Made by students Nick Ward, Andy Braunschweig, and Grant Johnson, Surveillance, 2013. Foam poster board, color printer ink, paper, glue. Student work generated in an eighth grade English class as part of a unit on dystopia.

There’s a lot of talk these days about the dismal state of the American educational system, “the crisis in education.” Mandates for more tests, and thus more teaching geared toward those tests, go hand-in-hand with shrinking budgets, increasing class sizes, and widening achievement gaps between students rich and poor, white and brown. A revolution is needed and, in my mind, contemporary art and artists are essential to it.

Revolutionizing education means sizing up this broken and inequitable system and radically rethinking how we raise future generations. In the words of Carl Andersen, an Art21 Educator and a middle-school English teacher in Minneapolis, Minnesota:

Public school teaching is saddled with a messy situation due to the current political dialogue. There is tremendous pressure to keep standardized test scores improving at all costs—that is unfortunately the bottom line—and it is draining the life out of classrooms. Authentic learning and cultivation of the creative process is being sacrificed at this altar.

Education is a field in vital need of innovative thinking. Here is where contemporary artists come in: Artists can play a fundamental role in helping us reimagine the possibilities for education; they give us new ways of seeing and thinking about ourselves, our relationship to the world around us, and how we participate in daily life. Artists today work across disciplines to deal with urgent (as well as timeless) concerns in ways that support the skills an education should ideally instill: original and critical thinking, problem solving, self-expression, innovation, collaboration, creativity, compassion, empathy, risk taking, discipline, and curiosity. Art is more than an aesthetic or sublime experience: it is central to what makes us human and allows us to share ideas, aspirations, and questions. In the end, it is how we progress in our thinking and humanity.

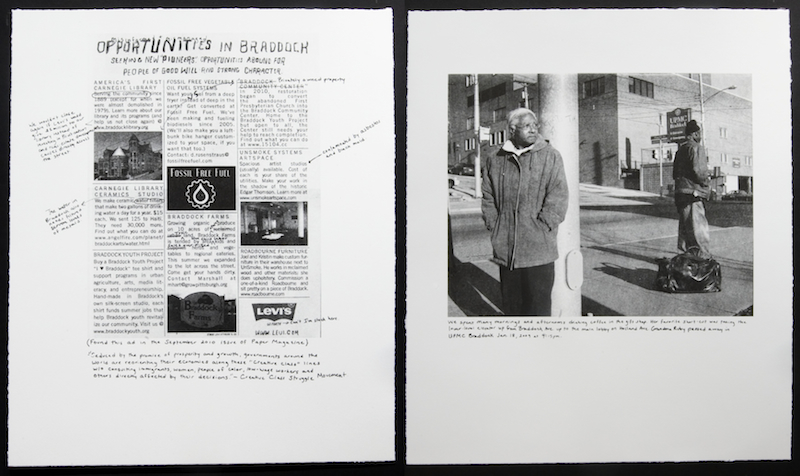

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital) details, 2011. Portfolio of 11 prints; photolithographs and silkscreen on Stonehenge 250 gsm paper, 17 x 14 inches each. Printed with Rob Swainston, Prints of Darkness. Funded by Art Matters. © LaToya Ruby Frazier

It won’t be the artists who lead the revolution in education. I believe it will be the teachers who rise up against the unsustainable educational climate of standardization and seize the motivations and methods of artists. By empowering students with new tools and new ways of thinking, they will nurture active citizens who can care for this world and for each other. But this will be a “slow revolution,” to quote the artist LaToya Ruby Frazier.[1] While Frazier’s photographs speak to issues of environmental, racial, and economic injustice (particularly in her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania), the images themselves won’t change the systems they represent and critique. It is her work as an artist and the long-term commitment she has made to enact a form of slow advocacy that will inspire others and foment change. While each individual teacher makes a difference every single day, it is only through the sustained and collective effort of those invested in reimagining the educational paradigm that change will happen.

This past spring, I saw the seeds of this revolution in Carl Andersen’s eighth-grade English class. Every year, Andersen facilitates comparative-literature circles and uses a theme to engage students in works of fiction. This year, the topic was dystopia. Andersen and his students explored how different forms of power, authority, and surveillance impact human experience. Students studied the work of the Art21-featured artists Doris Salcedo, Do-Ho Suh, and Ai Weiwei in conjunction with three novels: 1984 by George Orwell, Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, and Waiting for the Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee.

At the close of the term, students were asked to consider life’s fragility and the dehumanizing aspects of living under a totalitarian system, based on the novels they had read, the contemporary artists they had studied, and their understanding of the geopolitical state of the world today. Students were asked to think like artists and authors, as critical thinkers and citizens of the world. In their images and videos, students synthesized complex ideas about dystopia—utilizing visual metaphors, symbolism, music, drama, and animation—connecting abstract concepts to specific literary themes, artistic concerns, and contemporary world events. Andersen and his students are germinating the seeds of the revolution.

Until we reprioritize the goals of education and the role of the arts to support teaching and learning across the disciplines, we will be saddled with the dismal reality of students who have been taught to regurgitate answers rather than think, students who don’t know how to research or investigate a question, or participate in discussion or debate, but can color in the correct bubble. If our goal is to empower the next generation of thinkers, then we need to cultivate minds that are prepared to think creatively and critically about the world and their places in it. The revolution I am imagining requires all of us invested in education to contribute: to enact a slow advocacy as individuals and a community of visionaries, and to call on artists to serve as creative role models.

_____________

[1] From a Q&A session with Frazier, conducted in July 2013 as part of the Art21 Educators summer institute, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY.

Pingback: Letter from the Editor | Art21 Magazine

Pingback: The Revolution: On K–12 Education | Art21 Magazine » DIGITAL QUIPU

Pingback: Reflecting on the National Art Education Association’s Annual Conference | Art21 Magazine

Pingback: Revamping Art Education for the Twenty-First Century | ART21 Magazine

Pingback: Artel