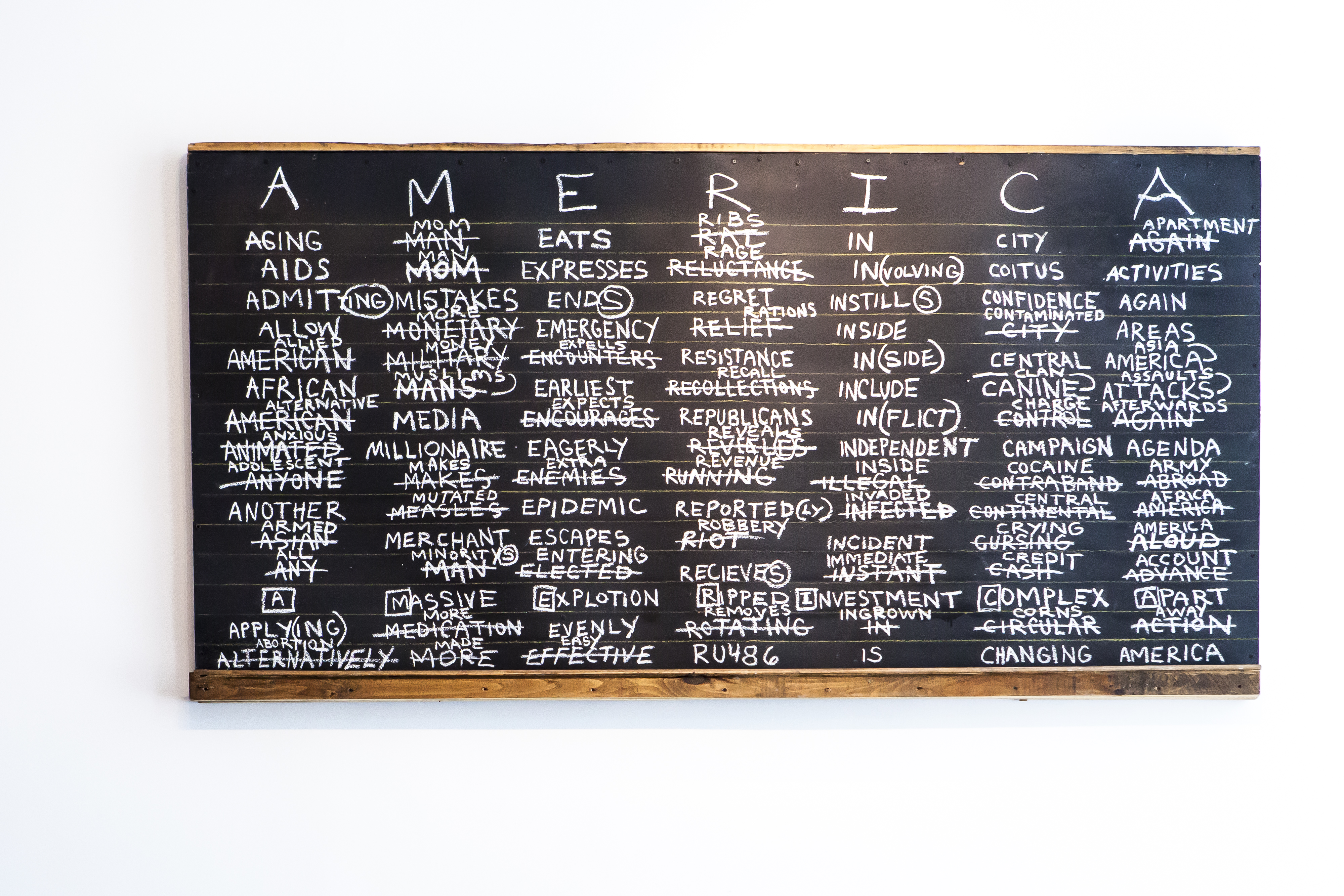

Installation view of Art AIDS America, Bronx Museum. Willie Cole. How Do You Spell America? #2, 1993. Oil stick, chalk, wood and latex on Masonite, 49.2 x 96.5 x 4.5 inches. © Marisol Díaz, 2016.

A few months ago, Suzanne Moore wrote, “A generation of artists were wiped out by AIDS and we barely talk about it.” The sentiment rang painfully true for me, a gay man who lives in New York and spends my days looking at and thinking about art. But it also left me with heavy questions: How do we start this conversation? How do we keep alive the memory of all those untold thousands lost to AIDS? And how do we talk about it in a way that acknowledges the crisis is far from over and, in some parts of the world, has never been worse? Two excellent, challenging summer exhibitions—Art AIDS America at the Bronx Museum of the Arts and Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)—give this conversation the initiating jolt it needs.

Organized in partnership with the Tacoma Art Museum, Art AIDS America offers a broad survey of artists who grappled with the AIDS crisis, including a large number who died from it and many more who knew them well. Variously documentary, abstract, and propagandistic, the works haven’t lost much of their urgency, and together they reveal a community that harnessed the power of art to tell untold stories and to fight, even in small ways, for the dignity, exposure, and basic services it was denied. Just as crucially, they stand as a holistic-yet-fractured document of a moment generally defined by images of lesioned young bodies, wasting away and otherwise lost to history.

Installation view of Art AIDS America. Right: Izhar Patkin. Unveiling of a Modern Chastity, 1981. Rubber, latex, and ink on canvas. © Marisol Díaz, 2016.

Artworks by the usual suspects like David Wojnarowicz, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres are all included, but some of the more abstract works caught me off guard and left a haunting, more lasting impression. Izhar Patkin’s Unveiling of a Modern Chastity, the earliest work in the exhibition, was made as the first gay men were coming down with the then-unknown illness; it’s a sickly yellow painting, shot through with oozy, rust-colored wounds. Ross Bleckner’s massive, detailed painting Brain Rust evokes a foggy scan of a brain, weakened by the ravages of HIV or the experimental medicines used to treat it. Tony Feher’s lovely hanging chain of empty green bottles, Green Window, takes on a sadder, more poignant tone in the wake of his recent death after decades of living with the virus.

It’s no secret that mainstream LGBT history—if such a thing even exists—is usually a case study in whitewashing. The exhibition does little to buck this erasure, but its inclusion of works by a handful artists of color is at least a gesture toward involving black and Latinx artists in a critical, institutional conversation from which they’ve traditionally been excluded. Understated contributions from Bronx natives Glenn Ligon and Whitfield Lovell, as well as a neurotic, impressionistic chalkboard piece by Newark-born Willie Cole that soars over the lobby, infuse the exhibition with a racial consciousness, suggesting the ways that systemic racism intensified and continues to amplify the epidemic for certain populations. A suite of wonderful self-portraits by the young Kia Labeija, the only female HIV-positive artist of color featured in the show, brings us into the present moment.

Installation view of Art AIDS America. Center: Tony Feher. Green Window, 2001. Plastic bottles with plastic caps, chain, wire, water, rope, dimensions variable. © Marisol Díaz, 2016.

Inside the white cubes of MoMA, the raw, unfiltered grit of Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is all the more audacious. Described by the museum as a “downtown opera,” the slideshow with a soundtrack gained a cult status in 1980s New York, thanks to Goldin’s frequent improvisational presentations of the work at theaters and bars around the city. The looping photographs document Goldin’s circle of friends and lovers in their shared pursuit of intimacy, showing them having sex, dancing in clubs, recovering from domestic abuse, shooting up drugs, and dying from AIDS. The images are joyous and tragic, uncomfortable for how confrontational they are and compelling for the same reason.

This showcase of Goldin’s subjective and urgently confessional work is a timely rebuttal to the major Robert Mapplethorpe retrospectives mounted earlier this year at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the J. Paul Getty Museum. Where Mapplethorpe’s photographs are perfectly composed and focused, Goldin’s are crooked, cropped, and blurry. Where Mapplethorpe’s subjects, whether flowers or nude black men, seem like nothing more than aesthetic objects, the emotional and physical intimacy of Goldin with her subjects is almost overwhelming. It makes for a fascinating contrast to think that both bodies of work emerged from the same milieu and the same time. We need not rank the merits of either artist, but with Goldin’s pitch-perfect soundtrack and original 35 mm slide format, the revelations of Ballad seem as fresh today as they must have thirty years ago. The work transports you to a community of people whose lives, even as they were ravaged by drugs and AIDS, were rich with love and desire.

Nan Goldin. Trixie on the Cot, New York City. 1979. Silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8″ (39.4 x 58.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Marian and James H. Cohen in memory of their son Michael Harrison Cohen. © Nan Goldin, 2016.

Although the exhibitions address the AIDS crisis from markedly different points of view—the Bronx Museum’s broad, direct, and relatively inclusive, MoMA’s intimate, oblique, and subjective—each makes a pressing case for art’s relevance during times where confidence in politics, government, and the goodness of humanity are in short supply. Through their work, these artists created space to expose and make sense of the ravages of AIDS, apart from a world that didn’t acknowledge the problem for years. Their art allowed for the coexistence, however uneasy, of hope, criticality, ambivalence, and deeply felt emotion. It held the world accountable at the moment and created a record for posterity. Although no exhibition can fully account for the destruction AIDS wrought on artistic communities and the world at large, these two shows succeed as conversation starters.

Nan Goldin. Philippe H. and Suzanne Kissing at Euthanasia, New York City. 1981. Silver dye bleach print, printed 2008, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8″ (39.4 x 58.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. © Nan Goldin, 2016.

Art AIDS America is on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts through October 23, 2016.

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is on view at MoMA through February 12, 2017.