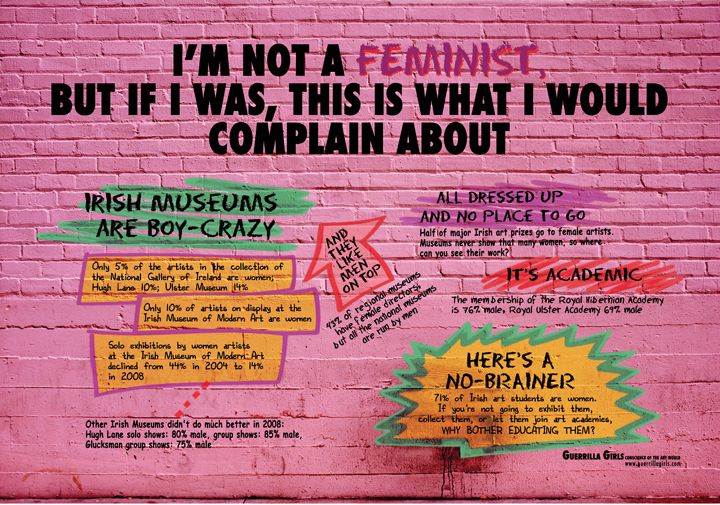

In a way it was a bit familiar. From 2008 to 2009, I had organized an all-Ireland Guerrilla Girls project. The newly commissioned work—and the statistics that backed up the research—confirmed what we knew about sexism in Ireland while also providing a space for discussion about the state of women in the arts. We also observed the role of artistic collectives, the power of art activism, how process was as important as the end result (the art object), and the role that feminist art methodologies played (and plays) in what we understand as contemporary practice today. These ideas—the power of socially engaged art, the history and legacy of feminist tactics and methods of making art, and the collective consciousness found in art activism—all were at the core of every Guerrilla Girls project I’d worked on: the Girls in Ireland, teaching at MCAD, and what would become the Guerrilla Girls Takeover, happening across Minnesota from now until March. The process for organizing the Takeover was intentionally non-hierarchical and inclusive—aiming to bring three big museums together while also allowing for grassroots participation. The methodology of prioritizing process eventually became a core principle for the Guerrilla Girls project in the Twin Cities. Lead by an adventurous steering committee representing a wide range of cultural institutions and independent curatorial voices, our aim is to open up political and dialogical space to answer questions like:

- What does or will the Fourth Wave of Feminism look like?

- How can collective action and art activism impact the political consciousness today, especially with young people?

- How can we utilize the history, integrity and energy of the Guerrilla Girls to attempt to answer these questions?

Guerrilla Girls. I’m Not A Feminist, 2010. © Guerrilla Girls.

I first heard of the Guerrilla Girls while studying art history at the University of Minnesota in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The group served as a beacon of intelligent, socially engaged political art that spoke to a broad layer of young women (and men) dedicating their lives to art. Importantly, the activist art movement included artists and others who were engaging in an art practice that “had something to say.” Some of the exhibitions in Minneapolis that I worked on as a tour guide and intern during this time included artists Carrie Mae Weams, Lorna Simpson, political posters from the former USSR, Helio Oiticica, and Jacob Lawrence. Artists such as Jenny Holzer and Magdalena Abakanowicz were commissioned to create sculptures for the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, and I researched them for the first audio guide at Walker Art Center. Frank Gehry built his first museum, the Weisman Art Museum, encouraging us all to see and think differently about art and architecture. Griselda Pollock was a visiting scholar at UofM, and many of us studied with her, where she not only expanded our knowledge of feminist art criticism, but also encouraged activism in our academic pursuits. There were also several gigs by the punk group the Riot Grrls at First Avenue, where music, art and politics collided every weekend. For those of us who were studying art and art history and volunteering and working in local museums and galleries, the Guerrilla Girls and artists like those mentioned above encouraged activism in the spaces where we believed meaning, value and understanding was being constructed—in art practice, universities and museums. We saw art as a way of creating meaningful dialogue, and it had the capacity to reflect and influence thinking in society. We believed that activism in art was essential. This time was decisive (not seminal…the Girls discourage that word…) in my curatorial practice.

Twenty-five years later we now are at a point when the ideas embodied in feminism are at once institutionalized and co-opted by the art establishment, and yet are more important than ever. For more than three decades the Guerrilla Girls have served as agents of provocation, using humor to push boundaries and pose demonstrative facts and figures that challenge the patriarchal, hetero-centric [art] world. Yet how does the Guerrilla Girls’ process-led practice of a collective, statistic-driven and advertising-orientated aesthetic work within a post-Feminist context? Well, it’s complicated; and in a way the artwork doesn’t work because it’s not about the art—it’s about the dialogical process; it’s about awareness and change. And the collaborative process is hard, uncontrollable, fraught with angst, and—for those of us that embrace it—highly impactful. We know that the notion of a non-binary spectrum of complicated definitions of gender is part of the context of living and creating in 2016. My MCAD students taught me that. I wonder, though, if we/they understand how we got here? Does the Millennial generation, one particularly concerned with transgender issues that question the language and motivations of the Guerrilla Girls, understand that they sit on the socio-political space that activists like the Girls and others fought for? We are not a post-racial or post-feminist world. Yes, important changes have been made and gains have been won, but we are far from equality. Yet shockingly, we seem to be even farther from the intelligent, dialogical critiques necessary to move beyond a 60-letter retort or an internet troll comment. A click-and-go-pseudo-dialogue without consequences, accountability or integrity has now seemed to replace the “normal” way of dialoguing about art. But I expect more; I expect intelligent debate with progressive arguments that push the boundaries of understanding and ideas.

Guerrilla Girls. Toast to Irish Art, Lads (Pssst: Not So Fast, Lasses), 2010. © Guerrilla Girls.

When I first heard about the critiques of the Guerrilla Girls in Minneapolis in 2015, I was excited; ecstatic in fact. This was just what we wanted—dialogical space to continue to push the boundaries of the discussion. The project was never to make the Guerrilla Girls a spectacle or artist-genius (it’s hard to even write that phrase it’s so ridiculous). The project, again, was to talk about what kind of feminism was needed today. In Ireland we often heard: “I’m not a feminist, but if I was this is what I would complain about.”

The answer? We are still waiting for more dialogue; we will get that in the next few months. It has begun and some the answers will come. Yes, it’s that simple but it is also not that easy. What we do have are hundreds, if not thousands, of people and more than thirty groups, organizations, and institutions who have emphatically and energetically joined in the Guerrilla Girls Twin Cities Takeover. We will examine these questions and debate and argue – and then reflect. Do you need more proof that the feminism prophesied by the Girls is still needed? Still wanted? Ask us at the end of March… we might know more then.

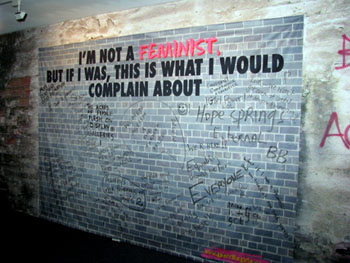

Collaborative wall open to visitor additions at the Guerrilla Girls’ Project Ireland, 2009. Photo by Dermot Burns.

Formed in 1985, the Guerrilla Girls were influenced by the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s in the US, and were a part of the opposition to the backlash against the Feminist movement and, later, central to the dialogue responding to issues in post-Feminism and art. The Guerrilla Girls explore subjects like politics, film, and popular culture, feminism and fashion, and the attempt to achieve sexual and racial equality, calling themselves the ‘Conscience of the art world.’ They wear gorilla masks in public to conceal their identities, and place the focus on issues rather than personalities, working collectively and anonymously to produce posters, films, billboards, public actions, books and other projects.

Pingback: Art & Pancakes, January 31st, 2016 | Bay Area Art Grind

Pingback: 30 jaar Guerrilla Girls – Mieke van Os